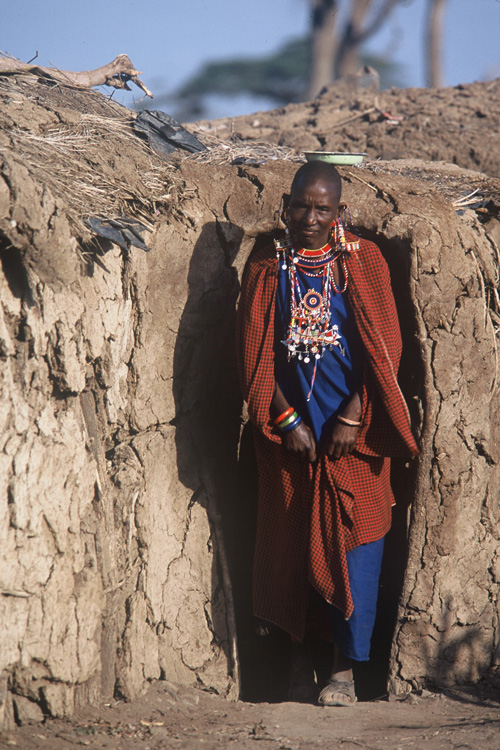

The Loliondo Game Controlled Area (LGCA), one of Tanzania’s most well-known Maasai community concessions and wildlife destinations is in the spotlight as local stakeholders and outside financial interests clash over its natural resources.

These tensions are not new, and given the location of Loliondo and the bounty of wildlife and grazing it carries, such tussles over competing land-use options are not surprising – what is surprising though is the manner in which the Tanzanian government has chosen to deal with the crisis. By choosing to side with a notorious foreign hunting company over a local Maasai community, they have shown a blatant disregard for traditional land-use rights and exposed the contradictions in their stated conservation goals.

Lying adjacent to the north-eastern portion of the Serengeti National Park, the significant array of wildlife found in this 4 000sqkm concession has over the last two decades attracted increasing numbers of hunters and ecotourists. The current dispute involves a United Arab Emirates (UAE) based hunting company called Ortello Business Corporation (OBC) with strong links to the royal family and military leaders of this tiny Arab state – they want their own private hunting grounds within Loliondo.

But tourism is a very recent arrival to these verdant ancestral lands of the Maasai who have been living and grazing cattle here for the past 200 years or so. More recently, this historical tenure was formalized in a 1959 compensatory agreement when the Maasai were moved here for permanent settlement after being banished from the Serengeti when it was declared a national park. Back in 1993 when OBC first muscled its way into Loliondo, Tanzania had just emerged from decades of heavy socialism that brought state control to every aspect of life. Quick to take advantage of the transition, the Arabs approached the then government and in the negotiations the Maasai were never consulted in any way over the granting of a long term lease. By all accounts this came as a Presidential decree offering extremely favourable terms to the new leaseholder.

Without consent or any form of buy-in from the traditional landowners, this was always going to be an acrimonious relationship. And the Arabs case has not being helped by allegations of illegal and unethical hunting practices, including the use of aircraft and machine-guns as well as baiting wildlife from the nearby Serengeti. Other accusations against them include the theft of wildlife from the concession, acts of intimidation and threats and bribes paid to silence people from within the community and government. This has all led to numerous public clashes between community residents and OBC and the authorities, who the Maasai accuse of being in cohorts with each other.

While the official government line for dealing with the disputes at this moment revolves around securing wildlife corridors in Loliondo, the inside view is that the Arabs are looking for new and better hunting grounds as they have pretty much blighted what they had. And it would seem they may just get their way again. In a recent announcement, the Minister of Natural Resources and Tourism proposed that Loliondo be split into two sections – 2 500sqkms for the Maasai and a 1 500sqkm ‘wildlife corridor’ to be reclaimed as the Minister put it “for the benefit of the nation.” With this move however, government has in essence served the Maasai with an eviction order by expropriating almost one-third of their ancestral land, and in the process made provision for the Arabs to get a new lease on an exclusive hunting bloc running alongside the Serengeti.

The issue here is not about refuting the Minister’s wish to protect the country’s wildlife – all would agree this is imperative. Rather, it’s about the continuation of policies that entrench historical land injustices and a mindset that cannot accept the ownership, empowerment and conservation credentials of traditional communities living on the edges of Africa’s protected areas. The marginalization began with the arrival of colonial powers and the dispossession and impoverishment processes were completed during the creation of the continents national parks and reserves. Post-independence governments inherited the mess, but barring a few notable exceptions, they have only served to compound the injustices.

And the great irony here is that ‘for the benefit of the nation’ may actually mean for the benefit of a few wealthy foreign hunters with an appalling conservation record – and this will come at the expense of Tanzanian citizens that have historical rights to Loliondo and a belief system and pastoralist lifestyle in keeping with being natural conservators of wildlife.

This decision points to one of three scenarios. 1) The Tanzanian government simply has no regard for the traditional land rights of their citizens, 2) They again have failed to understand the dynamics and direct links between alienated and impoverished rural communities and many of the conservation battles taking place in and around protected areas or, 3) Both of the above are correct and this has led to high-level politicians believing the financial takings on offer are acceptable. It’s a decision that must be questioned at every level.

This battle is far from over. As a local Maasai councillor has said, “We are not ready to surrender even one meter of our land to investors for whatever reasons.”

If you would like to support the Maasai sign the petition Stand with the Maasai

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()