Elephant feeding patterns are preventing fan palms (Hyphaene petersiana) from reaching full size and reproductive potential, says a new study.

Many plant species that are subject to elephant feeding are capable of resprouting, which makes evaluating the effects of elephant feeding more difficult because, while the height of plants may be reduced, they will still be present, often in high densities. While previous studies into the impact of elephant feeding have focussed on the presence, height or stem density of savanna plants, the authors of this study suggest that it is also essential to evaluate the reproductive condition of plants.

The management of elephant numbers in the Kruger National Park in South Africa, where the population has demonstrated a consistent increase in the last two decades, is a controversial subject. High numbers of elephants can result in the widespread conversion of woodlands to grasslands. Some species of plants, such as the baobab (Adansonia digitata) and several Acacia species are intolerant of consistent elephant feeding. Yet, other plant species rely on the presence of elephants for seed dispersal. The tolerance of many savanna plants in the face of elephant disturbance and their capacity to resprout from the base, stem or roots further complicates the debate, as conservation managers work to determine what constitutes ideal savanna vegetation. As a result, determining the carrying capacity of the KNP for elephants is extremely complex.

The researchers, in this case, chose to focus on the H. petersiana palm species because they are both browsed by elephants and their seeds are dispersed in this manner. The plant demonstrates prolific production of new stems in response to feeding damage and was previously believed to be resistant to elephant feeding damage because the stem densities of browsed plants were wider than those protected from elephant herbivory.

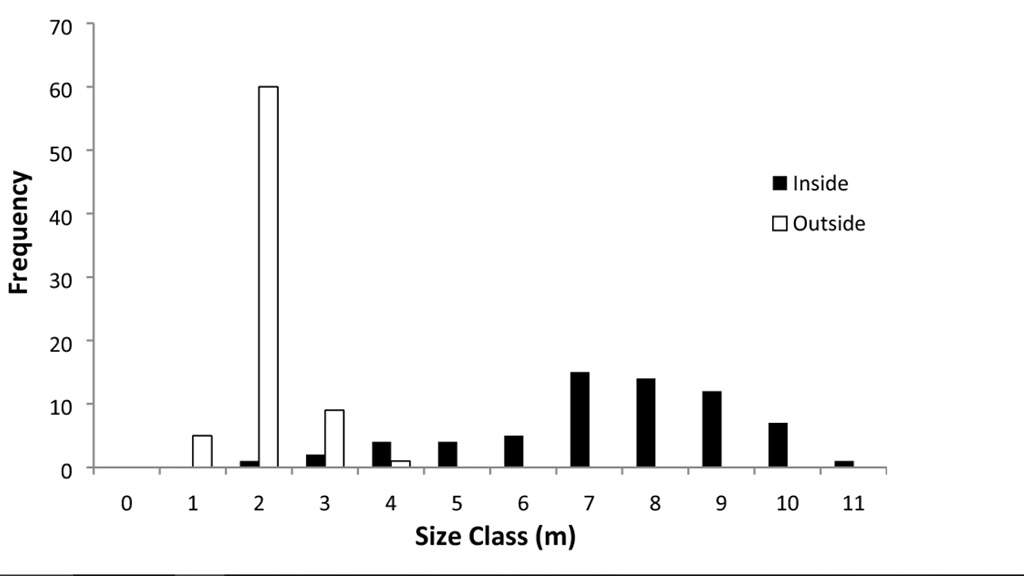

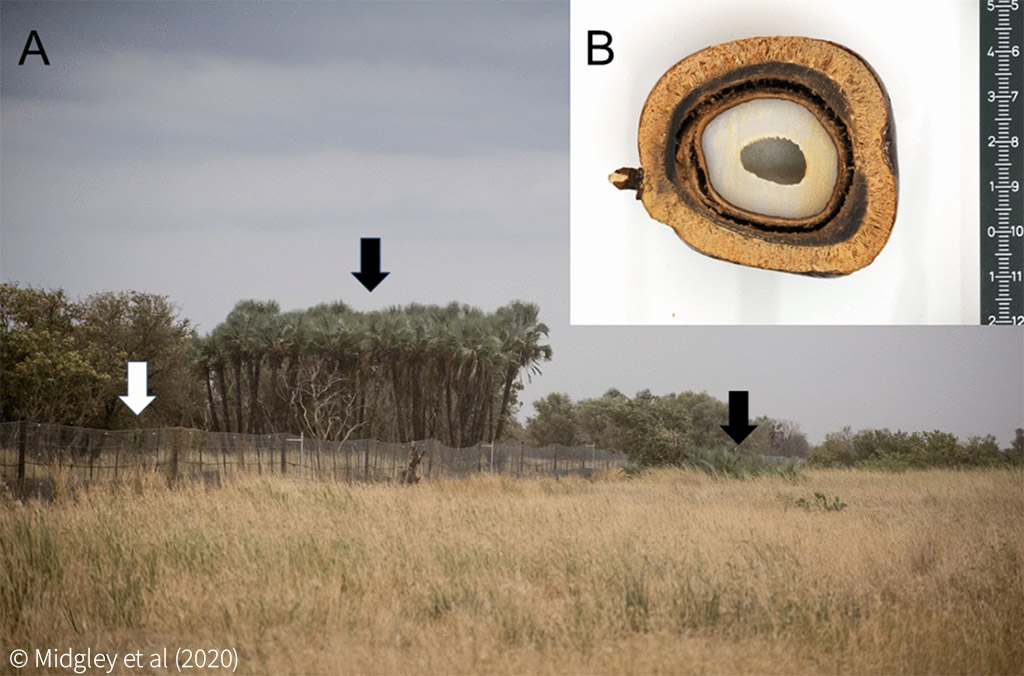

However, most plants need to reach a minimum size to be able to reproduce. Researchers compared palms within the Nwaxitshumbe enclosure (one of the rare antelope breeding camps where the plants have been protected from elephant feeding for several decades) with palm trees outside the enclosure, which had evidence of extensive elephant feeding damage. Of the 65 trees in the enclosure, 92% had reached maturity at heights of between 4-5.3m. In contrast, of the 75 palms surveyed outside the enclosure, not one had reached the necessary height for reproductive maturity, with most being over 2.5m short of the minimum. No seedlings were found either within or outside the enclosure. Outside the enclosure, this can be explained by the lack of reproductively mature trees. In contrast, the lack of seedlings inside the enclosure can be explained by the absence of elephants to aid in the dispersal and germination of the seeds.

The researchers point to three significant impacts of this mass sterilization. The first is that sterile plants cannot disperse seeds to shift their distribution range with moving climate zones, which is particularly serious in the face of climate change. The second is that without new young plants, the plant will eventually go extinct (though this particular palm species can live for over a century). The final concern is that the fact that immature plants do not produce flowers or fruits could have biodiversity implications for several animals such as vervet monkeys and pompilid wasps. The palm swifts were observed to be nesting only within the tall palms in the enclosure.

While acknowledging that their findings were limited to one plant species in one location, the authors believe that this consequence of elephant feeding is likely to be widespread and affecting other woody tree species, a conclusion supported by an extensive Google Earth survey. A previous study which compared the palms inside the same enclosure to those outside missed this negative impact on reproductive status, and the authors of the present study suggest that this is because reproductive condition is not part of a routine assessment of the impacts of herbivory. As such, they suggest that managers need to consider this impact when evaluating the impact of elephant feeding patterns, even in species that appear prima facie to be unaffected or which increases in stem density. Due to the loss of their reproductive capacity, the authors describe these palms as “the living dead” of the Kruger National Park.![]()

The full report can be accessed here: “Mass sterilization of a common palm species by elephants in Kruger National Park, South Africa“, Midgley, J., Coetzee, B., Tye, D., and Kruger, L., (2020), Scientific Reports

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()