AN ANALYSIS OF THE LION BREEDING INDUSTRY IN SOUTH AFRICA

A wild lion is a scrappy thing. A fierce, dishevelled, fly-bitten beast with battle scars from nose to tail and a matted, grimy mane. This is a rug you don’t want on your living room floor. But the beast has been cleaned up and rebranded in one of the greatest wildlife marketing stunts ever.

Since humans painted them on a cave wall in France 30,000 years ago, lions have populated our imagination. Despite being extinct in Britain and Europe for thousands of years, they have grown in stature through myths and legends.

Tens of centuries ago, kings and conquerors of Britain and Europe adopted the mighty lion as their symbol on military shields, tunics and crests, a form of marketing if you will: Look on us in awe. Use of the symbol eventually extended to the nobility, who displayed lions “rampant” and fierce, often human-like, clutching axes and swords or wearing crowns.

This adulation – or should we say, lionisation – wasn’t unique to Europe. Though not native to China, lions were given to emperors as gifts and sometimes imported via the silk road as far back as 200 BC. Those few lions left such an impression on the Chinese that they are now part of their iconography and pageantry. Lion statues abound, and the famous Lion Dance imitates the beast as a symbol of power, wisdom and good fortune.

Today, we see them on national and institutional coats of arms, sporting emblems, company logos, clothing brands and family crests – even the ignoble ones. If there is one creature we aspire to, it is the lion, king of all creatures.

Of course, identifying with the king is no guarantee of prowess. But the aspiration is there, and in our minds, the king has remained indomitable until now.

Middle: Richard the Lionheart (King of England 1189-99) carrying a shield emblazoned with the three lions that make up the royal arms of England. Illustrated by N.C.Wyeth.

Bottom left: Chinese New Year Lion Dance. ©Bob Jagendorf

Bottom right: A Chinese lion statue, Forbidden City, Beijing. ©CEphoto, Uwe Aranas / CC-BY-SA-3.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)

In South Africa, a thriving industry makes it affordable to blow a lion to kingdom come. According to Campaign Against Canned Hunting, there are about 160 lion breeders in South Africa, many of whom supply lions to hunting operators or facilitate hunts on their own land. Various estimates put the number of captive lions anywhere between 6,000 and 8,000(2)(4). That’s more than double the number of lions in the South African wild, estimated at 2,743.

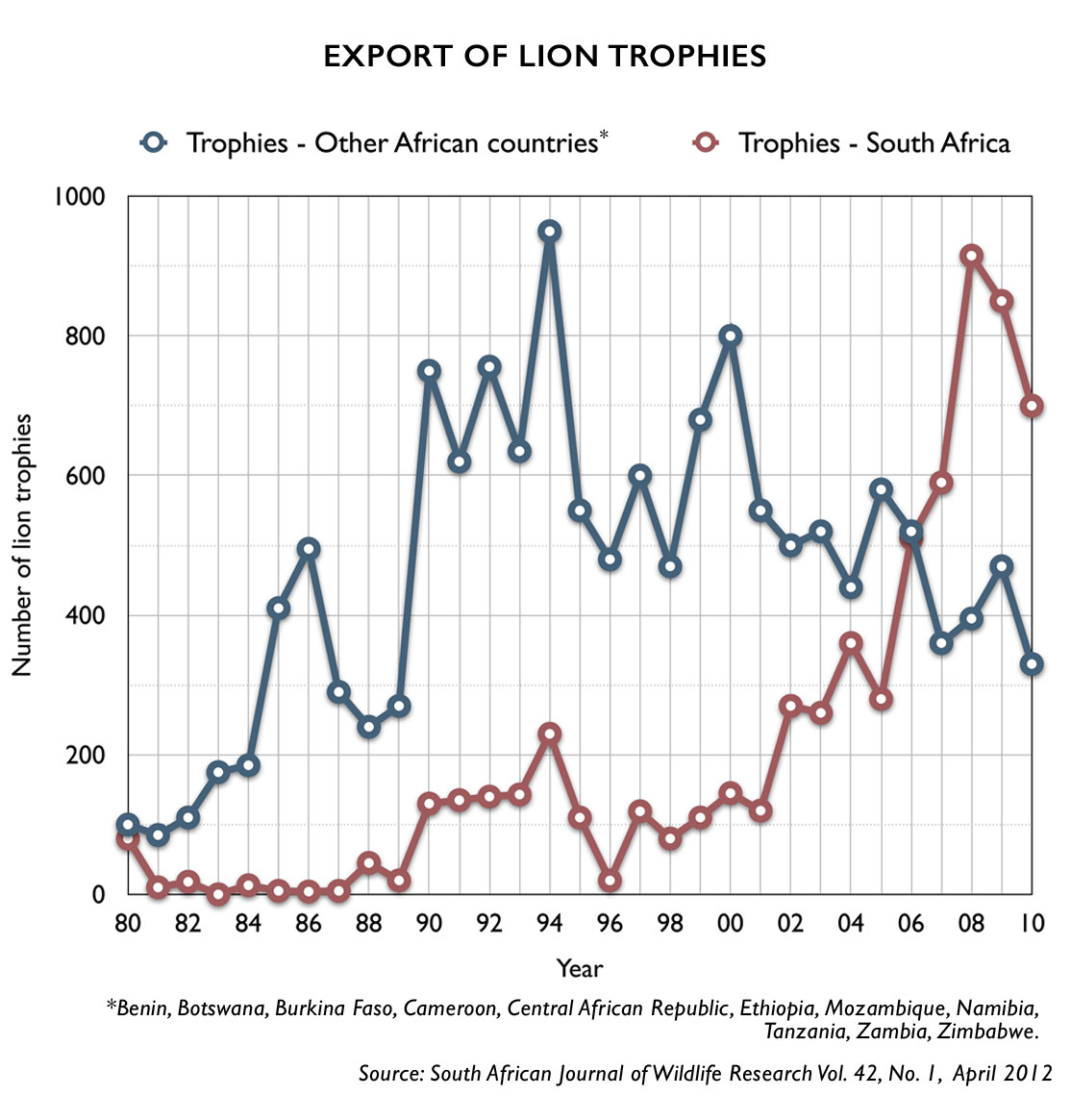

There are between 23,000 and 39,000 wild African lions left on the entire continent(1). So, using the most conservative estimates, captive-bred lions would make up one-fifth of the African lion population. Breeding lions for hunting is good business. And it’s getting better. 4062 lion trophies (more than South Africa’s wild population) were exported from South Africa between 2007 and 2011, compared to 1830 trophies between 2002 and 2006.

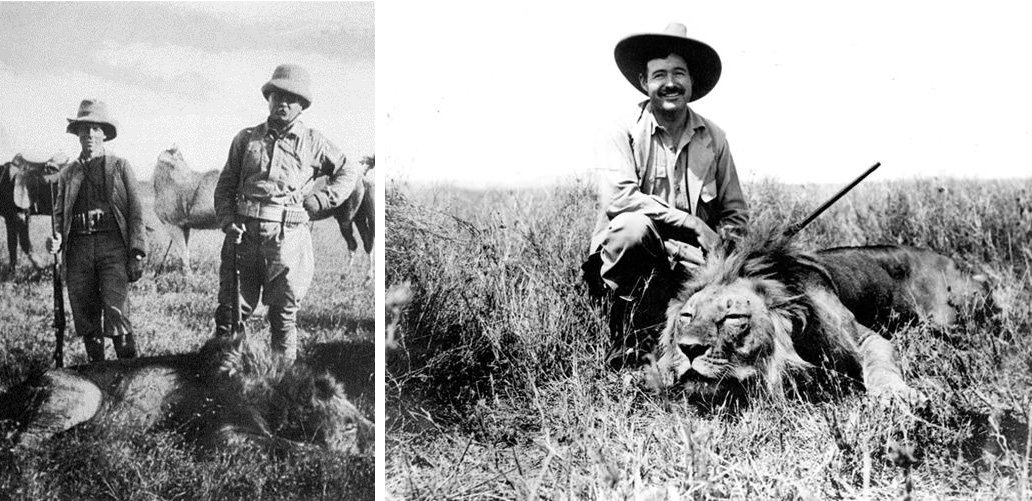

The USA is by far the largest market for trophies. The key drivers seem to be a large, wealthy hunting population and a colourful history of African big game hunting featuring iconic characters such as President Theodore Roosevelt, whose year-long African safari is the stuff of legends. In 1909, he and his son bagged over 500 big game, including 17 lions, 11 elephants and 20 rhinos.

The USA is by far the largest market for trophies. The key drivers seem to be a large, wealthy hunting population and a colourful history of African big game hunting featuring iconic characters such as President Theodore Roosevelt, whose year-long African safari is the stuff of legends. In 1909, he and his son bagged over 500 big game, including 17 lions, 11 elephants and 20 rhinos.

Author Ernest Hemingway added to the allure with his 1933 safari, publishing evocative stories about men ushered into manhood by slaying African beasts. He was a romantic character with whom many American men still identify.

The American hunter has weaved his way into African hunting history despite never belonging there

The American hunter has even weaved into African hunting history despite never belonging there. In the film ‘The Ghost and the Darkness’, based on the true story of the man-killing Tsavo lions, “famous” American hunter Charles Remington (played by Michael Douglas) is commissioned to hunt the beasts. But he is an entirely fictional character, conveniently named after one of America’s largest arms manufacturers.

In ‘Out of Africa’, Robert Redford retains his American accent despite playing the Englishman, Denys Finch Hatton. In one crucial scene, he and Meryl Streep (playing Karen Blixen) come across a pair of lions. The female charges. Streep drops her with a single shot. But the male attacks from another direction, and Redford fires both barrels. The king obliterated, Redford takes charge, commanding: ‘Reload now.” They wait, rifles at the ready. Once the threat is over, they lower their rifles, and Redford notices the recoil from Streep’s rifle has split her lip. So he unwinds his sweaty neckerchief and dabs it on the bloody wound. It’s hot, heroic stuff.

Right: Ernest Hemingway posing with a lion during his 1933 safari.

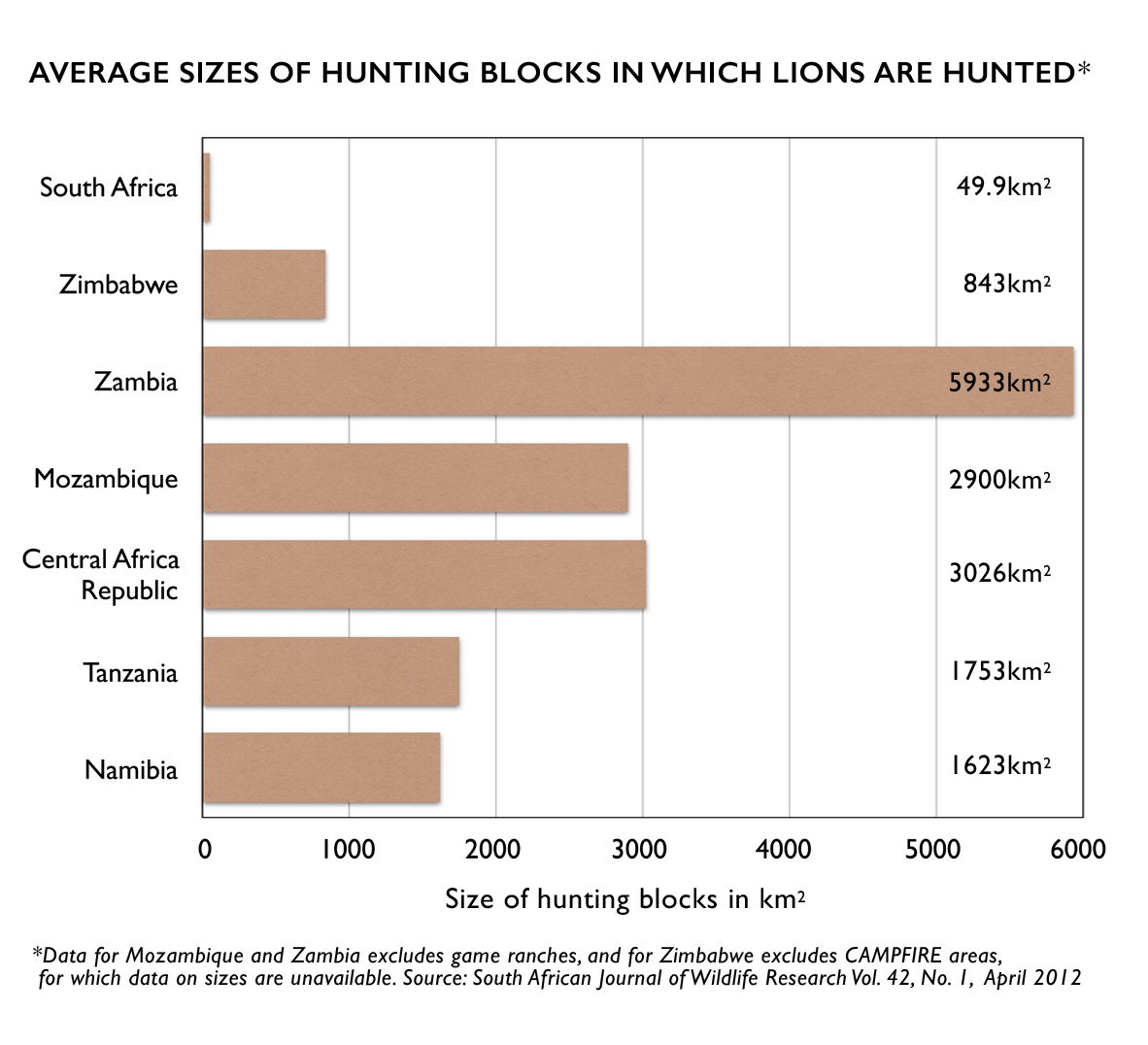

Today, killing wild lions is an expensive exercise involving many hunting days with no guarantee of success. In data collected between 2009 and 2012, the average cost of a lion hunt in Tanzania was US$76,116 lasting over 12 days, with an average success rate of 61.3%. In South Africa, you could bag a lion in 3 days with a 99.2% success rate at half the price or less. A minimum quote in 2012 was US$19,472.(1)

So why the huge price difference? For one thing, Tanzania abides by the hunting principle of ‘fair chase’. The lion has a relatively fair chance because of the size of its range. Here, lions are hunted in hunting blocks that average 1753 km². In Zambia, they average almost 6,000km². That makes for a long, difficult hunt. By all accounts, the lions hunted in these countries have lived in the wild and can use their well-honed instincts to escape from hunters.

In contrast, the hunting blocks in South Africa average 49.9km². Secondly, most lions hunted in South Africa are captive-bred, often hand-raised and accustomed to humans. Thirdly, they are only exposed to the “wild” for a short period before they are hunted in what is known in hunting circles as ‘put and take.’

The South African Predator Association stipulates a minimum of 10km² hunting area for captive-bred lions. The legally required release period for captive-bred lions in the Free State Province and North West Province is 30 and 4 days, respectively (FS and NW are where most captive-bred lions are hunted)(2). It sounds like canned hunting, doesn’t it?

The South African Predator Association stipulates a minimum of 10km² hunting area for captive-bred lions. The legally required release period for captive-bred lions in the Free State Province and North West Province is 30 and 4 days, respectively (FS and NW are where most captive-bred lions are hunted)(2). It sounds like canned hunting, doesn’t it?

In response to previous outcries against canned hunting, a 2007 ruling instituted by the Ministry of Environmental Affairs and Tourism stipulated that animals be allowed to roam free for 24 months before they are fair game for hunters. But this was overturned by the high court after an appeal by lion breeders. And so the business thrives. By 2010 the number of captive-bred lion trophies exported from South Africa was double the number of wild lion trophies from all other countries in Africa put together.

Price and a 99.2% guarantee are not the only attractive things for hunters. Captive-bred lions yield larger, better-looking trophies. Consistent food supply during growth helps achieve this, as does selective breeding, which is a widespread phenomenon on South African game ranches, so there is little doubt lion breeders practise it. Of Safari Club International’s record book of trophies in 2009, South African skull sizes top the list.(1)

Selective breeding has also led to more ‘exotic’ variants, such as white lions, for which hunters will pay a premium. It’s not just Siegfried and Roy who are in the market for a platinum blonde.

They are indeed attractive, enigmatic creatures, and perhaps one of the greatest evolutions of the industry has been for lion breeders to allow tourists behind the fence. Some of the largest breeding operations also run tourism programs (with no obvious connection to hunting) whereby lion cubs can be petted, and visitors can walk with juvenile lions. The lion petting and walking industry has flourished, with most tourists under the impression they are contributing to conservation by doing so – the operators’ spin is that the lions are bred for release into the wild or for research programs that benefit wild lions. Alongside tourists are young, impressionable “voluntourists” who assist the operators by looking after the lions and tourists, often paying for the privilege.

But few of them consider where all those lions go once they get too old to walk with tourists. Inevitably many of them are laundered into the hunting industry via a slick and secretive network of agents and front companies. These additional revenue streams must be appealing if you consider the overheads of these large operations.

But for captive-bred hunts, SAPA stipulates:

– Minimum interaction with the human environment from birth.

– No hand rearing.

– General “hands-off” management techniques concerning feeding, husbandry, medical care and environmental enrichment.

– No trade in human-imprinted animals.(2)

The reason for this is twofold: A lion familiar with humans will be a much easier target for a hunter, and a lion with less fear of humans will be more likely to attack if wounded.

The ethical issues involved in put-and-take hunting have been widely scrutinised and led to some hunting organisations distancing themselves from the practice. Safari Club International differentiates between lions hunted behind fences and ‘free-range’ lions. In effect, if you’ve shot a lion anywhere in South Africa, no matter how big it is, it will be categorised as an ‘Estate’ lion. As prominent American hunter Craig Boddington put it: “I’m shown a picture of a magnificent lion, so resplendent in the mane that it is extremely unlikely it’s a wild lion. Of course, it’s a South African lion, so now there is little doubt about the actual circumstances.”(3)

Backing up the trade in lions for hunting is the dubious trade in lion bone. Chinese manufacturers of tiger bone wine, believed by many Asians to have strong medicinal properties, reached a hurdle when trade in tiger bones was banned in 1993. But the sale of lion bones is not prohibited in China. Now the words “Panthera Leo” are printed on the wine label, indicating that lion bones are used. Research shows that the number of lion bones exported from South Africa has grown recently, indicating breeders must be capitalising on the market(2). And so the commoditisation of the king of beasts evolves and changes form to meet demand and supply.

Commoditisation of the king of beasts evolves and changes form to meet demand and supply

One argument is that the revenue from captive-bred lion hunting benefits conservation, but indications are that the trickle-down to genuine conservation efforts is marginal compared to the revenue that regular tourists bring in, often just to observe lions in the wild. It makes sense that a wild lion, with thousands of photographic tourists paying to see it over its comparatively long lifetime, will bring in more revenue than a lion bred to be hunted by one person.

Another argument is that captive-bred hunting alleviates the pressure on wild lions. But wild lions are under far greater threat from increasing habitat loss due to human population growth and land utilisation. Captive-bred lion hunting will not put a stop to that. In addition, there appears to be an offtake of wild lions from some African countries to supply new genetic material for South African captive breeding operations.

Ultimately we are not at risk of losing the species as long as there is a market for them. Like cattle, they will be bred, and they will thrive. But this is about saving a king, not a cow.

We need to protect all wild African lions and the wilderness that they depend on, or the creature that we put on the throne so long ago will have no dominion. He will cease to be king. He’ll be a rug for us to walk over and only live in our myths and legends, a reminder of what we once believed ourselves to be.

References:

(1) South African Journal of Wildlife Research Vol. 42, No. 1, April 2012

(2) South African Predator Association

(3) Sports Afield

(4) Campaign Against Canned Hunting

ALSO READ: Is lion hunting sustainable?

Contributors

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, sometimes drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton strongly empathises with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote, environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, sometimes drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton strongly empathises with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote, environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()