Something stirs in the depths, and for a moment, a shard of light illuminates the unmistakable scarlet rays of a pectoral fin. A nervous Maloti minnow emerges from the shelter of his watery lair – a flash of vibrance in an otherwise muted world. A plume of grey cloud seeps out from the peaks above, casting a shadow across the water, and almost as suddenly as the fish appeared, it is gone.

This is one of the last Maloti minnows still living in the Senqunyane River that snakes its way through the dramatic Lesotho Highlands. Unlikely to ever find a mate, and even if it could, the chances of its young surviving would be slim to none. A population doomed and a species teetering dangerously on the edge of extinction.

Things weren’t always this way in the Senqunyane. This mighty river pulsed with indigenous fish life not so long ago, and Lesotho’s iconic Maloti minnows swam these waters in their thousands. Groups of adults boldly patrolled submerged boulders for a tasty morsel of aquatic invertebrates. Swarms of young fish buzzed in quiet backwaters fringing deep pools, destined to live long and one day spawn themselves.

“What a whopper!” was the exclamation as three men marvelled at the beauty of a Maloti minnow held up in a plastic bag in the popular 1980s Mazda commercial! It was unthinkable that a species in clear view of the public eye and so widespread just a few decades ago could now be facing serious risk of extinction in the wild, but this is a story all too familiar in a world where we are ‘developing’ our land (and river) scapes faster than we can take stock of the environmental consequences.

The Maloti minnow (Pseudobarbus quathlambae)– Lesotho’s only endemic freshwater fish – is a member of a group of small but charismatic species collectively called the ‘redfin minnows’. These fish are notoriously threatened by habitat loss and species invasions throughout their ranges in South Africa, and a recent study published in the international scientific journal Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems reveals that Lesotho’s Maloti minnow may, in fact, be the worst off of the lot.

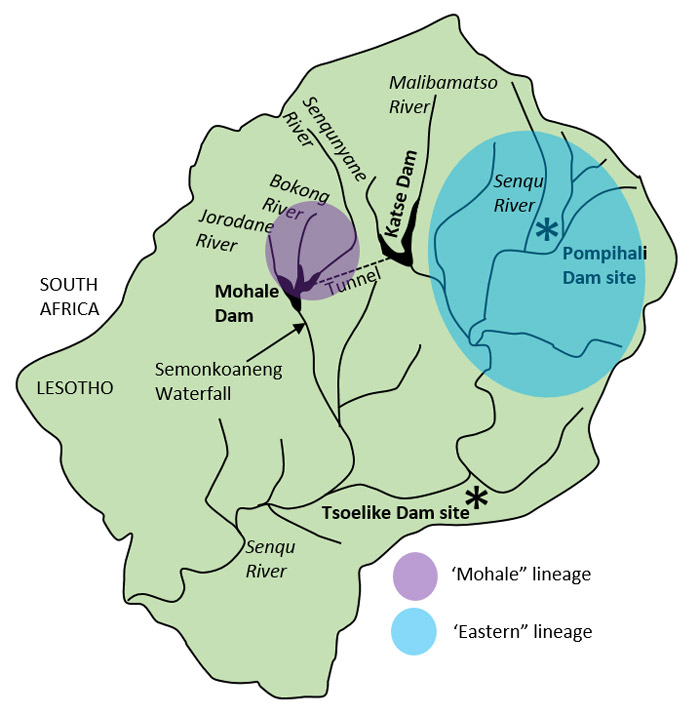

The species comprises two separate lineages that are genetically very different: a ‘Mohale’ lineage found in the rivers flowing into Mohale Dam and an ‘Eastern’ lineage that includes populations in river catchments east of Mohale. The large genetic difference between the two lineages results from a long period of geographic isolation. According to freshwater fish expert Professor Paul Skelton from the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB), this means they should be conserved separately.

Furthermore, the Mohale lineage occupied three-quarters of the total habitat occupied by all Maloti minnows before the construction of the Mohale Dam and was thus identified as being of critical importance for the continued survival of the species. For aeons, the Maloti minnow was the only fish species inhabiting the upper Jorodane, Bokong and Senqunyane Rivers (which now flow into Mohale Dam) and is consequently poorly adapted and highly susceptible to predation by larger species of fish. Although present downstream, larger species like yellowfish and trout have historically been prevented from moving into these rivers and coming into contact with the minnows by the spectacular 20-metre-high Semongkoaneng waterfall.

However, following the filling of the Mohale Dam in 2003 (the second of four major dams planned for the Lesotho Highlands Water Project, with Katse Dam being the first), an underground tunnel linking it to the neighbouring Katse Dam was opened. Aquatic biologists immediately saw the potential for larger species like yellowfish and trout present in Katse Dam to travel through the tunnel to Mohale Dam and spread up into the influent rivers with potentially disastrous consequences for the Maloti minnows.

They sounded the alarm and lobbied for measures to be put in place to prevent this scenario from unfolding. Unfortunately, their advice was not heeded, and now, nearly a decade and a half later, the inevitable has happened – smallmouth yellowfish (Labeobarbus aeneus), a larger, more aggressive species, has moved through the tunnel, spread up into the Jorodane, Bokong and Senqunyane Rivers and all but displaced the naïve and fragile Maloti minnows from these former strongholds. Orange River mudfish (Labeo capensis), another large cyprinid, have also recently shown up in the dam, and who knows how long it will be before trout (rainbow trout – Oncorhynchus mykiss, and brown trout – Salmo trutta, both present in Katse Dam) do the same!

Large-scale developments like the Lesotho Highlands Water Project are vital for providing clean water to thirsty developing nations like South Africa and Lesotho, but at what cost? How many more unique species need to be lost before we start prioritising their well-being in our plans to develop our last wild places? Indeed, a world without its unique creatures is like a ring devoid of its sparkling diamonds. In the case of the Maloti minnow, this ecological disaster could easily have been prevented with a simple engineering modification to the Katse-Mohale water transfer tunnel. We now have an opportunity to learn from our mistakes and avoid similar oversights in the construction of Pompihali and Tsoelike Dams (stages three and four in the project) and, indeed, the development of our planet’s ecosystems in general.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()