“The leopard moves as silently as mist drifting on a dawn wind.” – Indian proverb

The spiked mountain range of uKahlamba in South Africa is often called the barrier of spears. Also known as the Drakensberg, which translates to ‘dragon mountains’, its high, jagged peaks shadow a cave hidden in a sandstone cliff. The cave once concealed creatures that stirred only with the setting sun – leopards.

To reach the animal’s hide-out, a hiker must scale Solar Cliffs and Cathedral Peak and pass through Ndedema Gorge. Not everyone survives the journey.

A modern sign near the cave’s entrance announces it is ‘Closed’ as if its dweller had served notice. The inhabitant was a leopard, its lair called Leopard Cave.

Near this opening in the Earth is a rock painting of a leopard chasing a bushman who escaped to return another day to tell his tale in art.

The leopard likely had good reason to give chase and eventually vacate the premises. Its species, Panthera pardus, has been overhunted and harassed and lost much of its habitat and its prey.

A blind spot in conservation

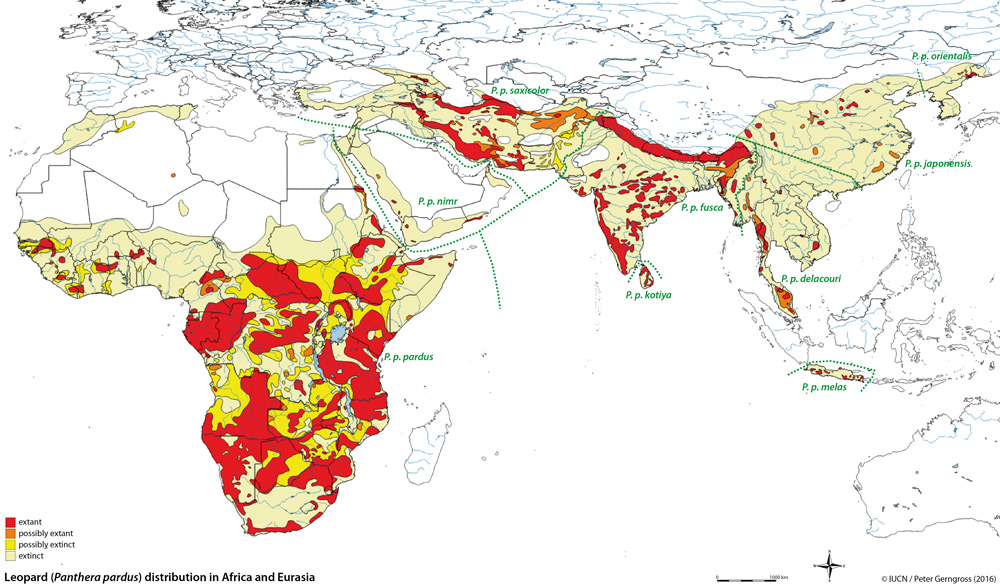

Smallest in the genus Panthera – of which lions, tigers, and jaguars are also members – leopards (Panthera pardus) once lived from Siberia to South Africa.

But the cats have relinquished as much as 75 per cent of their range, according to a paper published in May 2016 in the scientific journal PeerJ. The study — sponsored by the National Geographic Society’s Big Cats Initiative and conducted by its scientists and others affiliated with the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), Duke University, Panthera (an international cat research and conservation organisation), and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Cat Specialist Group — is the first to produce a comprehensive analysis of leopards’ status across their entire range and for all nine subspecies.

The PeerJ co-authors found that leopards long ago occupied a vast range of approximately 35 million square kilometres throughout Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Today, however, leopards are restricted to about 8.5 million square kilometres. In Africa, range loss varies by region – as much as 99 per cent in North Africa, 86 to 95 per cent in West Africa, and 28 to 51 per cent in Southern Africa.

The scientists created the most detailed reconstruction to date of the leopard’s range, says paper co-author Peter Gerngross, a cartographer at the Austria-based mapping firm BIOGEOMAPS.

The biologists reviewed more than 1,300 sources to derive the leopard’s historic (post-1750) and current range.

“Contrary to the pervasive impression of the leopard as one of the most widespread, adaptable and resilient carnivores,” the researchers reveal in their paper, “our calculated range loss exceeds the average range loss for [17 species of] the world’s largest carnivores.”

The results confirmed conservationists’ suspicions that leopards are losing the battle against a many-headed threat – habitat loss and fragmentation, human population density, conflict with livestock-keepers and game-keepers, loss of prey, killing for the illegal trade in skins and parts, and, in some areas, unsustainable but legal trophy hunting.

“Our results challenge the conventional assumption that leopards remain relatively abundant and not seriously threatened,” says paper author Andrew Jacobson of ZSL. “The leopard is an elusive animal, which is why it has taken so long to recognise its global decline.”

“The cat’s status is more grave than previously understood.”

Because of that downturn, the cats are currently listed as “Vulnerable” by the IUCN. According to Andrew Stein, a member of the group and co-author of the PeerJ paper, the organisation’s Cat Specialist Group recently recommended a change from Near Threatened to Vulnerable. “The change signals to leopard range countries that the cat’s status is more grave than previously understood,” he says. “It begins a process of deeper evaluation, including calls for greater protection and intensified regulation of trade and trophy hunting.”

Philipp Henschel of Panthera, also a paper co-author, adds that “a severe blind spot has existed in the conservation of the leopard, especially in North and West Africa. The international conservation community must support initiatives protecting the species. Our next steps will determine the leopard’s fate.”

Leopard findings

Leopards are part of what’s called the large carnivore guild, which includes lions and hyenas. An ecological guild is a group of species that exploits the same resources. “The large carnivore guild is mostly intact in protected areas,” says South African National Parks biologist Sam Ferreira. “These are the places where leopards still thrive and have relatively large populations.”

Results of a camera trap survey Ferreira conducted in the N’wanetsi concession in Kruger National Park in 2008 led to an estimate of 19 leopards in a 150 square kilometre area. He and colleagues published the results in 2013 in the African Journal of Ecology. The biologists continue using camera traps to study the park’s leopards.

Next door at the Sabi Sand Game Reserve, biologist Guy Balme of Panthera is working with safari guides at more than 20 lodges to track leopards. “Because of the large number of vehicles in Sabi Sand and the reserve’s long history of protection,” says Balme, “leopards have become habituated to game drives.” Guides are familiar with the leopards in their areas. “Their unique spot patterns can distinguish individual leopards,” says Balme, “so we’ve been able to monitor their fates over time.”

Biologists and safari guides have tracked more than 600 leopards over the last 37 years through the Sabi Sand Leopard Project. The results align with Sabi Sand’s protected, stable leopard population.

Across the continent in West Africa, however, the news isn’t as good. From 2009 to 2012, Henschel led big cat surveys in 21 of the region’s largest protected areas. His team’s efforts were rewarded – to some degree. “We found leopards in seven of the 21 areas,” he says, “but only one of these populations numbered more than 100 individuals.” Fewer than 500 breeding-age leopards may remain in the entire West African region, Henschel believes.

He and Luke Hunter, president of Panthera, and scientists at the U.K.’s University of Oxford and other institutions, have identified another threat to Africa’s leopards – competition with bushmeat hunters for the same food source.

Their research, reported in the Journal of Zoology, took place in the rainforests of the Congo Basin. It shows that bushmeat hunting is likely responsible for a dramatic drop in leopard numbers in the Congo. Leopards have vanished without a trace in the most over-hunted of the project’s sites.

“A critical part of protecting big cats and their landscapes is documenting the presence and behaviour of wild cats using camera traps,” says Hunter. “Panthera’s motion-activated cameras collect hundreds of thousands of wildlife images every year. With help from the public, we can analyse these photos to identify the animals shown, enabling us to track wild cat population trends over time and determine what conservation actions are needed to protect these species better.”

Survival instincts

Wherever leopards manage to eke out a successful living, they do so by stealth. They’re camouflaged by their spots, blending into the dappled shade of trees and rock piles.

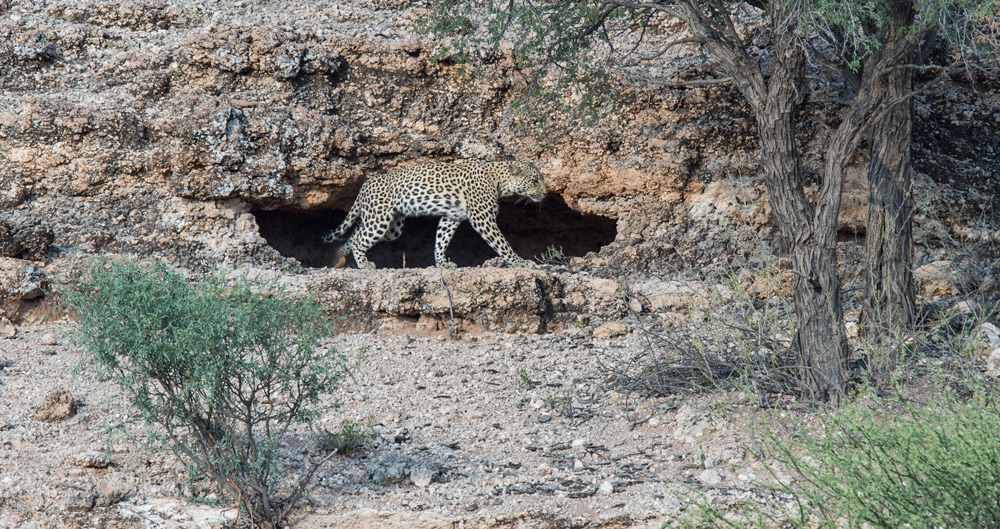

Leopards are also furtive in other ways. They mainly come out at night. By day, studies have shown, leopards hide in dark recesses such as caves. In hot, dry environments, leopards use caves to escape high temperatures. “Leopards are secretive predators, making use of caves as retreats, feeding places, and breeding lairs,” states palaeontologist Charles Brain in his book, The Hunters or the Hunted?: An Introduction to African Cave Taphonomy.

In South Africa, scientist Darryl de Ruiter of Texas A&M University discovered one such leopard cave in Malapa Nature Reserve. “In contrast to the ‘leopard in the tree’ idea that these cats cache their kills most often in large tree branches,” says de Ruiter, “they may well prefer to use the deep recesses of caves,” as vultures, hyenas and lions, which might steal a leopard’s kill, usually won’t enter, and caves may give leopards the ability to store larger prey. Most caves in the Highveld area of South Africa have trees growing in their entrances. “Nonetheless,” says de Ruiter, who published his findings in the Journal of Archaeological Science, “leopards haul carcasses into caves, avoiding trees entirely. In our study, 83 per cent of the cached carcasses were in caves, and only 17 per cent in trees.”

A look at the future

Our ancestors may have been intimately familiar with leopards, ancient cave paintings in Europe tell us. But a question asked by biologist Theodore Bailey in The African Leopard: Ecology and Behavior of a Solitary Felid remains: “Will wild leopards survive to evoke the admiration of our far-away descendants as they once did our distant ancestors?”

Recently reported sightings of erythristic, or ‘strawberry pink,’ leopards in South Africa’s Lydenburg region of Mpumalanga may be an indication. Scientists recently reported in the journal Bothalia: African Biodiversity & Conservation that “the presence of this rare colour morph may reflect the consequences of [leopard] population fragmentation.”

Leopards can survive in human-dominated landscapes if they have enough cover, access to wild prey, and acceptance by local people. But in many areas, leopard habitat has been converted to farmland, and native herbivores have been replaced with livestock.

Scientists believe it is mostly a matter of developing tolerance to leopards’ presence. Leopards are usually quiet neighbours and, in many locations, they’ve long-lived among us. However, successfully sharing the same territory will take some adjustment on the part of humans. Livestock owners, for example, may need to develop new ways of guarding their herds.

“It’s not asking too much of people to give thought to the welfare of these cats,” says Stein. “Leopards badly need the reprieve.”

Read more about leopards here.

About the author

Ecologist and science journalist Cheryl Lyn Dybas, a Fellow of the International League of Conservation Writers, fell in love with Africa and its savannas at first sight. She lives in the U.S., outside of Washington, D.C., and also writes on Africa and other subjects for National Geographic, BioScience, Natural History, National Wildlife, Scientific American, Oceanography, The Washington Post, and many other publications. She is a featured speaker on conservation biology and science journalism at universities, museums and other institutions. Eye-to-eye with the wild is her favourite place to be.

Ecologist and science journalist Cheryl Lyn Dybas, a Fellow of the International League of Conservation Writers, fell in love with Africa and its savannas at first sight. She lives in the U.S., outside of Washington, D.C., and also writes on Africa and other subjects for National Geographic, BioScience, Natural History, National Wildlife, Scientific American, Oceanography, The Washington Post, and many other publications. She is a featured speaker on conservation biology and science journalism at universities, museums and other institutions. Eye-to-eye with the wild is her favourite place to be.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()