Two Australians who are just crazy about Kruger

We’re a couple of Australians from Perth who are mad about South Africa and feel that there is nothing quite like the experience of visiting Kruger National Park in particular. We’ve been at least 25 times and almost always stay for six weeks at a time, which makes our friends and family ask: “Why are you returning to the same place yet again?” They assume it must be boring and repetitive, but they don’t realise that it is very different in unpredictable ways every time and every day.

Kruger National Park is a vast area of about 19,485km², which is 360km long and about 65km wide, making it the size of a small country. And visiting Kruger can be an enriching adventure if you tackle it right! Sure, you can go on an all-inclusive safari where you will stay in luxury lodges and be driven around, but you could also do it yourself and indulge in the same serendipity for a lot less money. This serendipity comes from seeing what offers itself up to be seen – where what you see next is determined by what you stop to look at along the way.

Kruger offers us a fantastic opportunity to drive ourselves, stay in a small, thatched rondavel, and cook simple food. The trappings of Western life don’t belong here – television, the 24-hour news cycle, instant access to everything, constant phone calls and emails, and so on. We feel a deep, almost primaeval, satisfaction in finding our ‘own’ birds and wildlife. It feels good to connect with our pure instincts and be reminded of adrenalin’s real purpose – not for stress in the workplace, but for basic survival in the wild.

You do not know what will expose itself from one moment to the next. Each day, what you see or don’t see is determined by the stops you make along the way, a bit of skill and some luck. Ultimately, this combination determines whether you have the most amazing time with a leopard or miss out on seeing it!

We may have stayed in some upmarket places over our years of visiting Africa, but the place we always miss and yearn for is Kruger, where our souls get mended and restored without having to do anything to make it happen.

Let’s take it back to the start

How did our obsession with Kruger begin? We first visited South Africa in 1994 as members of an Australian-South African scientific symposium on river classification and management. The meeting was to start in Kruger at the conference centre in Skukuza, so we decided to arrive a few days early. As soon as we had flown into the park and collected our rental minivan at Skukuza Airport, we headed off for a life-changing experience.

We drove out of the Skukuza Airport gate and agreed that the first one to find a big animal would buy the other dinner. Sally saw an impala after about 30 metres but protested that it wasn’t really that big! Then, almost immediately, she spotted a colossal giraffe browsing on thorns – now that is a big animal. She bought dinner.

We vividly remember stopping on the Sabie River causeway near the airport and being transfixed by the amazing birds we’d never seen before. One was black and white with a long tail and a lolly-pink beak, and the other was a pied kingfisher hovering before diving to catch a fish. We didn’t know where to look! As we arrived at Johannesburg airport very early that morning, we’d had a chance to load up on bird books and mammal guides at the airport bookshop, but we had no idea how to look up a bird we’d never seen before. With Bob driving, it fell to Sally to thumb through the book until she found the bird with the lolly-pink beak. It was a male pin-tailed whydah, and this method of thumbing through the bird guide became a great way to familiarize ourselves with a range of new birds quickly.

All about Kruger

Kruger has a subtropical climate and a wide range of habitats that change from west to east and south to north as the underlying geology, soils, and average rainfall varies. In general, the park is relatively flat. Still, the topographic monotony is broken by the Lebombo Mountains bordering Mozambique to the east, the Muntshe and Nkumbe hills, the hilly southwest area around Pretoriuskop and Berg-en-Dal, and the spectacular escarpment overlooking the Olifants River, which is one of our favourite views in the world.

Kruger is relatively well-vegetated and lacks the sweeping plains of East Africa. The southern half of the park supports thorny acacia and bush-willow savannah, and this zone has a greater variety of plants than the seemingly endless mopane scrubland that lies further to the north. Open grassland with large herds of wildlife is rare but can be seen around the park’s centre. The ‘bushy’ nature of Kruger means that it is often harder to find animals – some estimate that only 2% of the park is visible from its extensive network of tar and dirt roads. However, despite this, the fantastic array of birds is always visible, and you usually spot animals every 15 to 20 minutes unless the weather is poor.

The varied habitats support an extraordinary range of plants and animals – about 500 species of birds, more than 145 mammals, lots of frogs and reptiles, and innumerable insects. On our last trip, we spotted 45 mammal species and over 300 birds, and there are very few places in the world where this is possible!

Where to stay

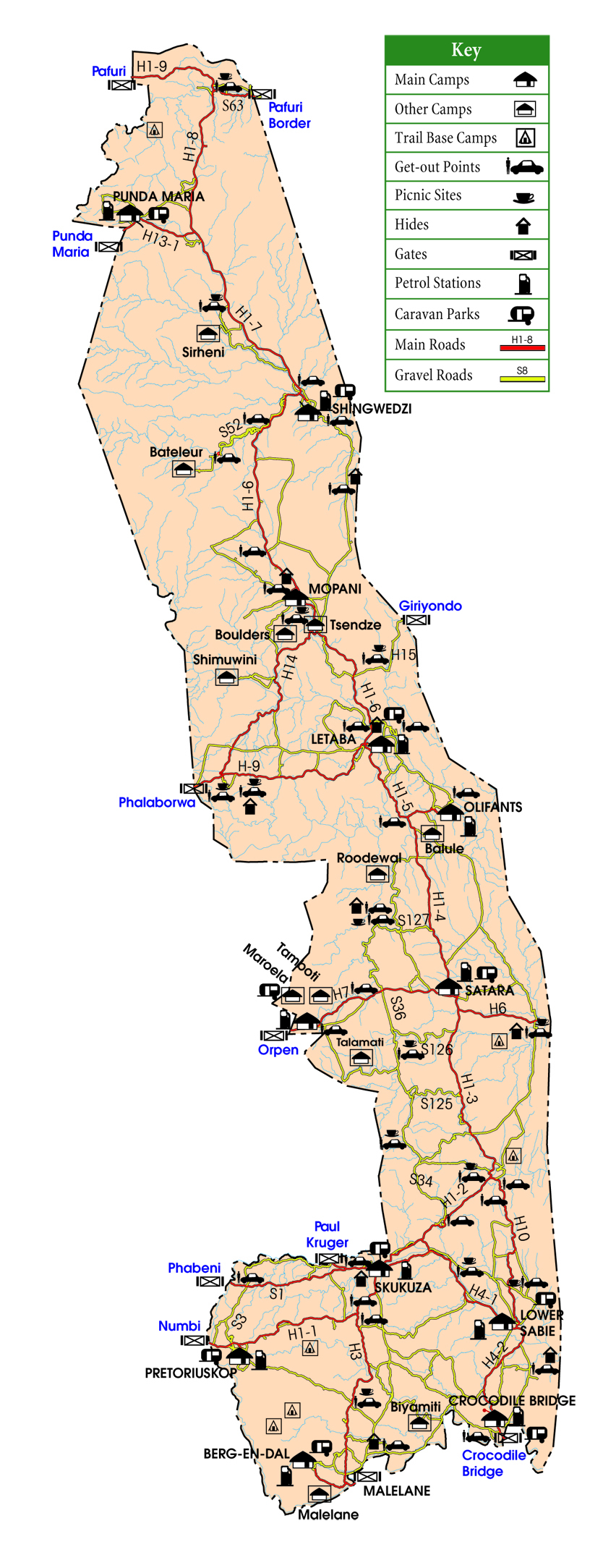

The 13 main rest camps are well located throughout the park to provide easy access to this spectacular diversity and enable drivers to travel from east to west across the ecozones or from north to south. The fact that the park has been mapped into ecozones makes it unique, and the ecozone guidebook is cheap. The main camps provide accommodation options of bungalows, permanent tents and DIY camping grounds. The available cottages, usually thatched, are comfortable, well-priced and adequately equipped (except none have a sharp knife). There are also five rustic bush camps and luxury game lodges on private concessions, so there is plenty of choice.

Find out about the Greater Kruger for your next African safari – find a ready-made safari or ask us to build one just for you.

Find out about the Greater Kruger for your next African safari – find a ready-made safari or ask us to build one just for you.

We mostly stay in the park for five to six weeks, beginning in the south at Crocodile Bridge or Berg-en-Dal and gradually working our way north to Shingwedzi Rest Camp or Punda Maria Rest Camp, staying three to five nights in each camp, before turning south again. This maximises the opportunity to discover the local specials, and avoids the problem of packing, moving and unpacking all of the time. Instead, we unpack once at the beginning and rely on using themed carriers, such as what we call a ‘bathroom bag’ and a ‘kitchen bag’. We then only pack up when we have to leave.

When to visit

Our favourite time to visit is in late October to early November onwards, as we hope to catch the beginning of the rains when the biology of the park just explodes. Within a few days of the start of the season, impala ewes have lambed, green grass appears, leopard tortoises drink from puddles on the road, migratory birds arrive, and the stunning weaver finches begin breeding. This is not the easiest time to see mammals, as it’s sweltering and there is water everywhere, which means that the game is less dependent on formal watering points. Still, the considerable level of activity and the diversity of sightings outweighs this. Whereas in February and March the grass is tall, so we find spotting game to be challenging.

Many people consider the dry winter months best for game viewing due to the bush being less dense and the tendency for wildlife to congregate at waterholes.

However, due to the local school holidays in June and July, and the fact that this is low-risk malaria season, this is also the busiest time at Kruger.

A bit of advice from the pros

We discovered early on that the best way to have a profoundly satisfying visit to Kruger is to be interested in everything. This is because finding things isn’t as easy as it seems in wildlife television programmes about Africa. Some days there is so much happening that we hardly know where to look, whereas, on slow days with little mammal or bird activity, we choose to focus on the plants and insects instead.

We have lost count of the number of times that we’ve stopped to observe a bird to be asked by someone what we are looking at before they drive off as soon as they realise it’s ‘only a bird’. But then a lion pops its head up from under the bush that the bird was in! Patient observation is the way to go, and taking the time to watch the natural behaviours, even of common animals, is rewarding and often surprising.

Kruger National Park has fantastic maps and guidebooks for sale, and South African National Parks has an excellent website. We mostly self-cater by shopping in one of the towns bordering the park at the beginning of our stay, and sometimes again half-way through our holiday. The park shops have a limited range of food and sometimes run out of things during busy times, so it’s essential to plan. We also pre-order good wine as the park shops don’t tend to stock South Africa’s best drops. The park restaurants are fine, but it’s part of our ritual to light the braai and wait for the coals to form as we sip gin and tonics, listening to the night sounds and reliving the day.

Please don’t speed – show respect and give animals the space to move

Safety around the wildlife is critical, so please don’t speed – show respect and give animals the space to move. Don’t reverse if a bull elephant blocks the road; this signals fear and submission, which keeps the elephant engaged. Instead, turn around and drive two to three kilometres away before turning off the engine and waiting 10 to 15 minutes for the bull to become bored and go back into the bush.

What to bring

– A pair of good binoculars are essential to see things up close – we suggest 8x32s as they are not too heavy.

– Hire a large, tall vehicle – we like the VW Kombi T5 the best.

– Be prepared for a range of hot, cool and wet weather.

– Carry insect repellent and a cortisone cream to treat bites.

– Take wildlife and plant guides, or download some of them as smartphone apps.

– Bring a camera with at least a 300mm lens to avoid getting disappointingly distant shots.

– Stock up on food and supplies outside of the park, and take a couple of cooler boxes as you may want access to food and drinks when you are not allowed out of your vehicle.

About the authors

Sally Robinson cut her teeth on zoos and Gerald Durrell’s books and loves seeing animals in their natural environment. She was Deputy Chairman of the Western Australian Environmental Protection Authority and works as an independent environmental consultant. She has won awards for her work in environmental protection and policy development. She is now a wildlife photographer.

Dr Robert (Bob) Humphries is a systems ecologist with a PhD in frog ecology. He has worked as an environmental consultant for the Western Australian EPA and the Australian water industry. At heart, he’s a naturalist, so his recent retirement is great – it means more time in the bush with his video camera.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()