A brave new drive to protect an iconic paradise

EDITORIAL NOTE: Subsequent to the publishing of this feature, the Niassa Wilderness contract to manage this concession was terminated by the son of Adel Aujan and trophy hunting resumed

“Are we seriously landing there?” The Cessna Caravan was heading towards a massive rocky dome, and what appeared to be a short dirt track in a dense sea of woodland. But, as we skimmed over a wide sandy riverbed, the track morphed into a landing strip. We bumped down and taxied to a halt. Paradise found. Niassa.

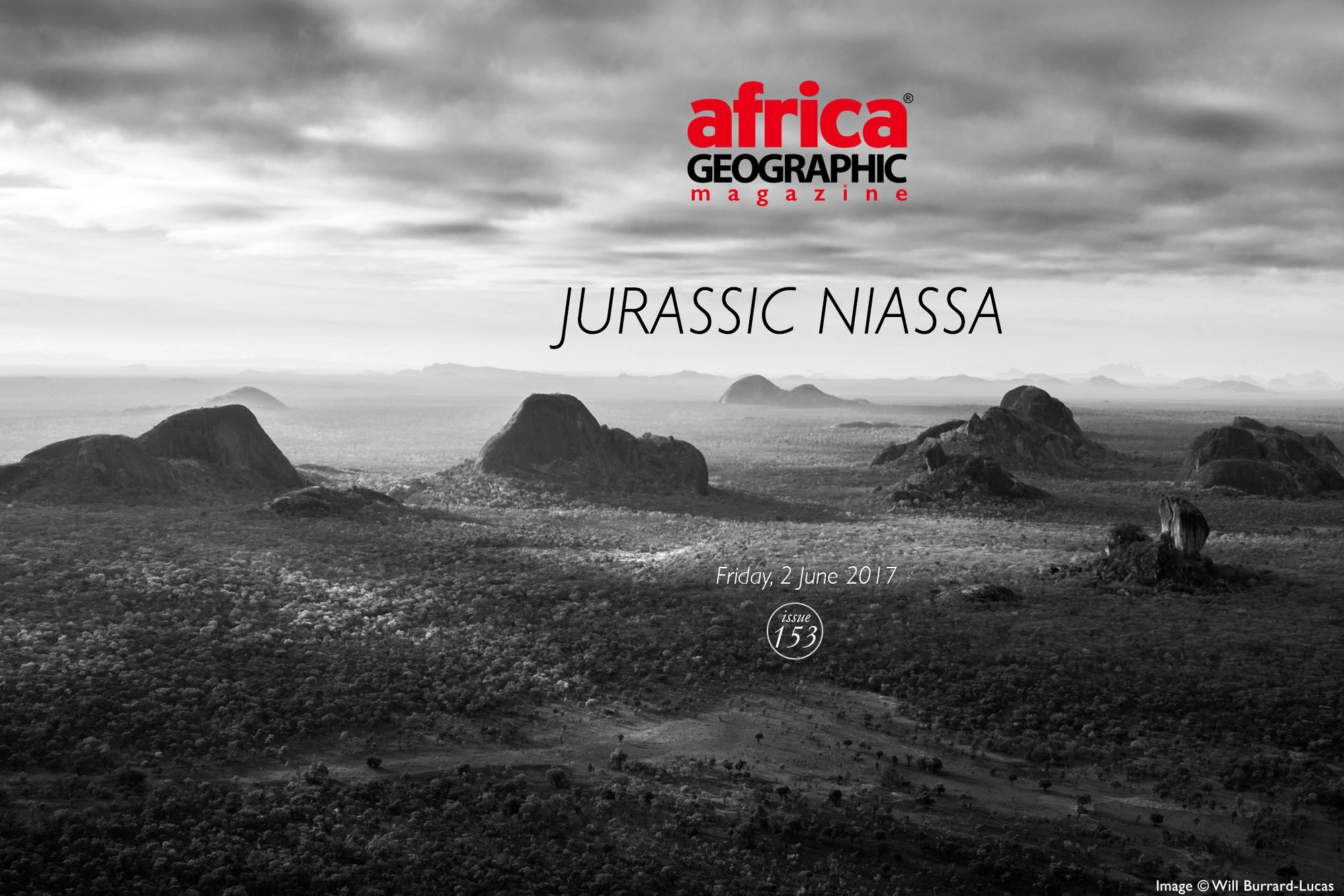

This landscape leaves me speechless. ‘Jurassic’ is possibly the best way to describe it. Yet, there is so much more to it than that. There is a powerful presence here, a heady blend of raw fecundity and ancient whispers that sets this vast landscape apart. This is how Africa used to be before it was colonised and reshaped.

This was my second visit to paradise. I was here to assist a special group of conservationists who are preserving the largest concession within Niassa National Reserve for the Mozambican people.

Stepping out of the Cessna and into the baking November heat, we were met by Director of Conservation and Law Enforcement Derek Littleton and his able team. Later that evening, Derek explained to our film and photographic crew that Niassa Wilderness is a privately managed concession within the Niassa National Reserve, comprising over 10 percent of the entire reserve.

The logistical realities of patrolling such a vast area are immense, especially during the rainy season when large parts of the reserve are flooded, making them inaccessible to all but determined poachers. During our brief visit, we came to appreciate how difficult the task is. This is illustrated by the plight of the elephants in the massive and remote 42,000 km² Niassa National Reserve. Rampant commercial poaching has caused elephant populations across the reserve to plummet by more than 70 per cent. In 2012 there were 12,000 elephants here; in 2016 only 3,500 remained.

At 4,450 km², the newly named Niassa Wilderness is the largest of 17 concessions in the national reserve. It hosts 20 percent of the entire elephant population and the largest number of intact breeding herds and mature bulls.

The Big Change

In 2000, Niassa Wilderness (then called Lugenda Wildlife Reserve, or ‘Luwire’) became the first concession in the reserve to be allocated and subsequently funded by a private investor. Since then, it has operated as a responsible trophy hunting concession.

A luxury photographic tourism lodge, Lugenda Wilderness Camp, was built in 2006 but closed at the end of 2015 to focus on anti-poaching efforts. It now serves as Niassa Wilderness HQ and as a venue for hosting donors and media teams. Due to the increase in elephant poaching, all elephant trophy hunting was voluntarily brought to a halt from 2012.

The new Board of Directors has decided to phase out all hunting and source funds from donors to fund anti-poaching efforts instead. The new funding model ensures authentic community inclusion and that 100 percent of donor funding will go into conservation and community activities. The Board of Directors serves voluntarily, and advice and assistance are drawn from a network of similarly philanthropic professionals.

One warm evening around the campfire, Derek explained the added level of complexity that makes this task so difficult. About 35,000 people are living in 40 villages inside the national reserve. Niassa Wilderness incorporates seven of those villages.

These isolated people have no access to jobs and have historically eked out a subsistence lifestyle from the bush. They fish, gather honey and hunt for bushmeat, skins and ivory. They also grow tobacco and food crops, which are raided daily by wild animals. Villagers are frequently attacked and sometimes killed, by crocodiles, hippos, elephants and lions.

In short, wildlife for these people represents either food or danger. Therein lies the conservation challenge. And, now that poaching has moved beyond subsistence levels into commercial operations, the challenge is exponentially more significant.

As we listened to a lion groan from somewhere in the pitch darkness, Derek remarked that he has a team of only 40 anti-poaching staff. That’s one person for every 11,250 hectares. To even begin to assert themselves on poachers, he’ll need a minimum crew of 75 people – one for every 6,000 hectares. This stark statistic puts the situation and his ambitions into sharp relief.

Trophy hunting in the concession has been strictly controlled and sustainably managed. It used to serve the vital role of preventing all but subsistence poaching. But, even a well-run hunting operation has been powerless to stop the rampant commercial poaching that has hammered elephant populations in recent years. Derek and his team now plan to increase the level of protection activities significantly. They also want to involve communities in the drive to purge the reserve of poachers.

The need for more military-style protection was driven home to me during a lengthy drive along rutted dirt roads to visit one of the seven villages within the concession. Brian Johnson, who manages the current trophy hunting activities, was at the wheel. I asked him why hunting is better than photographic tourism in keeping poachers at bay.

“Look,” he said bluntly, “a bunch of macho hunters packing 375s is a bigger threat to poachers than a carload of tourists packing Nikons.”

There you have it.

One evening, I was enjoying a spectacular African sunset on the banks of the Lugenda River with the new Niassa Wilderness CEO Greg Reis, a trusted and valued friend of long-standing. He shared his hopes for the future with me.

“We’re phasing out hunting in favour of donor funding,” said Greg. And we’ve made the communities and wildlife the beneficiaries of the trust. Our entire team, from the Board of Directors to management and dedicated hard-working anti-poaching rangers, has decided to be on the right side of history, to put Niassa before short-term monetary gain.”

He paused. “Now, surely, is the time for the anti-hunting fraternity to get behind this brave project. This is one of Africa’s last true wilderness areas, with excellent intact habitat. However, wildlife suffers under the massive pressure of poaching.

“We need funds to bring more local people from our communities onto the right side, to give them reason to protect wild animals and their environment. It’s time to move beyond words; it’s time to make a real difference.”

Perhaps one day Niassa too will offer adventurous travellers the opportunity to experience true African wilderness. Until then, the brave and visionary Niassa Wilderness team will hold the fort. Will you help them? A luta continua!

VISION AND COURAGE

Niassa Wilderness would not be possible without the vision and significant investment of Adel Aujan, a businessman who fell in love with Niassa. He was the first to sign up for an initial 25-year lease on the concession, and to invest in the reserve. Aujan passed away in January 2017, but his family continues their involvement in Niassa Wilderness.

IT’S ALL ABOUT CO-OPERATION

The Mozambican government manages its protected areas via the National Conservation Areas Authority (ANAC), which provides the legal framework for conservation activities in Niassa.

Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), working closely with ANAC, has overall management responsibility for Niassa Reserve and, amongst other things, provides vital coordination between the various concession holders in the reserve.

Vast wild areas like Niassa are best managed in close collaboration with neighbours who will support you while you do the same for them. Niassa Wilderness continues to work closely in partnership with neighbouring Niassa Reserve properties Mariri and Chuilexi, a formal alliance established from 2016, that serves all parties well.

NIASSA INFO

Size

Niassa National Reserve: 42,000 km² / 4,2 million hectares. (Twice the size of South Africa’s Kruger National Park.)

Niassa Wilderness (concession within the reserve): 4,450 km² / 445,000 hectares.

Location

Northern Mozambique, bordering Tanzania.

Habitat

Miombo woodland, granite inselbergs, open savannah, wetlands, river floodplains and riverine forest.

Wildlife

350 African wild dogs (significant in relation to the global population of an estimated 6,600 adults).

Endemic species: Niassa wildebeest, Boehm’s zebra, and Johnston’s impala.

Elephant, Cape buffalo, lion, leopard, hippo, crocodile, sable antelope, Lichtenstein hartebeest, Livingstone’s eland, common reedbuck, klipspringer and others.

Over 400 bird species.

Check out this gallery of superb Niassa images

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. He travels extensively in Africa, seeking wilderness, real people and elusive birds.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()