Guest blogger: Louise Swemmer

Of course it’s about the worm, but it’s not JUST about the worm. Harvesting mopane caterpillars from the Kruger National Park provides people with much-needed food and income, but it also does a lot of good for conservation.

Mopane worms (Mashondza in Xitsonga), the larva of the Imbrasia belina moth, are a widely used source of protein and a delicious snack, especially for people in the Limpopo Province of South Africa.

Unfortunately, since they are so popular, they have been over-harvested in many areas and can be quite expensive to buy. The Kruger National Park (KNP) started a Mopane worm harvesting project in 2010, to help local people to access worms both for food and for the harvesters to make a small income. Accessing benefits from conservation helps to build positive relationships between people and conservation areas (ask any tourist about their feelings towards conservation after they have just visited a game reserve!). Having positive relationships with society, especially with local communities, is not only the right thing to do but can be really important for the sustainability of protected areas such as the KNP. Especially now, when biodiversity needs all the support it can get.

Mopane worms occur all over Southern Africa, including in Mozambique, Malawi, Southern Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Northern South Africa, closely linked (but not exclusively limited to) wherever one finds mopane trees (Colophospermum mopane). Fully grown Mopane caterpillars have multiple coloured stripes, are about 10cm long and are covered in prickles which can make them tricky to harvest if you have soft hands. The best time to pick worms is just before they bury themselves underground to pupate into Mopane moths, that way they have high protein content and when it’s easier to expel the internal organs – a requirement before they can be eaten. The moths that emerge from the pupae are enormous, with two big false eyes on their wings, acting as a defence mechanism against predators. The moths lay a batch of tiny white eggs very soon after they emerge, which hatch about 21 days later. The tiny worms then start their journey to adulthood. The caterpillars shed their skin four times before they are ready to pupate into moths, and it is after the final shed that they are the tastiest!

The Kruger Mopane worms are harvested from a demarcated area less than 0.2% of the area of the KNP, within the vast Mopane veld found in the north of the park. The harvesting takes place once a year, in years when there is a large enough outbreak to provide worms for harvest as well as allow enough worms to descend into the soil to reproduce for following years. The outbreaks last between 1 and 2 weeks. Harvesters from local villages are invited to participate and issued with a permit. They are kept safe by the SANParks rangers while harvesting. People usually harvest about 25 litres of caterpillars per person, which can contribute the equivalent of half of a month’s income for some households.

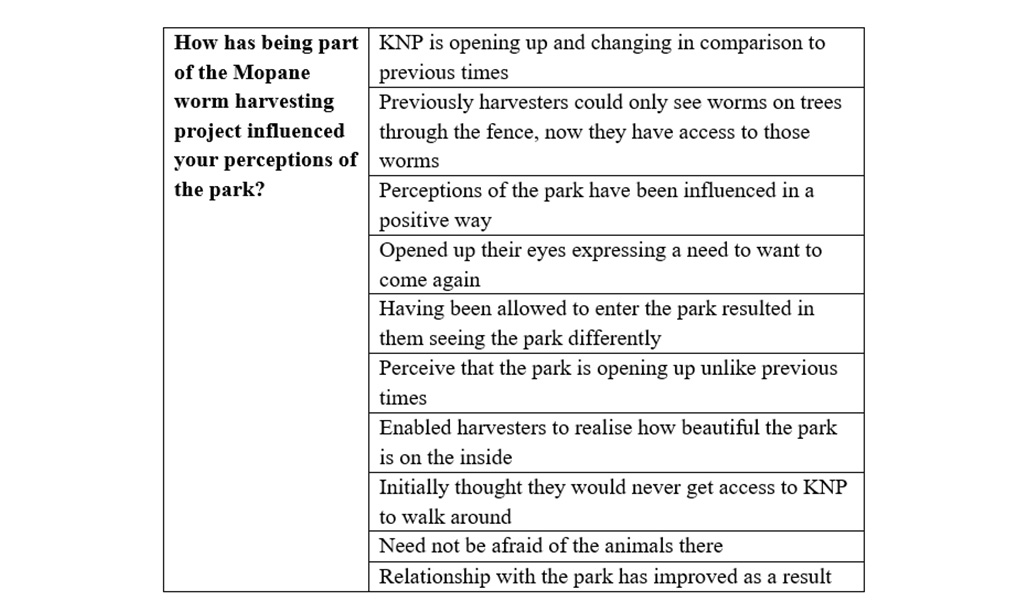

In a recent study, it was shown that apart from the nutritional and economic value of the worms, people who were part of the harvesting enjoyed the experience, feeling that the park is opening up to them, and seeing the park more positively as a result (Table 1). For most participants, the project provided them with their first chance to visit the park, and many enjoyed the opportunity to learn and experience new things (Figure 1). Apart from enjoying nature, a highlight for many participants was meeting and getting to know the park staff. It is important to remember that the KNP has not always been accessible to the majority of South African society for much of its existence. During the former apartheid era of South Africa, national parks were not open to all demographic groups. In fact, some people were forcibly removed from within the park boundaries to make way for conservation. As a result, some people feel alienated and separated from the land and resources found within protected areas such as the KNP. For the past few decades, the park has been implementing various projects that aim to restore rights to people, build positive relationships and reconnect people to the land, cultural and natural resources within the park. The mopane worm project is one example of doing just that. Not only did the study show the broader project impacts on participant wellbeing, but also revealed how participation changed how people viewed the park. Harvesters said their relationship with the park was positive and expressed hope for building on this in the future.

Conducting social science research takes time, but it contributes enormous value when assessing the impacts of such projects. The study has shown that when managed effectively, small scale, sustainable resource use projects such as the KNP mopane worm harvest, have the potential to contribute both to human wellbeing as well as conservation. As we move further and further into the Anthropocene, biodiversity needs all the help it can get, and conservation approaches need to be robust and to accommodate a multitude of value systems if these beautiful and valuable places are to persist for our children, and our children’s children. Thinking out of the traditional conservation box is one such mechanism that may just be key for its survival.![]()

Citation:

Swemmer, L.K., R. Landela, P. Mdungasi, S. Midzi, W. Mmatho, H. Mmethi, D. Shibambu. A. Symonds, S. Themba, and W. Twine. 2020. It’s not just about the worm: the social and economic impact of harvesting mopane worms from the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Conservation and Society 18(2): 183 – 199.

Bio:

Dr Louise Swemmer works as a social scientist for South African National Parks, based in Hoedspruit, Limpopo. Louise’s primary professional interest is in promoting fair access to benefits that flow from Protected Areas, both in the interests of justice as well as for the sustainability of conservation.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()