Making your time in Hwange count

At thirteen minutes to midnight, I looked over my shoulder. My blood temperature dropped to match the chilly night in Hwange National Park. There he was, hugely muscled with a big black mane, padding silently, dangerously under the full moon.

The fully-grown male lion stood six metres behind me. I stood, swaddled in a blanket and beanie, in an open-sided hide at Big Toms, not far from Robins Camp. I could hear my heartbeat and feel the adrenaline. But there was no way I was going to call out to my fellow counters, snoring in their roof tents, in case that big boy decided I was worth a closer look.

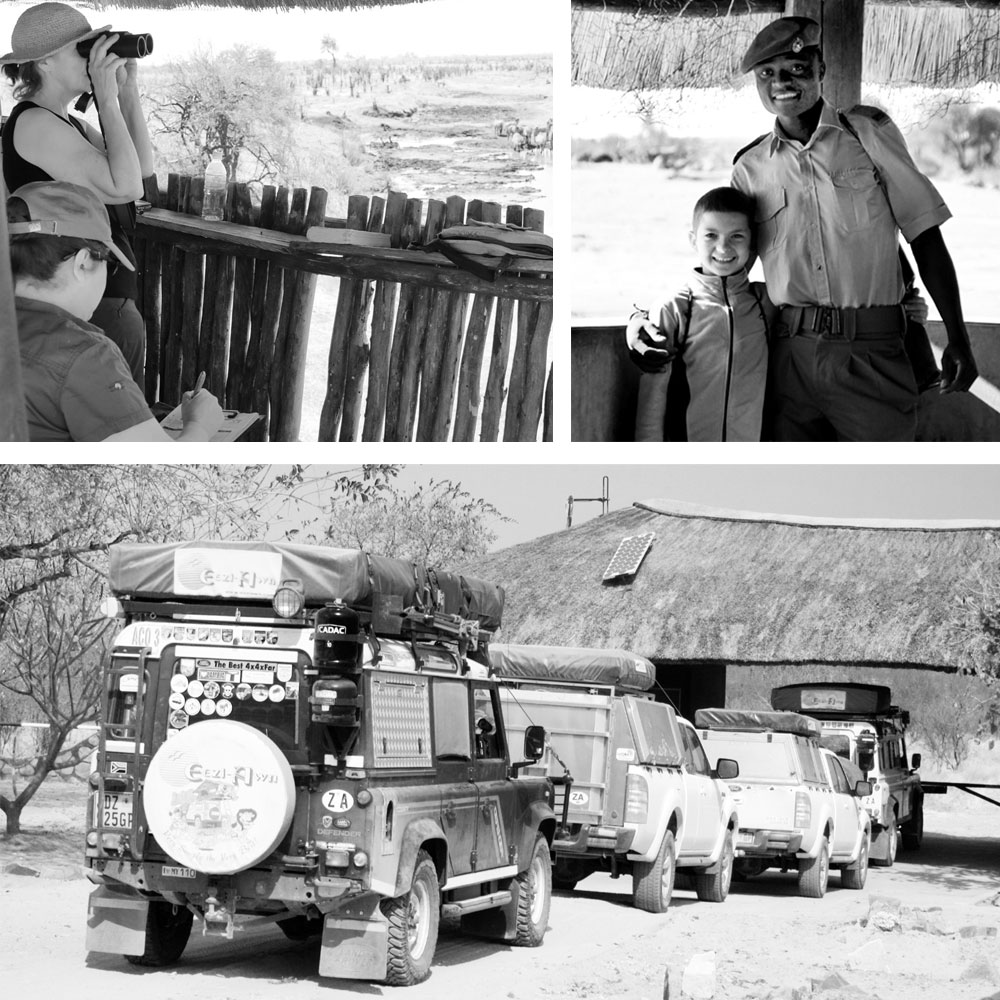

It’s never boring on the Hwange Game Census. This is remarkable in itself, because on ‘the count’ – as it’s better known – teams of volunteers sit as still and as quietly as they can for 24 hours. They must remain silent and motionless from midday to noon the next day over the last full moon of the dry season.

It turns out that when you’re sitting in a hide, or a vehicle in the middle of the bush, just watching and waiting, animals and birds you might otherwise disregard become a reason for great excitement. On quiet counts, I’ve seen people high-five when a herd of impala strolls by.

One thing you can count on

The Hwange Game Census is organised and run by Wildlife and Environment Zimbabwe (WEZ). It is the longest continuously running game census in Southern Africa. Since 1972, through war, drought, boom years and bust, and all of Zimbabwe’s economic and political instability, the count has been one constant in an ever-changing country.

The count covers about 90 pans, dams, hides, natural springs and river pools. For three nights, including the night of the actual census, Hwange is busier than at any other time of year. About 300 WEZ members, all volunteers, take over virtually all the accommodation in Hwange’s three camps: Main Camp, Sinamatella and Robins.

Although its numbers will never be completely accurate, the annual census report, compiled by long-term WEZ member and statistician Foster Betts, makes for fascinating reading. Two crucial things the count identifies are the location of species of interest to researchers and trends within the park.

The most notable trend in the 18 years I’ve been counting is the increasing presence of elephants. Elephant numbers on the count have reached around 30,000 in recent years. And their proportion relative to the total animals counted has risen from between 30 and 40 per cent in the 1980s to 60 per cent or higher.

Other animals’ fortunes wax and wane. Giraffe numbers are down. This is not surprising, given the toll the elephant population takes on trees. However, rarer antelopes such as sable and roan are doing well in Hwange. Buffalo and lion numbers are good. My team counted a herd of 1,000 buffalo last year, and other big herds were seen on this year’s count.

In addition to my moonlit male lion – who conveniently reappeared shortly after dawn so that my fellow counters could get a look at him – we counted giraffe, zebra, reedbuck, sable, warthog, impala, spotted hyena, and black-backed jackal. Two days before the count, I had two separate sightings of wild dogs. And, on the morning after the count, two dogs killed an impala just outside Robins Camp.

Birds aren’t counted during the census, but teams are issued with a bird identification sheet to tick and separate forms to record species that are rare in Hwange. These include ostrich and martial eagle, both of which our team spotted.

Close encounters of the wild kind

The game count is the only time ‘ordinary’ people like me can be out in the park alone after dark. It’s fun, but not for the faint-hearted. First-time counters are usually paired with more experienced volunteers.

I’ve had a lioness run past me just a few metres away as I was boiling a kettle. A bull elephant stuck its trunk through the window of my Land Rover. A curious hyena sniffed at my door as I drank chicken cup-a-soup. And a hungry giraffe mistook my roof tent for a tree.

Counters not in one of the hides usually set up next to their vehicles. They might sit in the shade of an awning during the day, but at night they keep inside their cars unless they answer the call of nature. But sometimes not even that is possible.

As we headed back towards Robins Camp after our count this year, we came across friends who’d been at Little Toms, just down the road. Apparently, they’d also been visited by lions. In the middle of the night, 14 female lions and cubs had decided to lie down to sleep in a circle around their camper. The Hwange game count is not for sissies.

Participate in a game count

Every year, WEZ runs game counts in Hwange, Mana Pools, Gonarezhou, Hippo Pools and Lake Chivero. The counts provide a rough indication of population sizes and indicate whether animals are being disturbed by poachers. Counters also assess vegetation status and water availability. WEZ uses the census information to advise Zimbabwe National Parks on the state of biodiversity and to help set conservation and management priorities.

The game counts are usually done in September, October or December and are open to anyone to participate. For more information about participating in a game count, email mashwild@utande.co.zw.

About Hwange

Hwange National Park is Zimbabwe’s largest national park, covering an area of 14,651km² – approximately half the size of Belgium. The name – mispronounced ‘Wankie’ in colonial times – comes from a local chief. In the early 19th Century, the area was the royal hunting grounds of the Ndebele warrior-king Mzilikazi. Later, settlers tried to farm and breed cattle there but were deterred by the lack of water and the abundance of tsetse flies and predators. It was set aside as a game reserve in 1928 and proclaimed a national park in 1961.

Although it has virtually no natural water sources (water must be pumped in), Hwange is a haven for over 100 mammal and 400 bird species. There are more than 20,000 elephants in the park, and it protects what is thought to be one of the largest populations of African wild dogs. Large prides of lion and buffalo are frequently seen there, and you also have a good chance of spotting leopard, as well as cheetah and spotted hyena. The wild and woolly brown hyena occurs here, too, but is rather rare.

About the author

Bestselling author Tony Park first visited southern Africa 21 years ago as a tourist on a once-in-a-lifetime holiday. That first safari turned out to be anything but. After returning every year since 1995, he and his wife, Nicola, put down roots in South Africa four years ago, buying a house in a game reserve on the edge of the Kruger National Park. The former journalist, public relations and army officer (he served in Afghanistan in 2002), now spends six months of the year in his native Australia and the balance in Africa, where he researches and writes his thriller novels.

In this edition, Tony talks about his personal experiences in Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park, including the annual game census in the park, which Tony and Nicola have taken part in for the past 17 years.

Several of Tony’s novels, including Far Horizon, African Dawn and Safari, are set in Hwange, and they reflect his love for troubled Zimbabwe and its flagship game reserve. Tony’s African novels have a strong environmental bent. His 13th and latest book, Red Earth, set in KwaZulu-Natal, focuses on the plight of Africa’s endangered vultures. Read more at www.tonypark.net

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()