Reflections from the Great Lakes of East Africa

In early 2018, I set out to journey across the three largest of the African Great Lakes: Lake Malawi, Lake Tanganyika, and Lake Victoria. My objective was to traverse the region by “fair means”: solo, self-sufficient, and entirely human-powered. I would start in the south, and make my away across the lakes via kayak, paddling each day and coming to shore each night to sleep, while between lakes I would travel by bicycle. Without engines and guides, I would have no choice but to embrace the landscape and its people without any degree of separation. And, if I succeeded, it would be in a style that I could be proud of.

My journey through the Great Lakes of Africa began as a student in the research lab of the University of Colorado, as we explored inhabitants of Lake Tanganyika. I quickly discovered that the Great Lakes has a massive impact on global biodiversity, as well as the lives of millions of people who call the region home. This formed a seed of inspiration for me to gain a more ‘hands-on’ research experience alongside local nature conservancy the Tuungane Project.

I designed this expedition to be the purest and most challenging form of expedition travel. I planned to enchain the African Great Lakes by human power – kayaking each lake and bicycling in between – without a support team, solo, and carrying all of my equipment along with me. In that way, by exposing myself to the insecurities of being alone and the rigours of human-powered travel, I would strip down the expedition to its purest elements.

I knew that a trip of this scale, with this level of commitment, is something that shouldn’t be entered into lightly. The most important thing that I needed to do to succeed on the trip and remain safe was to prepare sufficiently, but that preparation comes in myriad forms. For me, this expedition was the culmination of years of preparation: studying the region in university, sharpening my wilderness survival skills in the Amazon, educating myself on tropical diseases, spending time in Africa becoming acclimated to the culture and learning about dangerous animals and how to avoid them, mastered the use of my field equipment, and countless days spent on the water. This expedition was something that I had aspired to for a long time, but I only decided to move forward with it once I thought that I was sufficiently prepared.

That said, I also needed to do significant research into the different areas, routes, and potential problems that could present themselves along the way. Even things as banal as border crossing procedures aren’t necessarily so straightforward when you intend to cross the border on water. I spent months online researching topics from crocodile attacks to weather patterns. Where possible, I also reached out to people who could provide information, such as lodge owners and NGO workers, and they were very generous with their time.

My Journey

A trip like this isn’t for the faint of heart. Risk comes with the territory, but if I was going to succeed in this endeavour, I needed to be an expert in my craft, trust my instincts, and remain hyper-aware throughout the trip. All of these things are significantly magnified by being alone. At a baseline, I was certainly more at risk when alone and had fewer options for recourse if things do go wrong, but perhaps more challenging is the psychological aspect of spending months making decisions that have significant consequences, and then dealing with the endless internal monologue that is second-guessing each decision. There’s no comforting consensus when you are alone, and it takes a certain amount of resolve to be able to, or willing to, push through the excruciating loneliness and isolation.

When I would arrive in a village, I would immediately be greeted by a crowd of curious onlookers. The thing is that wherever you go in the world, people are people. Connecting on a human level, even when there was a language barrier, was relatively effortless.

Every community extended to me great warmth and welcoming, despite virtually all of the communities experiencing the daily struggle to a certain extent. Poverty is a great challenge through the entire region, and yet it didn’t impede the kindness that I experienced in every village.

Camping alone, however, was slightly concerning, and in general, I didn’t like to camp near people without speaking to them. That is to say, I only ‘bush’ camped when there was no one around, and no one knew of my presence. If that opportunity didn’t present itself, then I would go into a community and introduce myself and ask if it was alright for me to spend the night there.

By declaring my presence and asking for permission, I felt as though I belonged, even if only for the one night.

That said, no expedition like this is without significant danger. On the third day, while paddling north along the shoreline of Lake Malawi, I heard a splashing sound from the water. When I turned to look, I saw that a four or 5-metre crocodile had surfaced and was staring at me icily before it disappeared back under the surface. After that, I took even greater precautions to avoid crocodiles – paddling several kilometres offshore, avoiding river mouths and wetlands, and staying away from the water at night, and I was mostly able to neutralise that threat.

Still, I looked over my shoulder every few minutes for the remaining months of the trip, hoping that I wouldn’t find a large predatory reptile behind me.

Conservation and Sustainability

During my trip, I realised that the main issues are overfishing, unsustainable fishing practices, unsustainable agricultural practices such as bush charcoal production and steep hillside agriculture which lead to significant sediment inputs into the lake, climate change, and introduction of invasive species. The local human impacts, such as fishing pressures and agriculture, are particularly compounded by rapid population growth in the region.

Despite this, communities are very receptive to learning about sustainability. The local people understand that fish populations are decreasing over time, and they are hungry for education that can empower them to protect their resources.

I spoke with many fishermen and farmers who stated exactly this and voiced their understanding that these resources need to be protected so that they will continue to provide for local people well into the future.

At the same time, some of these people are barely getting by, so alternative means of producing income is essential. When people are desperate, they are going to do whatever they have to do to survive, even if it’s a short-term gain that has significant long-term consequences. There also needs to be enforcement of fishing regulations, whether it’s conducted by the government or by a local community group such as the Beach Management Units, so that a few bad actors don’t damage the shared resource.

What the Tuungane Project is trying to do is to educate and foster growth in sustainable means of agricultural production and fish yields, alternative income, and grassroots enforcement of fishing regulations. They’re also working with Pathfinder International, another NGO, to improve family planning education and access to birth control, which will allow women to decide how many children they want to have and may reduce population growth. All of these working in conjunction is the only way forward.

Looking to the Future

I want to continue to be an ambassador for The Great Lakes region and continue to promote conservation initiatives. I think that the most pressing issue we need to consider is population growth, which leads to an increase in consumption and a correspondingly bigger footprint. More people will need more fish, which produce more plastic and turn more forests into agricultural lands, and so on.

But population growth is only experienced for a while; then it tends to level off, especially when people are empowered with knowledge of family planning and have access to birth control. So, I think that it’s essential that people get out there and help to educate others on sustainable behaviours so that the environment can be preserved.![]()

About the African Great Lakes

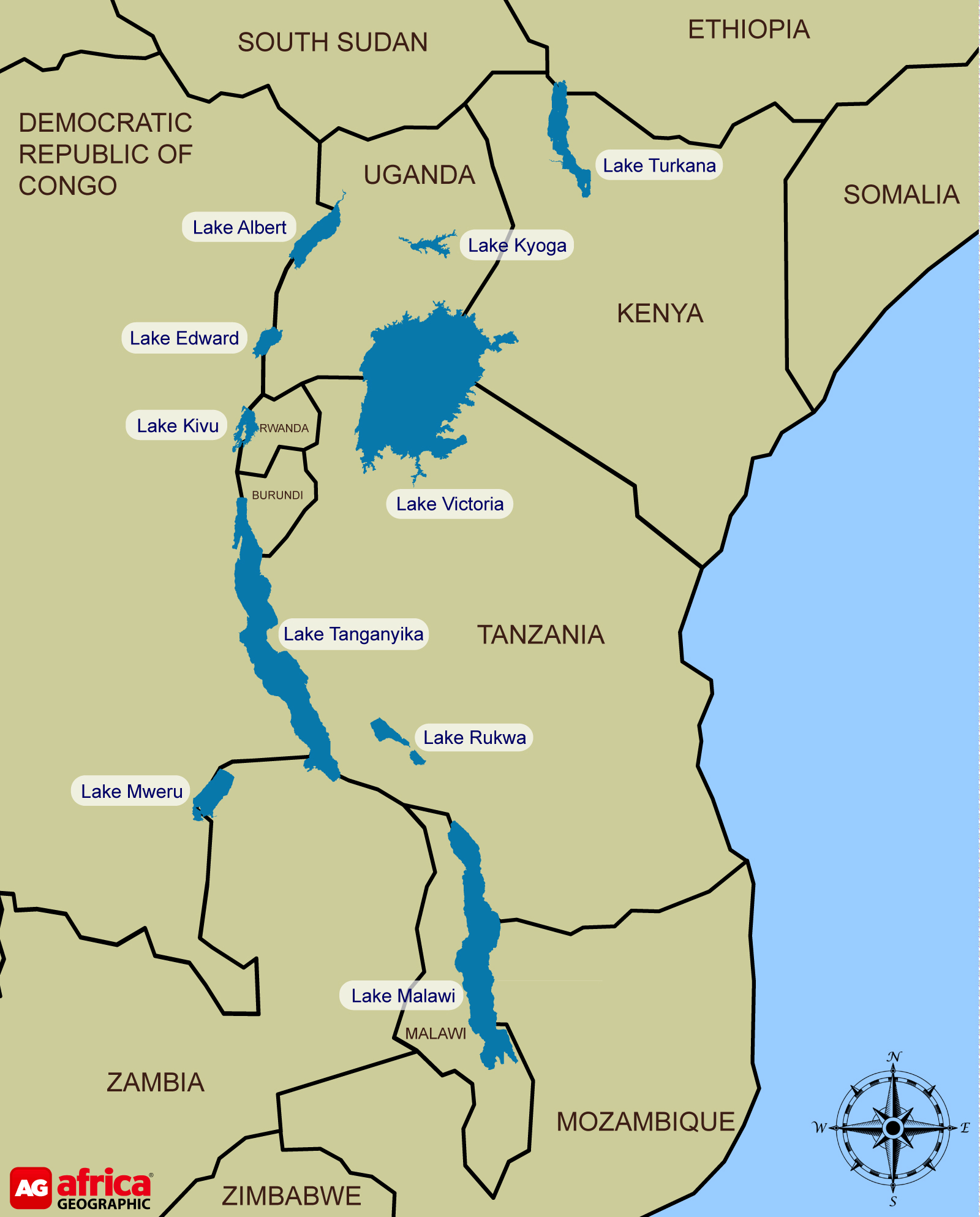

The African Great Lakes are a series of lakes that make up part of the Great Rift Valley lakes in East Africa. The lakes hold approximately 27% of the world’s fresh water and 10% of the world’s fish species.

The major African Great Lakes include Lake Victoria (26,563 sq mi), Lake Tanganyika (12,355 sq mi), Lake Malawi (11,428 sq mi), Lake Turkana (2,472 sq mi) and Lake Albert (2,046 sq mi). There are other smaller lakes in the region which include Lake Edward (977 sq mi), Lake Kivu (857 sq mi), Lake Mweru (1977 sq mi), and Lake Rukwa (759 sq mi). They are classified based on river basins, the presence of a draining river or its absence, and the size of the lake.

The exact number of lakes considered part of the African Great Lakes varies by list, and may include smaller lakes in the rift valleys, especially if they are part of the same drainage basin as the larger lakes, such as Lake Kyoga that is part of the Great Lakes system but is not itself considered a Great Lake, based on its size of 660 sq mi.

The three Great Lakes that Ross Exler traversed were Lake Tanganyika, the second largest lake in the world by volume, the second deepest lake, and the longest lake in the world; Lake Victoria, the second largest lake in the world by surface area; and Lake Malawi, thought to have the most species of fish of any lake in the world and is the fourth-largest by volume.

The Great Lakes region comprises of Burundi, Rwanda, northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, and northwestern Kenya and Tanzania – the areas lying between northern Lake Tanganyika, western Lake Victoria, and lakes Kivu, Edward and Albert. The term ‘ Great Lakes region’ is used in a broader sense to extend to all of Kenya and Tanzania, but not usually as far south as Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique nor as far north as Ethiopia, though these four countries border one of the Great Lakes.

An estimated 107 million people live in the Great Lakes region and depend almost exclusively on natural resources for their livelihoods – the lakes being a significant source of food, water and income. Overpopulation is now competing for the habitat used by many endangered species, including the mountain gorilla and the forest elephant. Resources have already deteriorated due to unchecked or unregulated exploitation, invasive species, habitat degradation, pollution, and eutrophication, though governments in the region are attempting to lessen the impact through integrated conservation and development projects

Development and conservation of the lakes and their basins are complicated by the fact that they are shared by more than one country, with actions often being implemented at national levels in the absence of regional institutions to coordinate and harmonise efforts among countries.

Even those lakes with regional authorities, such as Lake Tanganyika Authority or Lake Victoria Basin Commission, struggle to implement lake management programs due to limited access to funding mechanisms and limited to no enforcement powers.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, Ross Exler

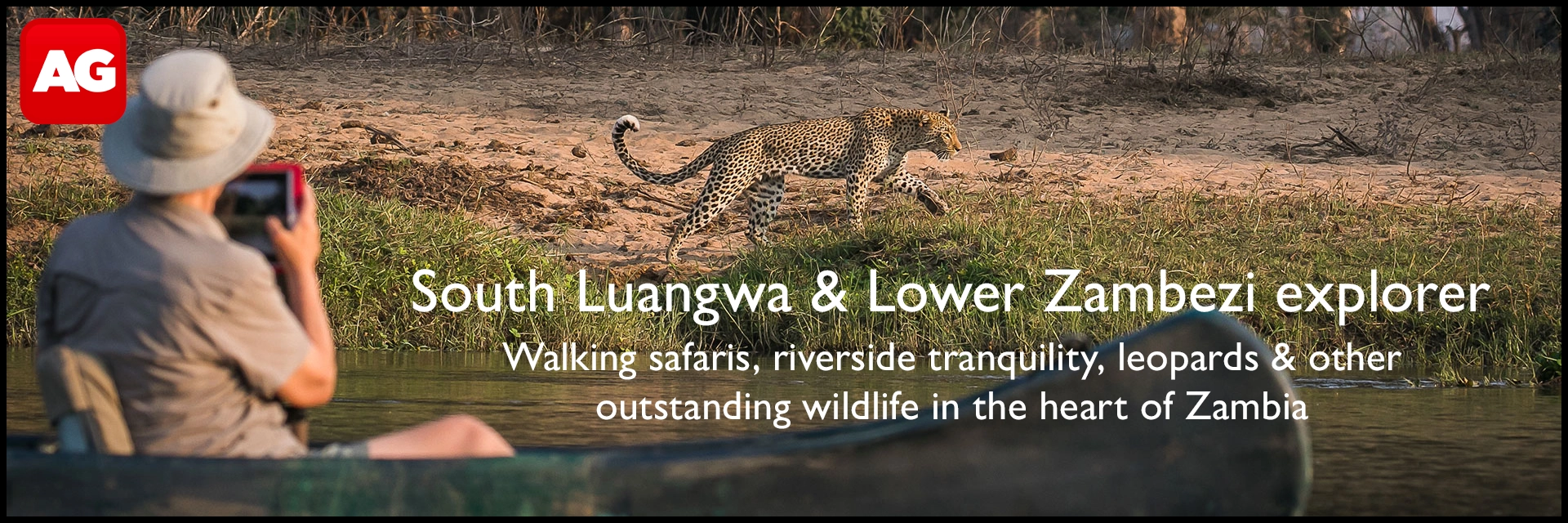

Ross Exler is an ambitious world adventurer, passionate about biodiversity and the sustainability of ecosystems in Africa. So much so, he decided to embark on a journey to become the first person to complete a solo, man-powered crossing of the African Great Lakes. His aim? To understand more about sustainability, conservation and the balance between humans and the environment.

Ross’s choice of man-powered transportation when crossing these natural wonders reflects the necessity for humans to power real environmental change in and around Lake Malawi, Lake Victoria and Lake Tanganyika. To read more about his journey through the Great Lakes of Africa, click here.

ALSO IN THIS WEEK’S ISSUE

Maasai Mara Specialist Photographic Safari

This is possibly the most exciting photographic safari to Kenya’s Maasai Mara that we have seen in a while. Award-winning photographer Arnfinn Johansen will host four lucky Africa Geographic guests for nine days / eight nights, making use of a specially-adapted vehicle and an off-road driving permit to secure epic wildlife images.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()