Photographic celebration of this diversity hotspot

Central Mozambique is a place in constant flux: fire and rain, conflict and peace, absence, and abundance. But in the middle of it all sits the unmoving fulcrum of Gorongosa National Park, tirelessly protecting one of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet. I was able to spend a few years documenting and living its story.

I landed in Gorongosa National Park, fresh out of graduate school in 2016 as a biologist-turned-cinematographer and was immediately thrown right into the middle of things – filming wildlife on safari. My job was to track and film the nature and conservation stories that would endlessly blossom around the park. It was my first time on the continent, my first time living so far from home, and my first experience filming some of the world’s most dangerous animals in such close proximity.

Gorongosa National Park was proclaimed in 1960. The historical section covers an area of 3,719 km² (371,900 hectares), and the buffer zone around the park increases the total size of the protected area to 9,419 km² (941,900 hectares). The Gorongosa Mountain was proclaimed as a protected area in 2010.

Just as soon as the war for independence ended, civil war erupted in 1977 and continued for decades before it finally ended in 1992. In the centre of the country, Gorongosa National Park became embroiled in the heart of the conflict. The park’s wildlife became a resource for the fighters: bushmeat filled bellies and ivory lined pockets and paid for weapons. 90% of the region’s large mammal species vanished.

The park languished for nearly twelve years until the Gorongosa Restoration Project was formed in a partnership between the Mozambican government and philanthropist Greg Carr – a project intended to breathe life back into the landscape. The goal of restoring the park to its former ecological glory was an ambitious one, but it is one that has seen hard-won progress since the project’s inception.

When I arrived in Gorongosa, the process of recovery had been underway for nearly a decade. My first impression was similar to that of many visitors: the park was an antelope Eden. By then, their numbers had returned to pre-war levels. As the most abundant antelope species, waterbuck numbers had reached over 55,000 (more than 10 times as many as during the war), and they dotted the landscape like a southern Serengeti.

Beyond the vast antelope populations, there’s a kaleidoscope of unique life. Rainforests, savannas, grasslands, and even limestone gorges support a cast of characters from the tiny (like the pygmy chameleons found nowhere else on earth) to the gigantic.

I spent days roaming the park in a specialised open Land Cruiser that had been modified for filming. Each day was a treasure hunt – searching for wildlife and showcasing fascinating behaviour, and chasing the perfect light and composition. One of the more common hazards was the herds of elephants. Being highly intelligent, many individuals carried physical and emotional wounds from the war.

My job entailed more than just filming natural history – it was more about telling the stories of how human and animal lives overlap, documenting the people living and working in and around the park. Stories of scientists, conservationists, veterinarians, rangers, health care workers, and the many communities outside the park.

A hands-on approach to recovery has been guided by the restoration efforts of a team of conservationists and biodiversity scientists. They monitor populations and habitats to strategise ways to build complexity into the web of life while maintaining stability for the park’s ecosystem.

Gorongosa is an entirely different place from the air – a perspective that reveals its true vastness. Watching masses of slithering crocodiles and snorting hippos from an open-door helicopter was one of my favourite moments, as was going on anti-poaching patrols with Alfredo Matavele, the pilot of the park’s Bat Hawk light aircraft.

Tensions between humans and wildlife were particularly high when I arrived, and illegal hunting was commonplace. I spent much of my time with the Carnivore Conservation Team. The above image shows tireless conservationist Paola Bouley in front of the funeral pyre of M02 – one of the park’s lions. Paola is holding the GPS collar that had been used for monitoring the lion’s movements. Like many other lions, M02 was killed by a poacher’s gin-trap – an accidental death caused by indiscriminate poaching.

There have been people living in this area for thousands of years; they are part of the ecosystem, defining it with their actions. There are currently nearly 200,000 people living in the park’s buffer zone – the area between the park and the surrounding communities. As is the case throughout rural Mozambique, poverty levels are extremely high, and bushmeat poaching is tempting because meat is expensive, and protein shortages are common.

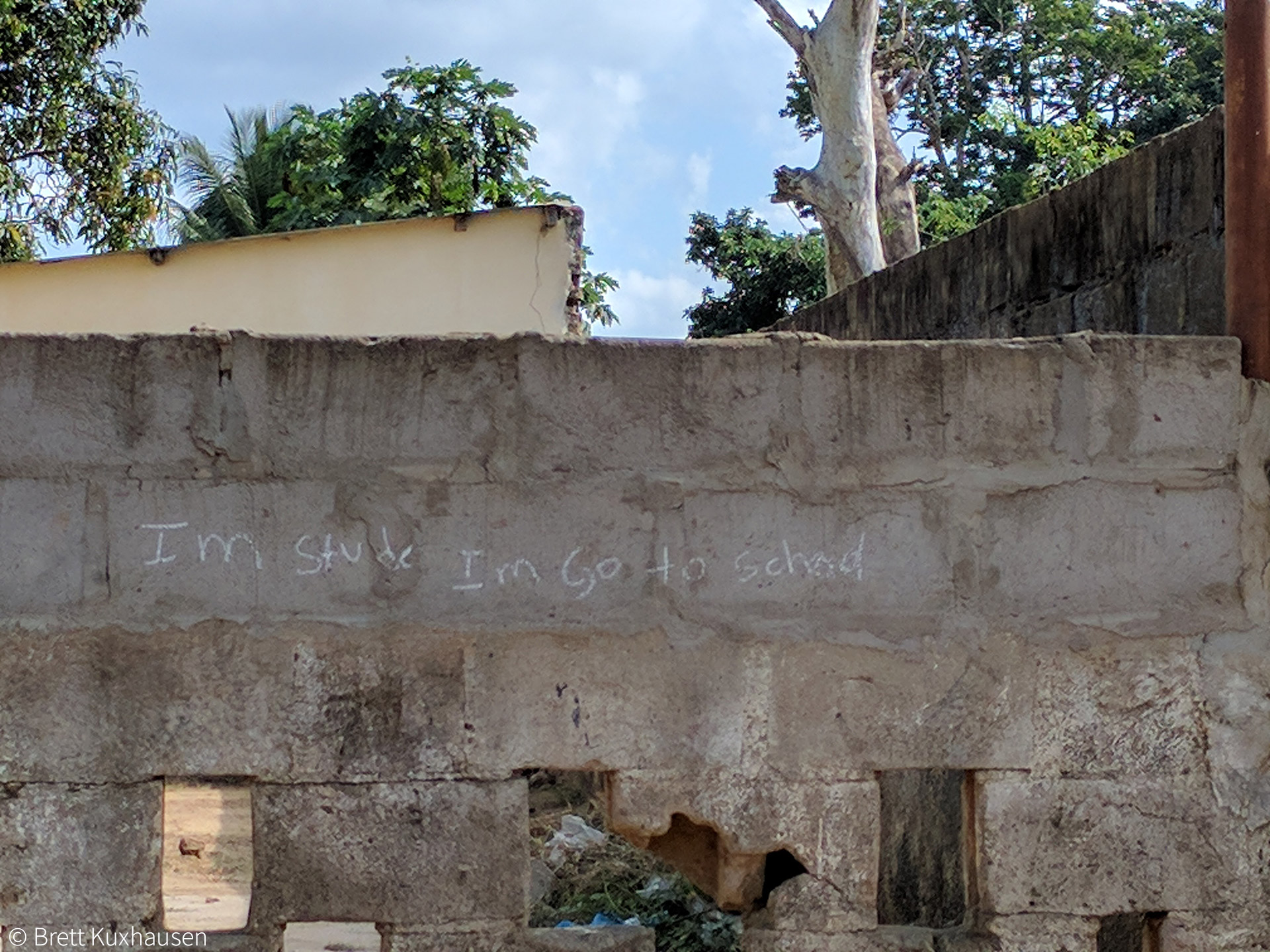

Women are the most vulnerable to the effects of poverty. They are the backbone of this rural economy, but are disproportionately affected compared to men, especially when young. Child marriage, unwanted pregnancy, illiteracy and HIV are all pressing issues.

Towering high over these lives is Mount Gorongosa – the beating heart of the region, looking out for miles over the southern end of the Great Rift Valley. Lush forests along its slopes capture moisture floating in from the Indian Ocean that then feeds the arterial rivers below. Since 1970, nearly 40% of these forests have been lost to deforestation. It has also been the site of low-level insurgency in recent years.

In the modern home in the developed world, one barely thinks twice of the seemingly endless supply of clean water. In Gorongosa, the community members devote hours of their time to collecting it. Most have no electricity or indoor plumbing, and women and children spend much of the day filling up containers for their family at community wells.

A substantial wet season is critical not just for the park’s habitats but for farmers’ crops in the buffer zone. There have been instances of severe drought through the years, and in 2019, Cyclone Idai hit the area. This was one of the worst weather-related natural disasters that the southern hemisphere has ever experienced: 200,000 people were made homeless, and 2 million acres of crops were destroyed.

Even in an ideal year, with a good harvest and favourable weather, there is the inevitable unpredictability in living next door to a national park. Dona Maria (pictured above) lost her leg to a crocodile while bathing a few years ago and is regularly chased out of her home when elephants raid her crops at night.

Fencing the park boundary is not a feasible solution for an area that covers a million acres. The lives of both humans and animals are balanced on a razor’s edge, and the tenuous line between the park and the buffer zone must be protected for the sake of both.

The park approaches these challenges with a community-based conservation method. On the front lines are the Rangers, the park’s law enforcement unit of Mozambicans tasked with helping maintain coexistence.

Rangers are usually locals, tasked with bridging the gap of understanding between their own communities and the wildlife. In the above image, a local leader (far left) presides over a traditional ceremony to bless the translocation of a brown hyena into the park. The hyena had been killing chickens, goats and even dogs on community land, but the community reached out to the park instead of taking drastic action.

To many in Mozambique, the capture of a pangolin is considered to be good luck, though Rangers are working to change these views in the buffer zone. During the first half of 2019, 13 trafficked pangolins were rescued by Gorongosa park rangers and cared for by veterinarians.

The park is working on finding ways to alleviate poverty through creating human development programs that focus on improving the quality of life. Mãe Zerina (pictured above) is a Traditional Birth Attendant. She is 80 years old and spends most of her time accompanying pregnant women from her community to the nearest hospital for health check-ups, family planning and births.

Signs of hope are everywhere for those who know where to look. Girls Club is a before-and-after-school programme started by the park to teach essential life skills to empower young girls to stay in school and learn about personal safety, health, nutrition, and family planning. The club also takes the girls into the park, and for many, this is their first opportunity to see wild animals.

To me, the most tangible sign of the park’s success has been the reduction of snaring. Teams sweep an area to find and remove snares, creating safe zones for the larger animals.

Lions were the only large carnivore present during the park’s restoration. Now, with the lion population safe, a pack of 14 African painted wolves (wild dogs) have been reintroduced. Filming their reintroduction was my favourite project, and I spent innumerable hours with them, getting to know their unique characteristics: Beira the stoic alpha female, Minimini the young upstart, Ndarassica the trickster…

My work over the years was focused towards creating long-form documentaries rather than filming wildlife on safari, often specifically for Mozambicans to be broadcast on national television. Even in the buffer zone, cinema finds a way, and small movie-huts play DVDs for an enthralled audience. There is also a community outreach team that organises public screenings of park media. The look of amazement on these faces makes my job worthwhile. It gives these kids a chance to understand and connect with their home in a way they might not otherwise experience – and gives them something to aspire to.

Not many people get lucky enough to live with iconic wildlife and tell the daily stories of the people doing what it takes for conservation to succeed. It was an experience that was sometimes frustrating, at times funny, and always rewarding. Even better, during my last year in Gorongosa, a litter of 18 painted wolf puppies was born, and I was there to watch them grow up.

About Brett

Brett is a filmmaker and photographer who documents global wildlife, science, and conservation stories that inform and inspire action. A recovering biologist from the heartland of the United States, Brett embedded for nearly four years in Mozambique’s flagship conservation area, Gorongosa National Park. In his time there, he helped create multiple award-winning films that can be seen on PBS, National Geographic, and Mozambique television. His photography of the park has been featured in outlets such as The New York Times, The Guardian, The Associated Press, and Nature scientific journal.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()