Africa's bleeding-heart monkey

There are many wonders to behold from the Roof of Africa in Ethiopia. Here in the Highlands, at altitudes over 3,000 metres, a rare goat leaps nimbly between rocks and the continent’s most endangered carnivore – the Ethiopian wolf – stalks through the heather, searching for mole-rats. But of all the weird and wonderful creatures on display, the gelada is unequivocally the star of the show.

Gorgeous geladas

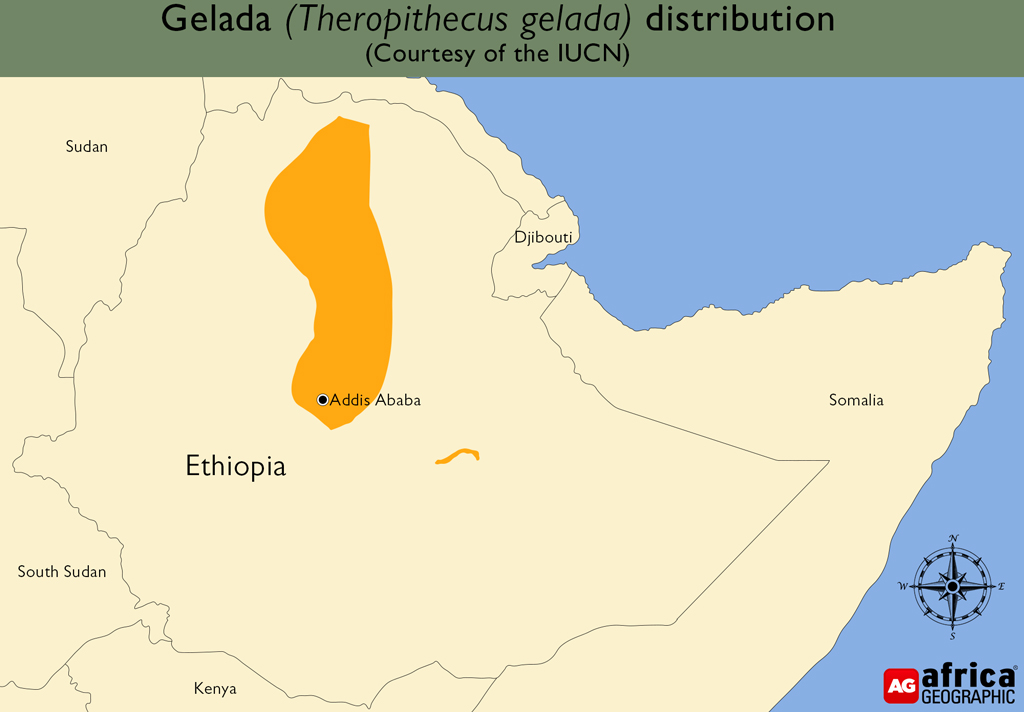

Geladas (Theropithecus gelada) are a species of monkey endemic to the Highlands of Ethiopia, occurring only at altitudes between 1,800 and 4,400 metres above sea level. They are highly social graminivores (grazers) and, given the distinct lack of large trees at their preferred altitude, are the least arboreal primates after humans. They spend their days foraging the plateau’s grasslands before descending to the surrounding cliff faces to pass the night in (relative) safety on narrow ledges.

Astonishingly for an animal so extravagantly adorned with bright colours and coiffed fur, it is only in the past two decades that the gelada has experienced something of a surge in tourist and scientific interest. This is mainly due to Ethiopia’s troubled history, as famine, political turmoil, and civil war laid waste to the country and her people and put paid to any hopes of a burgeoning tourism industry. As the country stabilised, visitors returned to explore a land steeped in history and scenic beauty – and quickly discovered the magic of the geladas.

And, as it turned out, geladas are naturals when it comes to entertaining fascinated tourists and eager photographers. They have an almost uncanny ability to strike a pose, invariably against a backdrop of jaw-dropping scenery. Their bright red, hourglass-shaped chest patches stand out against the muted greens and browns of their habitat, and the thick blonde manes of the males are positively leonine. Geladas also proved to be quick to habituate (like many primate species), allowing visitors the intimate opportunity to observe their social lives. (As we can never resist the opportunity to highlight this, check out this post depicting Africa Geographic travel director Christian Boix’s encounter with a very forward gelada.) Geladas are intelligent and live in exceptionally complex, multilevel societies, so their day-to-day interactions are guaranteed to captivate and enthral onlookers.

Quick facts

| Length: | 50-75cm |

| Mass: | Males (average): 18.5kg |

| Females (average): 11kg | |

| Social Structure: | Reproductive units, bands and herds |

| Gestation: | Around six months (approximately 180 days) |

| Conservation status: | Least concern (for now) |

The gelada baboon? No.

The gelada is frequently referred to as a ‘gelada baboon’ – an understandable but incorrect moniker. At first glance, baboons and geladas share several morphological similarities, including basic body and head shapes. The exact phylogenetic relationships between the baboons (Papio spp.), mandrills and drills (Mandrillus spp.), mangabeys (Lophocebus spp. and Cercocebus spp.) and geladas (Theropithecus) have been subject to considerable debate and several changes. However, the most recent genetic studies indicate that baboons and Lophocebus mangabeys are more closely related, and geladas are an evolutionary outgroup. While it is undoubtedly true that common names of animals do not always reflect their exact biological family (think koala bear), using appropriate terminology can help prevent confusion. [For an entertaining, subtle rebuke of scientists referring to geladas as ‘gelada baboons’ – and some clarity on this subject – you can read What is (not) a baboon?]

The gelada is the only surviving member of its genus, though fossil records show that there were once at least three larger geladas spread across Africa and much of Asia. Today, there are two recognised subspecies: the northern gelada (T. g. gelada) and the southern gelada (T. g. obscurus), which is also known as the eastern or Heuglin’s gelada.

Gregarious gelada

If geladan taxonomy was tricky, then their social structure is downright Daedalian. Let’s start with the basics: the fundamental building block of gelada society consists of a small group (two to 12) related females, their babies and a couple of (usually unrelated) mature males. These are called “reproductive units”. The next step up the gelada social pyramid is “bands” – groups of between two to 27 reproductive units. Bands usually share overlapping home ranges with around three other bands, which form a “community”. Finally, there are “herds”: temporary aggregations of over sixty reproductive units (potentially over 1,000 geladas). With us so far? Good, because there’s more.

Within each reproductive unit, the females coexist in a hierarchy, with the more dominant members demonstrating greater reproductive success. The males within the reproductive unit curry favour with the females, often showing a distinct preference for one or two individuals and reinforcing existing bonds through grooming. This diligent approach to caregiving may serve the males well in the event of an aggressive takeover attempt by another male. Though considerably smaller than the males, the females yield formidable power in the unit and may choose to support or abandon a male depending on his contribution.

While females tend to stay within their natal reproductive units for life, young males generally have to strike out on their own once they reach sexual maturity. They form small groups of all-male units and wait for the opportunity to join (or take over) a reproductive unit.

The complexities of gelada societies abound and would occupy several pages if described in full. Scientists are still unravelling fascinating nuggets of information about cheating partners, spontaneous abortions and “contagious” yawns.

Garrulous gelada

These intricate social niceties require considerable communicative abilities. Naturally, body language cues play a central role in gelada intercourse. Perhaps the most famous of these signs is the infamous “lip flip”, where the upper lip is folded upwards over the nostrils, exposing a terrifying set of canine teeth. This is combined with a raised brow, exposing pale rings around the eyes. The message is unambiguous: “If you come closer/do that again/ do not move, I will bite you.” It can be used in aggressive displays or by a defensive animal attempting to submit.

However, geladas are not limited to games of charades to convey their message. They talk to each other. Constantly. So much so that some scientists believe that gelada chattering is about as close to human speech as any primate comes. They mutter and lip-smack and can communicate reassurance, appeasement, respect, appreciation, anger, and aggression.

Sitting pretty

Geladas occupy an extreme habitat at high altitudes, and this comes with certain advantages, including a dearth of competition and predators. Leopards, hyenas, servals and birds of prey all hunt geladas, but they are few and far between in the Highlands and living in groups means that there are plenty of eyes to watch for potential problems. So successful is this approach that over 85% of all infant geladas survive to adulthood – a remarkably high number in the wild. Interestingly, Ethiopian wolves pay them no heed and will often wander into the midst of a herd without any reaction from the grazing primates.

However, living the high life means that nutritious food is hard to find, and geladas have to spend most of their day foraging. 90% of their diet consists of grass; only a fraction is supplemented with seeds, flowers and the odd insect. They are the only primate species to follow this strict dietary approach. Their constant need to feed means that geladas adopt a specialised shuffle gait to move from grass to grass and spend most of their lives on their bottoms. They even have special fatty pads to act as built-in cushions.

Most “Old World” (Cercopithecidae) monkeys display their reproductive status through bright colouration, unambiguously positioned around the genitals and perineum. In the case of geladas, however, the traditional sexual signalling device is hidden from view most of the time, hence the chest patch, which changes colour and texture depending on hormone levels. The chest patches of females in oestrus become bright red and break out into a “necklace” of fluid-filled blisters. If this primate decolletage fails to spark the interest of her preferred male, she will simply position her rump under his nose until he gets the message.

Life on the edge of a cliff

A shortage of nutrients also makes geladas something of a crop pest. Popular with tourists though geladas may be, farmers take a far less welcoming view of roaming herds raiding their barley fields. One study showed that each animal causes approximately 100kg of crop damage. This conflict with people (especially in a country where food shortages are rife) and its inextricable link with extensive habitat loss is believed to have resulted in a loss of around 50% of Ethiopia’s gelada population over the past half a century. The gelada is listed on the IUCN Red List as “Least Concern”, but their numbers are believed to be declining.

Fortunately, there are protected areas where geladas continue to flourish. Simien Mountains National Park is home to Ethiopia’s largest population and offers some of the best gelada viewing in the country.

Get in touch with our travel team to help arrange your gelada experience – details below this story.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()