KINGSLEY HOLGATE'S AFRIKA ODYSSEY EXPEDITION

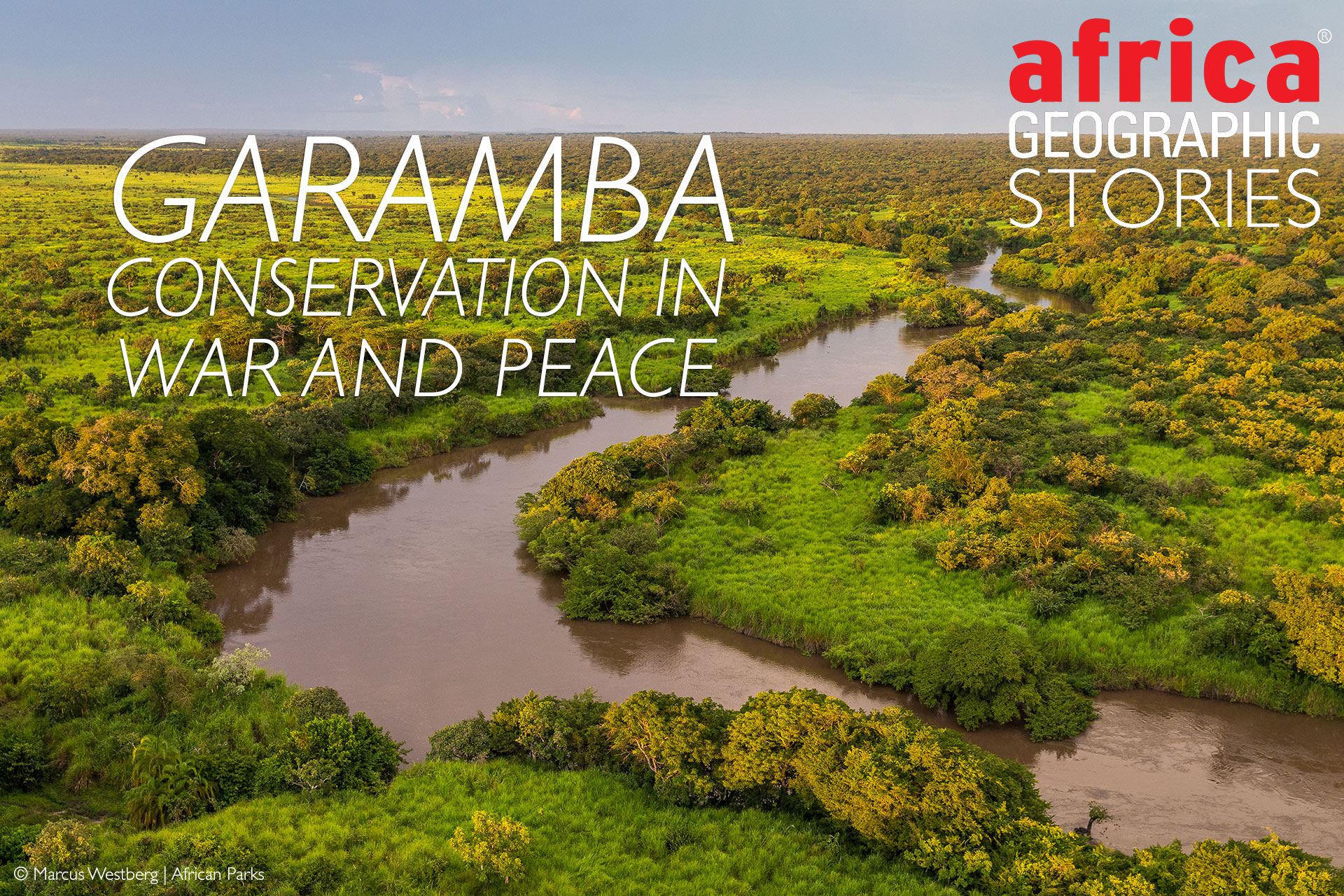

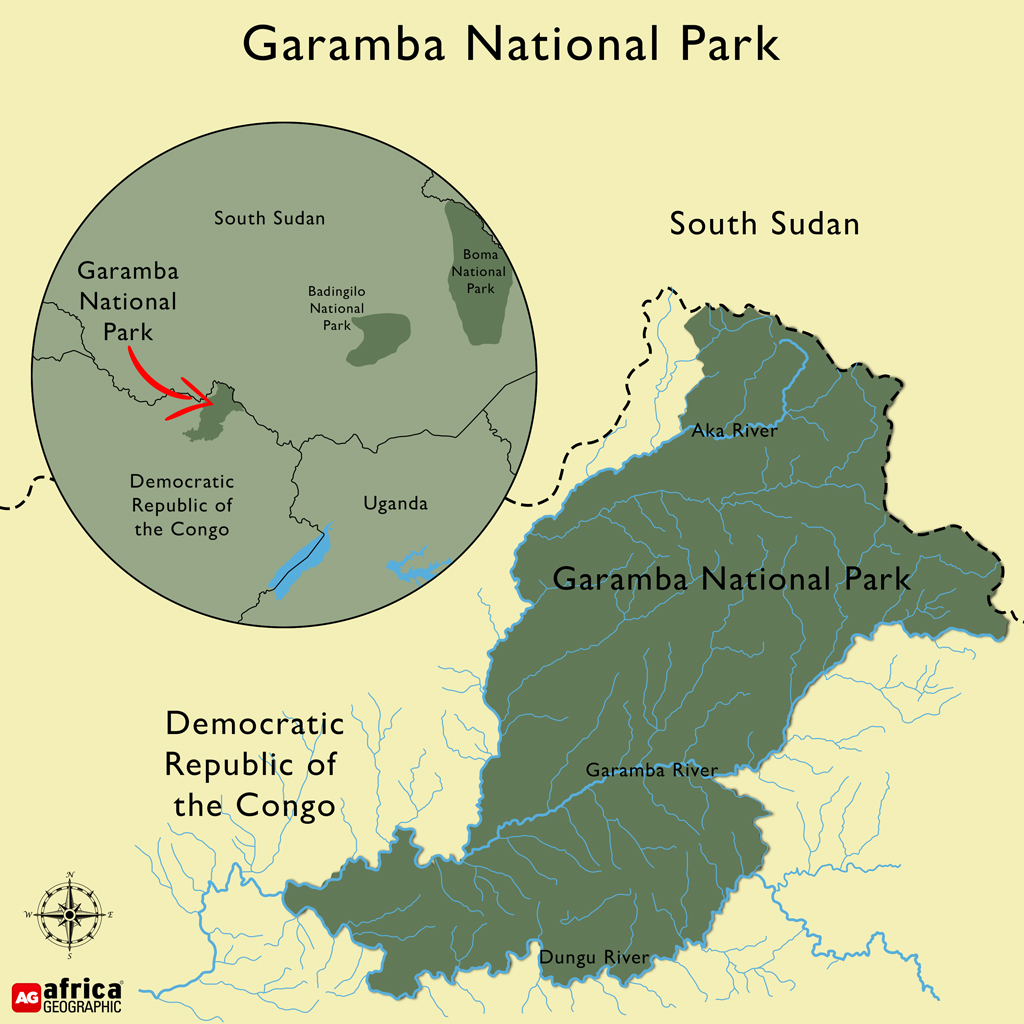

Over many years, around countless campfires, we’ve dreamed of reaching Parc National de la Garamba. This vast, remote wildlife sanctuary is in almost the exact centre of the African continent, tucked into the northeast corner of the Democratic Republic of Congo, with Uganda to the east and the CAR and South Sudan to the north.

Renowned African explorer Kingsley Holgate and his expedition team from the Kingsley Holgate Foundation recently set off on the Afrika Odyssey expedition – an 18-month journey through 12 African countries to connect 22 national parks managed by African Parks. The expedition’s journey of purpose is to raise awareness about conservation, highlight the importance of national parks and the work done by African Parks, and provide support to local communities. Follow the journey: see stories and more info from the Afrika Odyssey expedition here.

Made up of an open savannah and surrounded by dense equatorial rainforests, Garamba is the third-oldest national park in Africa, proclaimed in 1938. But like much of the DRC’s ravaged past, the park has endured decades of civil war, armed conflict, rampant poaching, and tragic loss of human life. For years, it’s been virtually unreachable for adventurers like us. Finally, the opportunity is here.

But our previous overland and river journeys in the DRC have been anything but easy. So, it’s with a gnawing, rat-in-the-stomach feeling that we leave Rwanda’s Akagera and Nyungwe National Parks and head for ‘La Garamba‘ – number 13 of this journey to showcase stories of hope from 22 African Parks-managed wildlife areas across the continent.

Garamba, here we come

Trekking across Uganda, the expedition Defenders make short work of summer storms and flooded muddy tracks, and we throw out our tents at the Murchison Falls Lodge campsite to a great ‘welcome back!’ from manager Paul and staff. It’s a memory lane experience; upstream, the mighty Nile compresses into the 10-meter-wide Murchison Falls, where giant crocs feed on fish stunned by the turbulence. Watching the churning fury flowing westward into Lake Albert, we can’t help but think of the trickle we saw seeping out of Nyungwe’s high plateau just a few weeks ago, which marks the furthest source of the Nile – and here we are again, on the banks of the world’s longest and most historic river.

As we pore over well-thumbed maps in search of a route-less-travelled to reach the Arua border with the DRC, a friendly staffer asks, “Why don’t you take the ferry across the lake to Panyimur?” Now, that sounds like an adventure! But long experience has taught us that whilst there might be a ferry, it doesn’t always mean it’s working, and a long shot that it is taking vehicles! So, some calls are made: “Yes, the ferry is running. Yes, it can take your Defenders. Be there at 6am to ensure you get on – market days are very busy.”

The heat builds through the night alongside huge thunderheads amassing over the distant Blue Mountains of the DRC. The mozzies are thick this time of year; we toss and turn in our tents – sleep almost impossible – and are up early to head for the Waseku ferry point.

At dawn, Lake Albert (called Lake Mabuto Sese Seko on the DRC side) is like a mirror; there’s not a breath of wind, and we’re sweating buckets by the time the ferry arrives. Hundreds of passengers carrying bales of second-hand clothes jostle for space as the two expedition Defenders squeeze on board between taxi-bikes and trucks crammed with giant bunches of bananas, dried fish and who-knows-what.

As the ferry casts off, we look over the passenger balcony: scores of ladies have already made themselves comfortable on colourful pieces of cloth underneath the vehicles and are fast asleep!

A drunk man leans over Kingsley’s shoulder as we page through Andrew Robert’s excellent ‘Ugandan Great Rift Valley’ book to reacquaint ourselves with stories connected to this historic part of Africa’s geography. He comically repeats everything in a loud, beery voice – we become the ferry’s floating audiobook! The book also mentions the huge storms that brew up without warning over Lake Albert, ‘taking boats and men to their deaths in numbers’.

Nearing the Panyimur port, we look up to find 15 pairs of eyes avidly awaiting the next instalment. But behind them, there’s a massive thundercloud with curtains of rain bearing down on the ferry. A howling wind comes from nowhere, the lake turns into a seething froth, and the sky goes black. There are a few tense minutes as the ferry battles to the dock, and we slowly inch the Defenders through the crowd of passengers running for cover onto terra firma. Just another of Lake Albert’s legendary storms; 30 minutes later, everything is calm again – it could have been very different.

We later reach the frontier Ugandan town of Arua. To our shock, it’s transformed from a small, non-descript border post into a major transport route. We can’t believe the scene: scores of fuel tankers and 18-wheelers carrying colossal mining equipment and containers clog the road – street vendors are doing a roaring trade. As we wait our turn, four young dudes in baggy hip-hop jeans expertly roller-skate past, dodging water-filled potholes and weaving through the melee to the sounds of pounding rap music. Only in Africa!

In this colourful chaos, we meet the short, rotund, and very jovial Odra Gaston, a delightful character who assists African Parks as a trans-border facilitator; once again, we’re reminded of AP’s extensive network across Africa. Odra disappears into the customs and immigration post. A faded, limp DRC flag struggles to flutter in the still air thick as syrup with humidity as we watch a passing parade of cross-border travellers and traders on foot, by bike, boda-boda and truck.

We breathe a sigh of relief as Odra marches out of the building with our paperwork and stamped passports. The straggly muddy string stretched across the road is let down, and we’re through. “Remember, drive on the right!” shouts Odra as we take a wet, red mud road into the DRC and reach the small town of Arua, where at an old Belgian colonial building that serves as African Parks’ logistics hub, we meet our Garamba escort team. In true Congolese style, we’re greeted with friendly smiles, shouts of “Bienvenue!” handshakes and selfies as they gather around the mud-splattered expedition map on the bonnet.

Waving farewell to Odra, our convoy sets off, the Defenders in the middle with two heavily loaded Garamba escort vehicles in front and behind. In charge are the cheerful and smartly uniformed ranger duo of Matu and Innocent – Matu with an earpiece and in constant comms with HQ.

After a long, wet eight-hour slog through mud and rain and close to the park, a brilliant double rainbow appears ahead in the dark grey skies. “That’s a good omen,” says Shee, leaning forward to rub ‘Congo’, the expedition’s little bronze rhino talisman on the dashboard we bought in the Kinshasa market years ago. “You’re back home again,” she says with a smile. Garamba National Park, here we come.

War and peace

The expedition Defenders are thick with red-brown mud as we arrive, waving torches in the dark. Out of the rain and gloom steps a tall figure wearing a wide-brimmed Aussie-style hat under which are friendly eyes, a broad smile and a firm handshake. “Welcome to Garamba – I’m Philippe Decoop, the new park manager,” he says in French-accented English. “I’ve only been here a week myself but how fortunate to have you as my first guests. And Kingsley, you’ve brought the rain – a great deal of it! The Dungu River is rising, and the bridge into the park is already underwater. But don’t worry – as you South Africans say, we’ll make a plan!”

Better than camping in the rain again, our base becomes Camp Dungu, a charming lodge with small cabins built some years ago on the banks of the now-rising Dungu but sadly, because of the conflicts in this part of the DRC, the lodge has hardly seen a visitor. On a hardwood table is a beautifully crafted book titled ‘Garamba – Conservation in Peace and War’, which immediately becomes our reference for this part of the expedition. On the opening page is a paragraph from Peter Fearnhead, AP’s CEO:

“Garamba National Park is at the nexus of Africa’s conservation challenges. Poverty, war and civil unrest within and across the eastern DRC’s borders have bred a proliferation of armed insurgents who see rich pickings in the park’s wildlife resources, creating a level of security threat to the park’s wildlife and human inhabitants that is almost without equal in Africa. Operating in Garamba requires extreme dedication, resilience and endurance, and we’re proud of the teams on the ground, past and present, who have dedicated their lives to preserving Garamba.”

African Parks joined forces with the DRC’s Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation (ICCN) in 2005 to manage and restore this 5,900km² park after years of decline, but it hasn’t been easy. In 2008, a brutal armed conflict erupted. Garamba became the epicentre of a battle against the notorious Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), one of the most vicious rebel forces in Africa, who moved across the Ugandan border and into Garamba, setting up permanent bases and entering the illegal ivory trade in a big way to fund their guerilla war – a single tusk buys a lot of firepower.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari lodges and campsites where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? You can plan and book your African Parks safari by clicking here.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari lodges and campsites where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? You can plan and book your African Parks safari by clicking here.

The LRA launched a series of attacks on Garamba’s rangers and surrounding villages – attacking the Park’s Nagera HQ, killing 15 rangers and wounding 13 others – massacring thousands of community members and abducting hundreds of children; using the girls as sex slaves, turning the boys into child soldiers.

This galvanised the Ugandan army to join forces with the US in ‘Operation Lightning Thunder’—the aim: to root the LRA out of Garamba and capture Joseph Kony. US-backed air strikes destroyed LRA camps inside the Park, but the mission was a failure; most LRA fighters and Kony vanished into the vast rainforests that straddle the DRC/CAR border. The LRA took revenge in another series of brutal attacks, with civilians, rangers and wildlife paying a heavy price. In one day alone, 50 elephants were killed in a hail of lead.

Other militia groups and poaching syndicates took advantage of the years of mayhem, and by 2014, only 1,000 elephants remained in Garamba – down from 22,000 in the 1970s. The northern white rhino – for which the park had been made a World Heritage Site – was wiped out. Garamba was in the headlines for all the wrong reasons, recognised worldwide at the time as ‘Ground Zero’ in Africa’s poaching wars. Then, a public campaign against Joseph Kony and the LRA captured global attention, with millions worldwide staging mass protests, highlighting the plight of Garamba’s last elephants.

The good news is that Garamba is steadily clawing its way back thanks to international support and the tenacious, tireless work of its rangers. It now employs 500 permanent staff and serves as an anchor of stability for the entire region. Wildlife numbers are slowly increasing, too, and last year, only one elephant was lost to poaching. Our humble expedition is another story of hope and heroic human resilience for Africa’s iconic wilderness areas.

The following morning, up at dawn, we head deep into the surrounding forests, travelling north. It’s the sort of adventure that 4×4 enthusiasts would love. Through the lost-in-time town of Nagero with its colonial-style buildings dating back to the Belgian days, then slipping and sliding along narrow bush tracks with dense palm groves and thick elephant grass taller than the Defenders, through swamps and black-cotton-soil mudholes scattering wallowing pigs, ducks and chickens, crossing rivers on rickety plank bridges, passing shaggy-thatched, low-roofed mud huts with small patches of maize, cassava, bananas and millet, and colourful wash-day laundry spread out to dry in the sweltering humidity, which soon has us adding Rehydrate to our water bottles.

Hours later, we’re waved down by a small crowd who’ve cleared a track through the bush. Following them, we dodge tyre-puncturing stumps to be welcomed by excited, flag-waving farmers loudly singing and dancing to the rhythmic sounds of a Congolese ‘adumgu’ (traditional handmade guitar). This agri-project is one of the best we’ve seen; water from a nearby swamp is being channelled into a large, hand-dug tilapia fishpond, below which is a vegetable garden full of cabbages, tomatoes, eggplants and onions. Garamba’s agri-trainer, Carl Moumbogou, explains that the project has over 260 farmer-leaders, each working with ten other trainee farmers. “That’s 2,600 new farmers now providing fish protein and vegetables to Garamba’s neighbouring communities,” he says proudly.

Still, further north, the heat burns down, and the humidity is as thick as cassava porridge. In a forest clearing, we meet up as planned with the park’s mobile clinic run by medical orderly Timothy Lupay and nurse Ruth Tcheka, who are clearly popular with the mums and babies who’ve gathered for check-ups and the malaria prevention nets we’ve brought. It’s a hugely colourful event; the ladies singing and laughing and so appreciative, and the elderly giving toothy grins as they patiently wait for eye tests and reading glasses. All the mud and sweat are truly worthwhile – adding soul to this Afrika Odyssey journey to connect all 22 African Parks-managed conservation areas across Africa.

It’s nearly dark when we return to the Park’s HQ, hot, dehydrated and crusted in mud. Garamba’s community manager, Josiane, is relieved to see us and confesses she’s never done that road in the rainy season. After the intense heat of the day, a colossal storm brews again and lets forth a deluge that continues all night.

The next morning, Ross isn’t looking good and goes down like a tonne of bricks. He immediately begins malaria treatment, but it gets worse. The park’s Dr Diyo does blood tests: it seems Ross has a double-whammy – malaria and typhoid. Massive doses of antibiotics are added to his treatment. “You guys carry on,” Ross says stoically, pouring sweat and shaking as tummy gripes and fever take hold. Thank goodness this has happened here where there’s medical support, and we’re not somewhere deep in the bush.

With assurances that the camp staff and Dr Diyo will keep checking on the patient, Philippe, armed with the expedition calabash, has us racing for the helicopter. “We must move quickly – more rain’s coming,” says Oggie, the funny, charismatic pilot sporting a badge on his flight suit that reads: ‘Stop screaming, I’m scared too.’

To the clatter of rotor blades, we sweep over waterlogged plains, spotting a herd of elephants, wallowing buffalo, hippo and a pride of lions. We land on the summit of Bagunda Hill, Garamba’s highest point, which serves as an observation post with forever views across a mosaic of beautiful open savannah grasslands, rocky outcrops and riverine gallery forests that stretch to the South Sudan border. The rangers help us select pebbles for the symbolic stone cairn (Isivivane) we’ll build at the end of this fascinating journey.

Back in the chopper, Oggie’s excited voice comes over the headphones. “Look – there they are – the rhinos! Let’s land.”

Four months before we reached Garamba, 16 southern white rhinos were flown from Zululand in South Africa to this remote northeastern corner of the DRC – a considerable task undertaken by teams of conservationists in both SA and the DRC. It’s an emotional experience for Shee, who’s given years of her life to rhino conservation. On spying on them, she lets forth a loud ‘HALALA!’ Zulu-style ululation that startles the rangers. For her and us all, it’s a special moment to see rhinos back in Garamba, monitored 24/7 by a specialised ranger team; it’s clear what a massive commitment this has – and will – entail.

And so, the decision is made – the symbolic calabash filling will happen at the rhinos’ drinking spot. We follow their muddy tracks to reach a swampy pool dominated by a large sausage tree laden with heavy fruit hanging on long stalks. As the new park manager, Philippe is given the honour and receives directions in French and English: ‘Go over there – non-non, pas ici – go further – ARRET!’

At the top of a small bank, Philippe launches himself onto what looks like a firm bank of sand on the pool’s edge – and with a sludgy-sounding plop! sinks deep into soft mud, desperately hanging onto the calabash as his Aussie-style hat falls over his eyes. His efforts to extricate himself are too funny for words. An armed ranger comes to the rescue and also sinks into the mire as he digs like a honey badger to extricate Philippe’s large boots. By this time, everyone is reduced to hysterical fits of mirth!

Philippe takes it all in his stride and heroically captures a trickle of rhino water in the expedition calabash from under the sausage tree – narrowly missing getting decked by one of the large fruits. It’s a hilarious initiation for Garamba’s new park manager.

Then Oggie shouts: “Sorry folks – have to cut this short. Another storm is blowing in.” As rain spatters against the chopper’s windshield, we lift off and head back to base, only to find that the Dungu River is overflowing its banks; it could mean trouble and Ross, poor bloke, is no better.

Flooding in Garamba

Sometime later, we have good news. Ross survived his double-whammy and is back on his feet but down two belt notches and a few kgs lighter. Bad news: the Dungu River is in full flood – it’s getting serious.

Still, there’s work to be done. We splash along waterlogged roads to the park’s environmental centre for a vibrant Umuganda Day. Phillipe and most of the HQ team are there and, despite worries about the rising waters, determined to embrace African Parks’ 10th value: have fun. Garamba regularly hosts children to teach them about wildlife and their environment, including kids from refugee camps close to the South Sudan border. It is great fun – full of happy smiles and laughter.

Then, a special surprise: a sprightly 92-year-old arrives on the back of a boda-boda (motorbike taxi). It’s Mibolinabiko “Mzee” Bazigbiu, proudly wearing his old Garamba park uniform. He’s the last surviving elephant handler from a time when the Congo domesticated elephants to work in agriculture.

Strange to hear in these modern times, but domesticating African elephants goes back more than 2,000 years. From the ancient Kingdom of Kush at Meroë in what is now the Republic of Sudan, stone-carved hieroglyphics detail how African elephants were caught and transported up the Nile in specially-built barges, then across the Mediterranean Sea to Rome. They participated in ceremonies, parades and war; known as ‘breakers of walls’, African elephants were the tanks of many Roman conquests. They were used to terrify the enemy’s horses and flatten fortifications – their prowess is celebrated in mosaics and paintings that still survive today. In 218BC, the famous Carthage general Hannibal set out from modern-day Spain to attack Rome, and his army included some 40 trained-for-war African elephants. In the old city of Axum in northern Ethiopia, some texts that pre-date Christianity depict African elephants harnessed in teams to raise the giant granite stellae. But for the next 1,800 years, there’s no mention of domesticating African elephants and the methods used died out with the demise of these ancient civilisations.

Now, with Matu translating into English, we learn from the ‘Elephant Man’ that in 1899, King Leopold II of Belgium (he of Heart of Darkness infamy) issued a royal decree: ‘Catch some African elephants and domesticate them’. By the 1940s, 80 elephants were being used for agricultural and forestry work, cared for by a team of ‘cornacs’ (mahouts); one of them was Mzee Bazigbiu’s father.

“I, too, became a cornac and in the 1960s, we celebrated our independence from Belgium but within months, the army rebelled and our country went up in flames,” he tells us. “Those were terrible years, and the Simbas, a fierce rebel group, came to Garamba to kill for ivory. So, I and the other cornacs swam with our elephants across the Dungu River and hid for eight months in forests and swamps where the poachers’ trucks couldn’t go.”

“Things got better and the elephants were busy with conservation work in Garamba and other jobs. They starred in films! But many of them aged and poaching became a big problem again. Then in 1984, Madame Kes (Hillman-Smith) arrived with her husband Fraser and with a few rangers, worked so hard to rebuild Garamba. But then, people didn’t like to mix with elephants anymore. Kiko, the last one, died of old age. And that was the end. I loved our elephants, and I miss my brave friends.” The old man heaves a great sigh and wipes his eyes.

Today, Garamba is home to both savannah and forest elephants, the endangered Kordofan giraffe, buffalo, and hippo, 14 antelope species, lion, leopard, spotted hyena, golden cat, and 13 primate species—to name a few.

It’s humbling to hear Mzee Bazigbiu’s story in his own words – it brings the past to life. With a new pair of +2,5 reading glasses, he animatedly gets involved in the kids’ Wildlife Art competition. What’s incredibly heartwarming is the respect he receives from both children and the Garamba team, as more pages in the expedition’s Scroll for Conservation are filled with powerful stories of life amid conservation and war, written in Congolese and French.

But by evening, streams of water are snaking through the tall elephant grass and trees – the roads now submerged. The expedition’s heavily loaded Defenders make heavy progress back to Camp Dungu, at times breaching the one-metre wading depth even on high-lift. We’re told this is the highest floodwater in 20 years, and evacuation plans are made. As a precaution, we reverse the Defenders onto a giant anthill, store passports, vehicle papers and important kit in waterproof bags and join the Garamba team for a Congolese-style braai. Then the heavens open yet again – all part of this great adventure!

We’re woken by shouts at dawn – Camp Dungu has become an island in a sea of water, and the roads have completely disappeared. But there’s an important event we can’t miss. Help arrives in the form of the park’s huge, old, 6-wheel-drive military truck. We’re hauled on board, joining Philippe and other staff members whose houses have flooded during the night. We pass the Defenders – still OK but not for long – and churn through the coffee-coloured water to the Park’s HQ for Garamba’s ‘reveille’, a 100-year-old tradition. It’s a special weekly ceremony that everyone attends: the DRC and Garamba flags are solemnly raised, rangers parade and salute smartly, the park manager gives words of encouragement and tribute, and the national anthem is sung loudly.

Then it’s action stations – all hands on deck, the evacuation plan goes into overdrive – orders are barked, and staff scatter in all directions. A boat is dispatched to rescue equipment and belongings from Camp Dungu and the flooded houses. A warning goes out – crocodiles have been sighted cruising between the buildings. Still, with a vast amount of good humour, the now homeless staff are squeezed into every space available. But there’s still the problem of the expedition Defenders stuck on their lonely anthill.

We’re now apprehensive – how the heck will we get them out? Kingsley whispers that he’s mentally crafting a message to Land Rover along the lines of: ‘We regret to inform you that the new Defender 130s, the best expedition and humanitarian vehicles we’ve ever driven, have vanished in record floods in the remote north-eastern corner of the DRC….’

An urgent escape route is needed; otherwise, we’ll be in big trouble. Ross goes into a huddle with Philippe and some of the ranger corps. “What are the chances of cutting a path to higher ground? It’s our only option.” A gang of workers quickly get to work, attacking the thick, thorny scrub with razor-sharp machetes. In no time, they hack out a narrow 2km track. But it’s not over yet; fording a fast-flowing stream to reach the escape route, Ross’ Defender bogs down and has to be winched to safety. Jagged, tyre-puncturing tree stumps and big rocks lie hidden in long grass; it’s a tense, low-ratio crawl as rangers walk ahead, shouting warnings and heaving obstacles out of the way. The heat and humidity is unrelenting.

Spattered with sticky black muck, we finally reach the Park’s HQ and start setting up a temporary camp – only to hear more ominous news from Matu. “We must leave now. A bridge on the road to the border is about to go under. If we delay, you could be stuck here for days.”

It’s a mad dash to say farewell to Philippe and the Garamba team, who have become firm friends in a few action-packed days – we’re deeply sorry to leave. With Matu and Innocent again leading the convoy, we tackle the long, churned-up road back to the Ugandan border, crossing the drowning bridge and passing scores of folk pushing their motorbikes and bicycles through thick mud. In low-lying areas, the road disappears into great pools of water; we see a flotilla of quacking ducks paddling past a group of men trying to shove a swamped car onto drier ground. It’s slow going, and by early evening, we’ll still be hours away from the border. Help comes from an unexpected source: the Kibali gold mine, which helped finance the recent return of rhinos to Garamba, welcomes us with warm hospitality for the night – never has a cold Tusker beer, chicken and chips tasted so good!

At the border, it’s a jolly reunion with Odra, the fixer who helps us easily cross back into Uganda. We point the Defenders north; our next objective is to reach the next parks on our parks 14 and 15 of this Afrika Odyssey journey – Badingilo and Boma National Parks in South Sudan – which mark the turnaround point for this chapter.

PS: We later heard from the Garamba team that after we left, the floodwaters kept rising for over a week—we got out just in time!

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()