CAT, MONGOOSE OR SOMETHING ELSE?

![]()

The island of Madagascar has been isolated for the last 88 or so million years, giving the fauna and flora of the island ample time to evolve into an eclectic assortment of strange shapes and sizes, from cat-sized chameleons to hairy, long-fingered aye-ayes. For evolutionary biologists, it is a wonderment of ecological mysteries that have the potential to provide an unparalleled insight into the way life as we know it has developed. There is one peculiar creature that presents the archetypal Madagascan enigma: an animal that looks like a bizarre cross between a mongoose and a cat, and, quite possibly, a civet. Despite being the island’s largest predator and having a fundamental role in the Madagascan ecosystem, the fossa (also spelt fosa) has always lurked in the shadows cast by the more popular and better-researched lemurs.

1. What is it – a cat? A mongoose?

The simple answer is that the fossa belongs to its own family: the Eupleridae, but the riddle of their classification has kept biologists occupied for centuries. Edward Turner Bennet first described the fossa in 1833, identifying it as a kind of civet and, therefore, part of the viverrid family. To complicate matters, however, the fossa has several features in common with the felid (cat), herpestid (mongoose) and viverrid (civets and genets) families, including retractable claws, felid-like dentition, a viverrid-shaped skull and a herpestid body structure. As technology developed, biologists increased the tools in their species-classification process, but even then, no clear answer presented itself. A series of studies conducted in the 1990s still resulted in different conclusions – one DNA study grouped the fossa with the herpestids. In contrast, another morphological study concluded that they should be grouped with the felids.

Finally, in 2003, scientists conducted extensive nuclear and mitochondrial gene analysis to prove conclusively that all carnivores in Madagascar share a common ancestor that excludes all other known carnivores, though their closest relatives are Asian and African herpestids. Thus, the fossa and the 9 other endemic Malagasy carnivores were placed in their own family: the Eupleridae.

The relationships of the individual species within the Eupleridae are still poorly understood but, as it stands, the fossa’s closest relatives are the two falanouc species, the Malagasy civet, the ring-tailed vontsira and four Malagasy mongoose species.

2. Madagascar’s dominant (natural) predator

While the astounding predatory skills of members of the mongoose and civet families are often eclipsed by the dramatic larger carnivores, their hunting style is acrobatic and lightning-fast. The fossa’s hunting prowess is equally formidable – combining cat-like power with mongoose speed and agility. Equally at home on the ground or in trees, fossa are capable of adjusting their feet to either a plantigrade-like (walking on the souls of the feet like a human)or digitigrade-like (walking on its toes, and not touching the ground with its heels, like a dog) gait, and the ankle joints in their back legs are extremely flexible, allowing them to descend trees head-first.

An adult fossa can reach lengths of around 1.5m (including its long tail) and can weigh over 8kg. They are opportunistic hunters and will feed on rodents, birds, and reptiles, as well as invertebrates. Their main prey, however, is lemurs, some of which can reach almost the same weight as the fossa themselves. Interestingly, while fossa are primarily solitary in nature, Mia-Lana Lührs (one of the world’s few experts on the fossa) witnessed three males cooperatively hunting a sifaka. She believes that this may well be an evolutionary throwback to a time when giant lemurs existed on Madagascar.

3. Battle of the sexes

Even though males are slightly bigger than females, the mating process is dominated by the female by the simple expedient of conducting her dalliances in a tree. In a highly seasonal behaviour most similar to lekking (seen in some bird and antelope species), a female in oestrus ascends a tree judged to be sufficiently sturdy to accommodate energetic activity (often reusing the same tree year after year) and calls loudly to declare her status to the males in the area. For up to a week, would-be suitors gather at the mating site, competing for her attentions, and suitable males will be permitted to join her on the branch for a few hours at a time. The process is accompanied by cacophonous vocalizations and astounding displays of dexterity.

Mating is somewhat protracted due to the backwards facing barbs on the male’s penis (which itself can extend to between his front legs), and the formation of a copulatory tie. Penile spines are relatively common in the mammal kingdom and usually consist of small barbs of keratin which are believed to play a role in triggering ovulation or removing copulatory plugs. They are found in many members of the cat, rodent and primate families, though it appears, mercifully, that human ancestors lost theirs around 700,000 years ago.

4. Going through changes

Litters of up to six youngsters are born in a suitable den after a 90-day gestation period and stay with their mothers for the first year, only reaching sexual maturity at around 3-4 years of age. This relatively slow developmental process also translates into an extended life expectancy – fossa in captivity have been known to live over 20 years. Bizarrely, young females display what is known as transient masculinization: at around 1-2 years, the clitoris enlarges and develops spines similar to a male’s penis. This gradually diminishes in size as the female reaches sexual maturity, and it is possible that this mechanism reduces harassment by adult males and/or aggression from adult females. This transient masculinization is extremely rare in the mammal kingdom.

5. There may be fewer than 2,500 fossa left in the world.

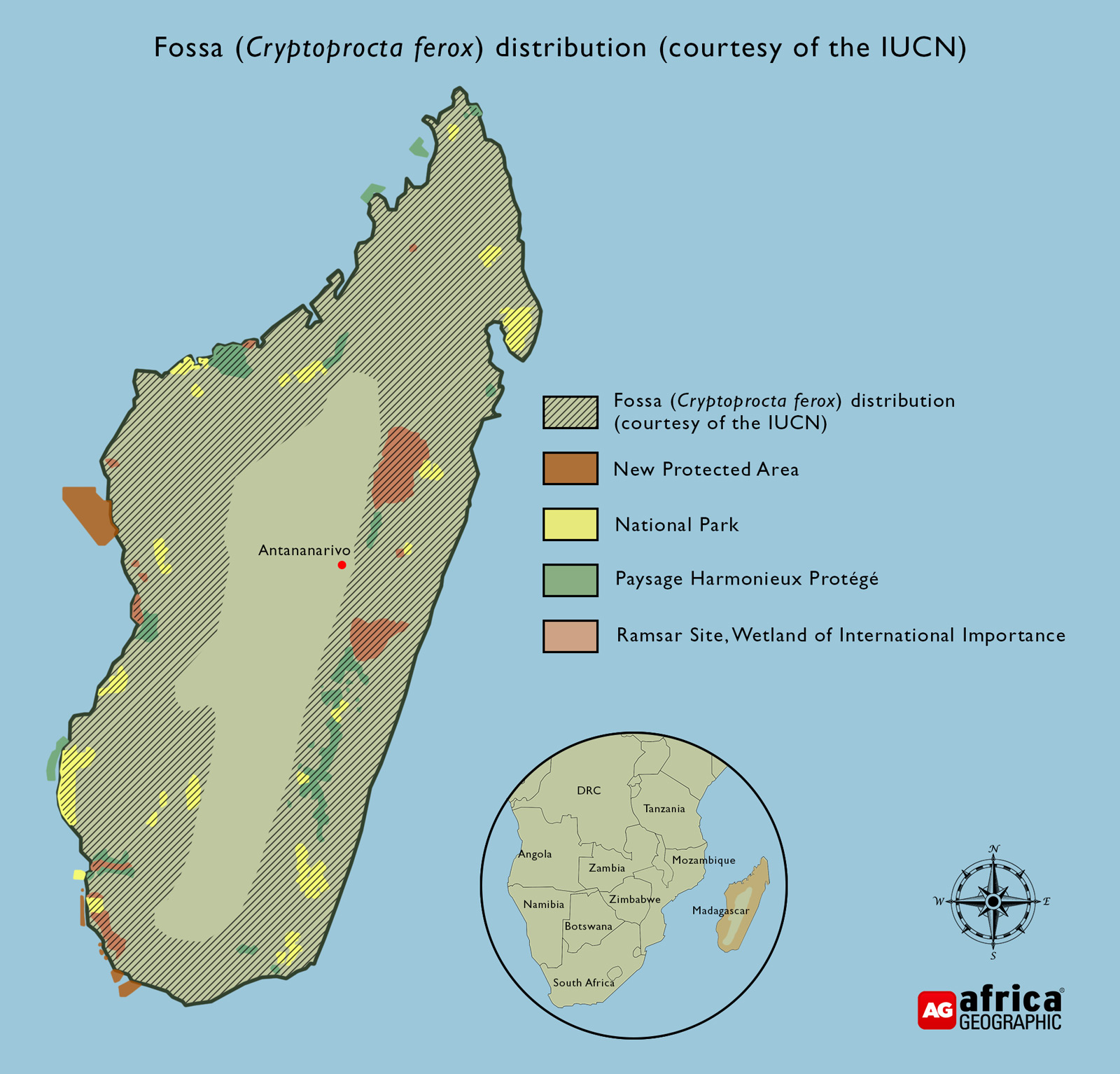

And this may be an overestimate. The fossa population size is challenging to measure, but research suggests that only the Masoala-Makira and Zahamena-Mantadia-Vohidrazana forest ecosystems are of sufficient size to support a population of more than 500 adults. Despite their widespread distribution, fossa seem to occur at extremely low densities for a predator of their size, which in turn makes the fragmented and small protected areas available to them insufficient to support viable populations. While they are currently listed as ‘vulnerable’ by the IUCN Red List, the reality is that the fossa may be far more threatened than most realize.

Like all of Madagascar’s fascinating fauna, fossa are faced with the combined threats of habitat loss and fragmentation. Slash-and-burn agriculture is common, and forests are continually destroyed to increase grazing land for local cattle. When natural prey is scarce, fossa turn to surrounding villages in search of food, putting them in conflict with people and domestic animals and, while in certain parts of Madagascar it is considered taboo to consume the fossa, they are still regularly hunted for bushmeat.

Conclusion

The lemurs of Madagascar might steal most of the limelight, but the island’s largest carnivore should not be forgotten, underappreciated, or relegated to the status of the ‘antagonist’ of the forests. The evolutionary conundrum that is the fossa is one of nature’s works of art – powerful, agile, intelligent, and enthralling in its own right.![]()

WATCH: Baby fossas run off with camera!

WATCH: Baby fossas run off with camera!

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()