We asked Botswana-based wildlife veterinarian Erik Verrynne to shed light on the issue of whether fences prevent elephant migrations and restrict their movements in northern Botswana. This clarification is required after this research paper ‘The 2020 elephant die-off in Botswana’ by van Aarde et al, on 11 January 2021 [1] and our summary . In it, the authors claim that fences are an underlying cause for the elephant mortalities in NG11/12 (Botswana) in 2020.

Wildlife vet Erik Verrynne:

Introduction

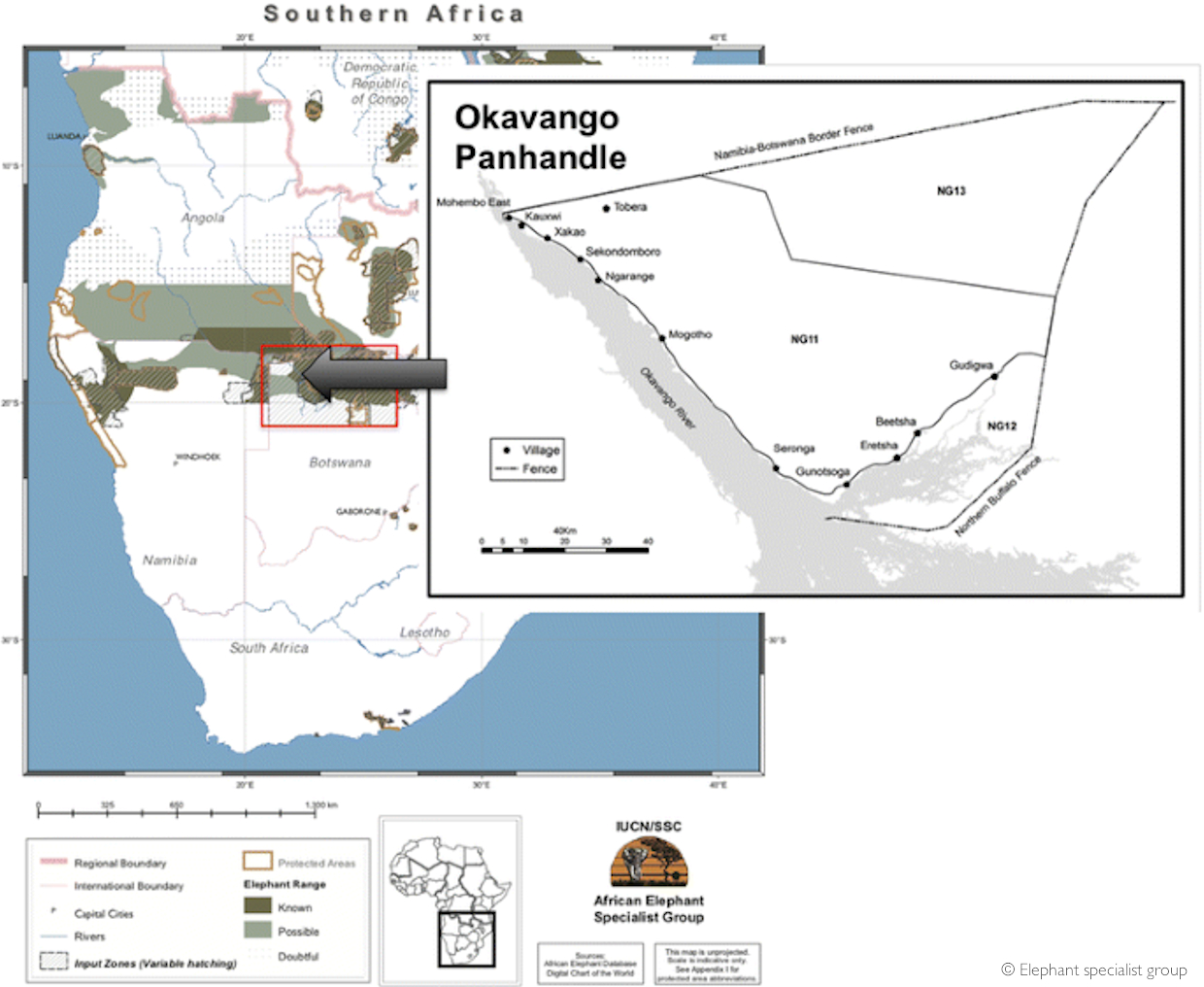

The scientists used movement data from 13 collared elephants in the Seronga area between 2003 and 2006 to prove that the elephant population is unable to cross barriers formed by surrounding fences, deep-water channels of the Okavango River and human activity (harassment).

- The study concluded that the ‘boxed-in’ effect created by the boundaries prevent elephants from migrating to other areas during times of food pressure, or from regularly reaching the fresh water of the Okavango River.

- The elephants are therefore forced to drink the stagnant water of the waterholes which increases stress and the risk of drinking pathogens such as cyanobacteria toxins or infectious agents.

- The underlying stress in a growing, boxed-in elephant population is a potential cause of increased disease susceptibility and contributed to the die-offs.

- They postulate that the ‘boxed- in’ effect would have enhanced the fast spread of the agent within the population but prevented the spread to other populations outside the Seronga area.

The article places the die-offs and the underlying ecological drivers within the context of the resistance hypothesis and the metapopulation theory by proposing the realignment of veterinary fences to promote dispersal.

Botswana relies on the dispersal of elephants into the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA) to reduce its large elephant population. At the same time, it is trying to prevent cattle contact with potentially disease-spreading cloven-hoofed wildlife species in order to protect beef export markets. More than 20% of the elephant population in Botswana shares land with subsistence beef and crop farmers where fences are used to protect cattle against disease. The Seronga area, with 15 000 elephants, is an area where both elephant crop damage and disease restrictions have socio-economic implications for the communities.

The potential of commodity-based trade is currently being investigated in Seronga as an alternative to veterinary fencing. Additionally, the Government of Botswana (GoB) has been looking into designs of species-specific targeting fences, while NGOs are working hard on programmes such as Ecoexist to promote coexistence between communities and elephants.

Despite all efforts, the dispersal of elephants away from Botswana as a long-term solution remains a challenge. Figures released by GoB indicate that only about 20% of the large KAZA elephant population is dispersing freely between countries, mainly between Botswana and Zimbabwe. The challenges are further illustrated by dispersals deeper into Botswana during the drought of 2017/2018 rather than into neighbouring range states.

What is causing the resistance to dispersal and do fences and channels play a role?

The reasons for the low dispersal levels in many areas seem to vary. Proposed solutions follow a large-scale approach based on general assumptions, often ignoring local factors.

The article suggesting that fences facilitate elephant deaths illustrates the challenges we face. Remote sensing data is used to postulate drivers and causes, and to offer solutions, while local knowledge or fieldwork critical to verify the collected data is ignored.

The fences around the area are the double veterinary border fence between Bwabwata NP in Namibia and the Seronga area of NG11/NG13 in Botswana, and the northern buffalo fence. The latter fence was erected in 1995/96 to prevent the spread of contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (CBPP) that came across from Namibia. CBPP was declared under control in 1998 only after the mass slaughter of 320,000 cattle.

Albertson (1998) reported how the northern buffalo fence cut off migratory patterns of zebra and elephant, causing the death of migratory species and even an elephant cow and calf. The original fences consisted of sturdy 1,2 m – 1.4m high wooden posts and intermediate wooden droppers connected with strands of steel wire and a single strong steel cable to strengthen it against elephant damage. At the time the fences were regularly maintained to prevent the crossing of any cattle or buffalo. After CBPP containment and the subsequent removal of the Setata fence in 2003, seasonal migrations of wildlife across the removed fence resumed. Therefore, in some cases, fences can present effective barriers to elephants.

The authors of the article stated that the fences in question are still being maintained and therefore present impermeable barriers to elephants wanting to disperse. A quick visit would have immediately shown that this is not the case. Even the current condition of the international boundary fence is not capable of blocking the movement of cattle or buffalo in certain places although in general, it appears much sturdier than the northern buffalo fence.

Over the last few years, I have visited different parts of the fences in question with the exception of the western section of the international boundary near Mohembo, and the section of the northern buffalo fence from the Selinda gate to the north through NG13.

The sections of all the fences I visited had gaps where the fence was either on its side, or most steel wire strands and wooden intermediate droppers were missing. In many cases, the connecting steel cable was on the ground, covered by vegetation. Elephants and antelope were crossing the northern buffalo fence at will while I saw tracks of a few solitary elephants crossing the double vet boundary with Bwabwata NP.

The presence of active photographic tourism lodges and sporadic patrols by the Botswana Defence Force may account for the fact that there is reportedly little poaching in NG12. Neither the fences nor the small amount of human activity on the southern boundary are likely to restrict the movement of elephants out of the Seronga area.

Realignment of the current veterinary fences, even removal of the international boundary fence would not, in my opinion, have a significant impact on, or resolve future cases of disease outbreaks in elephants in the area as claimed by the authors.

Elephant reluctance to move across the deep channel at Seronga remains a mystery. Elephants along the Chobe River cross deep water at will. We regularly see bulls and family herds crossing over onto the sinuous islands, wading chest-deep across the deep channels around Kadizora and Xanaxara. The reluctance to cross water may simply be driven by individual behavioural preferences.

If it is not the fences, why are the elephants not moving?

Verifying the movement data to see if the elephants are indeed not moving out of the Seronga area should be the first reaction. Unfortunately, it is difficult to see if the presented data support the statement of a ‘boxed in’- effect.

The authors present data of only 13 elephants within the Seronga and adjacent areas between 2003 and 2010 while reference to 25 more collared elephants was not supported with data and therefore could not be considered. Therefore, the lack of access to raw and other referred movement data, and the historical nature of the data makes it difficult to place the claims in perspective.

However, other collaring data and anecdotal evidence and observations confirm the lack of mass dispersals of elephants in and out of the Seronga area. Local seasonal movements between food and water sources inside the Seronga area by a large part of the population and very localised seasonal movement of small numbers between NG12 and NG16 are regularly-reported occurrences.

Dispersal does not happen spontaneously. It must be driven by a catalyst usually generated by a change in resources, environmental conditions, or threats strong enough to elicit a group response and overcome memories of any previous hindrance. The response must have the potential to correct or improve the situation both to the individual and the population.

Thirst is a major driver for elephant migrations or dispersals. The restricted access to water is acknowledged in the article in supporting the need to disperse. However, the authors failed to consider the opposite situation where sufficient key resources and safety may nullify the sustained pressure to disperse. In short, the elephants may not want to move because the food, water and shelter is enough for most of the year, while the conflict and harassment by people is short-lived and can be mitigated without the need to migrate.

How sustainable are the key resources?

Key resources in the Seronga area are provided by both the seasonal floodplains, long sinuous islands, and the woodlands.

NG12 is the area to the south of the line of fields and villages and is covered by the seasonal floodplains which vary in width from 3 to 10 km. Across the floodplains NG 12 transitions into a series of long sinuous islands. It ends in the sandy Kalahari apple leaf islands and shrub mopanes towards Vumbra Plains (NG22) in the south, the reedbeds of the deeper channels of NG23 to the southwest and mopane belts to the east into NG16. Many circular islands on the seasonal floodplains accommodate a variety of large riverine forest trees, with jackal berries (Diospyros mespiliformis) and water berries (Syzygium cordatum) providing much sought-after fruit in late winter and early spring. The browse potential for elephants on the circular islands is relatively low and during the dry season, some herds cross over the seasonal floodplains onto the long sinuous islands in search of food.

The most important resource on the seasonal floodplains is therefore fresh water during the dry season of May to October, and during droughts. Water in the woodlands is only available at the latest up to July. The river starts flooding the floodplains at Gunistoga in late March or early April, retracting in June but water in large pans and deep channels remains, sustaining the elephants, wildlife, and cattle until thunderstorms provide water in the north again. While the Okavango River is flowing, the channels provide water, and the floodplains remain the most important sustainability factor during drought. The woodlands to the north in NG11/ NG13 and long sinuous islands to the south provide the other key resources.

The major impact zone is the line of fields and villages along the road and banks of the floodplains where 16 000 people live in 13 villages and numerous settlements. Fields for subsistence crop farming stretch up to 15km, but on average about 6km from the villages towards the woodlands in the north.

Once past the 10 to 15km impact zone, the woodland vegetation transitions into a mosaic of deciduous broad-leaved trees in the deep Kalahari sands, alternating with more claylike soils, where a combination of shrub and cathedral mopane dominates. The woodland vegetation is lush and dense during the wet season but most of the trees lose their leaves at the height of the dry season (July, August and September). As result, a part of the elephant population crosses the floodplains to the sinuous islands where they feed on a variety of trees and mopane shrubs.

The largest part of the elephant population switches back to remain in the woodlands almost immediately when the first thunderstorms fill the pans. Only a small part of the population remains close to the impact zone, drinking from the water on the floodplains. They remain invisible most of the time, their tracks crossing the main road at night as they move between the nearby browse and the waterholes on the floodplains past the fields and villages.

Numerous waterholes or pans formed in the clay soils of the mopane woodland fill during the rainy season between November and April and provide water to the wildlife and livestock that move north into the woodlands for the wet season.

It is some of these waterholes that were implicated as sources of the cyanobacteria toxicity in the mortalities amidst much speculation. However, indications are that mortalities had already started in March when it was still raining, while some carcasses were found in flowing water on the floodplains. Both conditions are less favourable for algal blooms. In my opinion, the true cause of mortalities remains unknown and open to speculation.

Overlapping and sustained utilisation by elephants, other wildlife, people, and livestock, have created the high-impact utilisation zone with many trees destroyed and mopane reduced to shrubs. This zone represents high risk and low resource use to the elephants in the dry season because they are forced to cross the zone daily between available resources. Risk is avoided by moving mainly at night and at speed, using elephant highways and the 13 corridors demarcated by Ecoexist as known routes past the field and village lines. By this time, crop harvesting has fortunately finished. By mid-May, most fields are empty. (Crop raiding happens from January to mainly April and seems to involve a small part of the population that remains close to the impact zone.)

Why are they not dispersing during the drought and will elephants eventually move?

Elephants are hindgut fermenters that digest cellulose in their massive colons. This evolutionary adaptation does not need quality feed, but quantity – something the high-biomass mopane and apple leaf areas can provide in abundance. The adaptation also allows them to utilise twigs, branches, and bark in the absence of leaves during the dry season or drought. They can push tree resources beyond normal resilience thresholds to levels of advanced deterioration before it negatively affects the nutritional intake values, provided the elephants have access to enough water. The thermoregulatory needs of such large animals when ambient temperatures are high, also necessitate water. Elephants are able to travel more than 20 km a day between food and water, an ability that mitigates their water dependency during droughts.

Drought, impact from an increasing elephant population, and an increase in human utilisation of resources around village lines in the impact zone, are causing deterioration which is gradually widening the impact zone into the woodlands, onto the floodplains and even onto the fertile long sinuous islands. Eventually, it may reach a threshold where the abilities of the elephants to negotiate the distances to water, and the increased conflict-related harassment will be sufficient to drive dispersal or migration. Only then is it likely that they will consider moving closer to the water resources of the Linyanti, Kwando or Zambezi Rivers.

The dispersal thresholds are unknown, as the resources appear to be more resilient than the tolerance of the villagers. The ensuing conflict may burst the dam wall long before the resources give in. Managing co-existence is a challenge for Botswana

For now, the elephants seem to be staying. Not because of fences or deep-water channels, but simply because the available resources suit them. Alternative key resources may not be close enough, and they may have adapted local strategies to mitigate droughts and human conflict risks. Drivers or memories of good places far away may not be strong enough to justify dispersal despite disease or harassment. Memories of some of the old barriers is still strong enough to remove the immediate need to move to other unknown areas.

The behaviour of the Seronga area elephants raises some questions about our theories on the metapopulations and dispersal within KAZA. Maybe it is time to acknowledge that elephants exert a choice based on the available resources or even memories of what appear to be boundaries. Our expected thresholds on resource utilisation may be wrong and elephant migration preferences may be more localised. Promoting dispersal across KAZA may require stronger drivers than simply removing fences. Elephants may consider our proverbial grass as not always greener on the other side of our fences.![]()

About the author

Erik Verrynne is a veterinarian and agricultural consultant who been working in Botswana since 2003. He is a wildlife and livestock vet with an MPhil in wildlife management.

[1]van Aarde RJ, Pimm SL, Guldemond R, Huang R, Maré C. 2021. The 2020 elephant die-off in Botswana. PeerJ 9:e10686 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10686

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()