WHAT IT TAKES TO SAVE AFRICA'S MOST ENDANGERED CARNIVORE

The wolves came to Africa when the ice receded. The hypothesis goes that, as the land warmed about 100,000 years ago, relatives of the grey wolf crossed the land bridge from Europe and colonised the Afro-alpine grasslands and heathlands in the horn of Africa. The continent’s new immigrants would remain there, refining their skills at hunting rodents on the alpine plateaux, developing longer limbs, muzzles and smaller set-apart teeth until they were masters of the Afroalpine – efficient, lean, killing machines of mole rats, grass rats and hyrax.

2. The wolf pounces.

3. A female brings a freshly killed hare to a male. Being small prey specialists, Ethiopian wolves do not hunt in packs.

4. The most common victim of the Ethiopian wolf is the grass rat.

©Will Burrard-Lucas

There were never many wolves because of their limited habitat – probably a few thousand at best. Today there are little more than 500 alive, making the Ethiopian wolf the rarest canid species, three times rarer than the panda bear, and Africa’s most endangered carnivore.

‘They are victims of their success. They evolved to thrive as specialists in the Afro-alpine grassland. But because of the warming continent and the pressure of humans, now they are restricted to tiny mountain pockets, and the pressure continues ever upwards,’ explains the founder of the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme, Professor Claudio Sillero, a conservation biologist at the University of Oxford’s WildCRU.

It is not for lack of food that their numbers are small. Their Afroalpine environment has particularly high rodent biomass. ‘It holds more prey biomass than a typical East African grassland. We’re talking three thousand kilos of rats per square kilometre. It’s an amazing resource for wolves, other carnivores and many raptors,’ explains Sillero. But this environment is also a resource for cattle and goat herders, and the peril they bring is rabies by way of domestic dogs. The dogs are there to protect herds from spotted hyaenas and other predators. Ethiopian wolves do not prey on such large animals, but it doesn’t stop dogs from interacting with wolves, and inevitably they contract the virus too.

3000kg of rats per sq.km means the Afroalpine is an amazing resource for wolves

Sillero began studying Ethiopian wolves in the late eighties. Throughout that time and long before, the interaction between domestic dogs and wolves was relatively common, even resulting in hybrids. Through the neutering of hybrids and reducing the occurrence of free-ranging dogs in wolf habitats, the EWCP team is pushing hard to stop cross-breeding. ‘But in the late eighties and early nineties, we had a bunch of odd-looking wolves out there,’ Sillero jokes. He reminds me that it is through biting that rabies is transferred. The animal’s behaviour changes once the virus takes control, altering its behaviour and driving it to increase the dispersal of the virus. The animal becomes more aggressive and ranges widely, biting other creatures, including livestock and humans.

2. Domestic dogs can transmit rabies and other diseases to the wolves but are needed by the locals to protect their livestock from leopards and hyenas.

3. The alpine terrain makes things difficult for the EWCP team and, like the herders, they will often use horses to cover more difficult terrain.

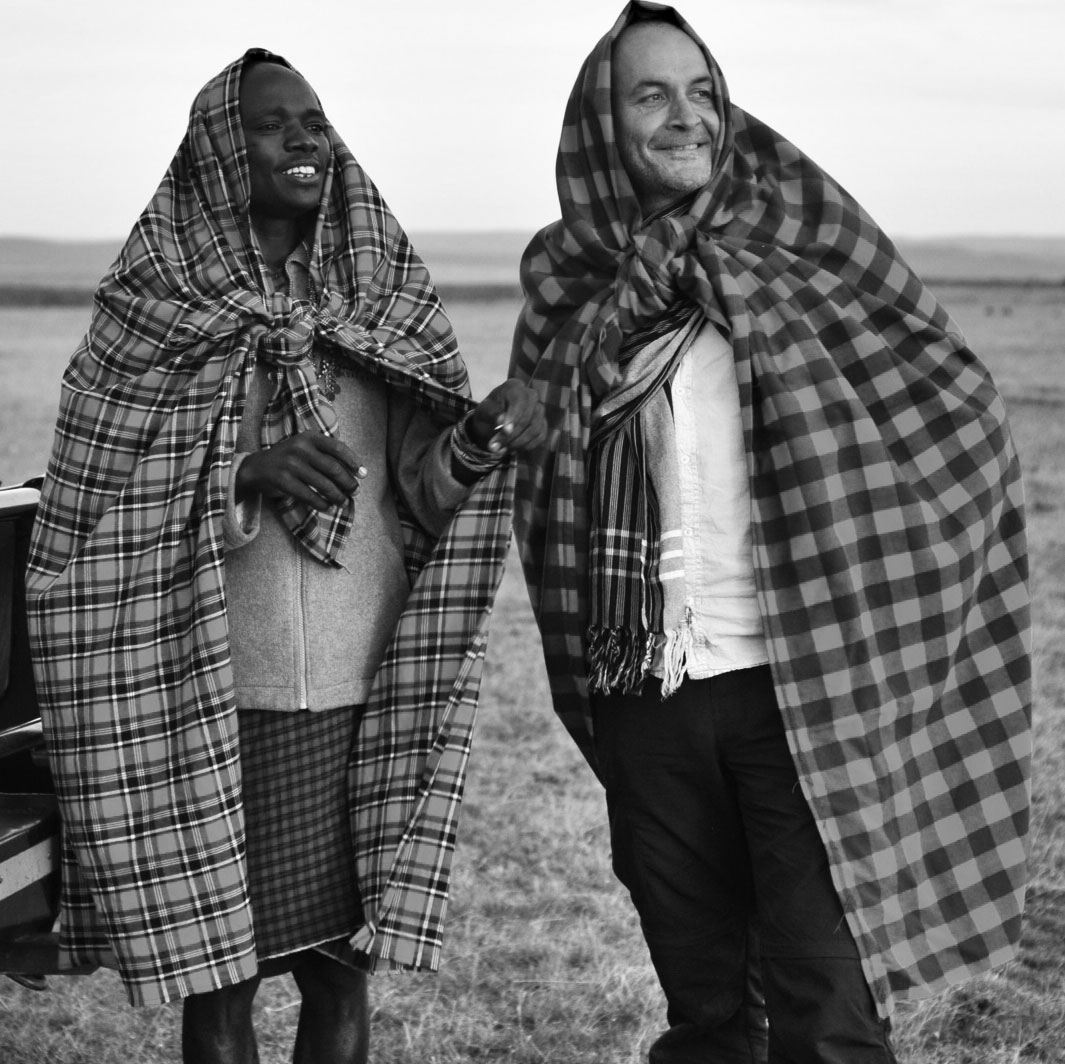

4. Professor Claudio Sillero and the EWCP team vaccinate a wolf in the Bale Mountains.

©Will Burrard-Lucas

Rabies is not unusual among Ethiopian wolves and comes around in cycles. But the latest cycle of rabies was particularly bad. ‘We have major outbreaks every ten years, but the last one was after five years, so they appear to be occurring more frequently now.’

EWCP’s team comprises 35 Ethiopian nationals and is supported by the Born Free Foundation. The Bale Mountains National Park, containing the highest population of wolves with just over three hundred individuals, is the core area of their work. On 10 July, the EWCP picked up their first carcass here. By 11 August, they had found four more carcasses testing positive for rabies and Sillero and his team began vaccinating the wolves. ‘Unless we step in and vaccinate, the impact is dire. You lose three out of four wolves in the affected population.’ In this case, a population of 66 lost an estimated 25 wolves before it appeared to be under control. Sillero remains cautious and will not declare the wolves out of danger until he and his team have monitored the situation for a few more weeks.

For the last few years, Sillero has been moving away from a reactive vaccination approach in order to implement a pro-active approach with a proven oral vaccine that is put in food. This could enable them to prevent or lessen the impact of future outbreaks and build some immunity in the population. They were testing this process when the last outbreak occurred and were able to monitor the animals that had taken the oral vaccine. They all survived. But the team’s work is never done. Specialised creatures require special management, and Sillero takes all factors into account, particularly humans.

Humans colonised the Ethiopian landscape long before the wolves

Ethiopia is also the home of Lucy, our ancestor. The discovery of this 3.2 million-year-old hominin fossil confirmed this northern stretch of the great rift as one of the cradles of humankind. Humans crossed the same land bridge as the wolves about 700,000 years earlier, in reverse. But many of us remained and shaped the land of Ethiopia over hundreds of thousands of years, particularly through farming over the last 8,000 years and domestic livestock for even longer. A lack of resources makes it incredibly difficult to prevent traditional pastoralists from entering Ethiopia’s National Parks.

Domestic dogs outnumber wolves in the National Park by more than two to one

Sillero understands the prevalence of humans, livestock and agriculture in the national parks and takes a holistic approach. ‘In the horn of Africa, the landscape is human-dominated. There is no conservation without taking the local communities into account. In the big conservation areas in Southern and East Africa, many are working with local communities because it’s the right thing to do. But in Ethiopia, you can’t afford not to.’

In the last four weeks, EWCP vaccinated 700 domestic dogs inside Bale National Park alone. They aim to vaccinate at least 70% of the dog population, but there are always new dogs coming in with the seasonal herders, and this trickle is impossible to plug with the limited capacity of Sillero’s team and the national park rangers.

EWCP educates herders about the impact of the virus on themselves and their livestock. Ethiopia has one of the world’s highest casualty rates for rabies in humans, and it also has an economic impact. ‘Some households lose about US$70 of livestock in a year. To a Bale highlands family on an income of US$200 a year, that is a significant number.’ The Oromo herders rely on horses for travel, and they also succumb to the virus adding another severe economic factor.

But the Ethiopian wolves bear the brunt of the virus. It is the one thing they are not specialised to overcome, and without Sillero and the EWCP’s work, they might very well be extinct by now.

©Will Burrard-Lucas

‘In my time, we’ve seen the wolf population in Bale oscillate between one hundred and fifty and three hundred and fifty. Social canids can reproduce well. You can have a litter of six or seven puppies annually. In a good year, you might see thirty percent growth. Then a few years down the line, you have an epidemic, and you might lose three-quarters of that population. We discourage getting too fixated on numbers.’

They try to stabilise those numbers with better enforcement of park rules, education of shepherds, vaccination of their dogs, and of course, the wolves. ‘Even if we were to reintroduce wolves to places where they are currently absent, we might be looking at six hundred, seven hundred wolves across Ethiopia, never more than that. They are inherently rare, and they are going to remain rare. Unless we succeed with our conservation efforts they will get rarer still.’ Sillero is incredibly pragmatic in his approach. He doesn’t cry wolf and remains determined, after decades of challenges, to preserve this rare species. His is a rare trait indeed.

ALSO READ: Ethiopian wolf

You can help the EWCP protect the beautiful Ethiopian Wolf by clicking here

Contributors

Wildlife photographer WILL BURRARD-LUCAS first developed a passion for wildlife living in Tanzania as a child. Since then, he has photographed wildlife all over the world and primarily in Africa. Will aims to inspire people to celebrate and conserve the natural wonders of the planet through his imagery. He has partnered with several conservation organisations donating his time and images for their fundraising activities. Working with the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme he draws attention to the challenges this species faces. You can view more of Will’s work on his website.

Wildlife photographer WILL BURRARD-LUCAS first developed a passion for wildlife living in Tanzania as a child. Since then, he has photographed wildlife all over the world and primarily in Africa. Will aims to inspire people to celebrate and conserve the natural wonders of the planet through his imagery. He has partnered with several conservation organisations donating his time and images for their fundraising activities. Working with the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme he draws attention to the challenges this species faces. You can view more of Will’s work on his website.

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, sometimes drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton has a strong empathy with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, sometimes drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton has a strong empathy with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()