THE FIRST LARGE-SCALE SURVEY OF EAST AFRICA'S CORAL REEF FISH

Coral reefs are highly complex and productive ecosystems, second only to tropical rainforests when it comes to biodiversity. They provide valuable resources for communities along the East African coast and in turn these communities have a significant impact on marine life. But these ecosystems are often data deficient because of the mammoth task involved in researching such large geographic areas. No standardised dataset had been collected on the East African coast until a small team with a small budget took it upon themselves, ultimately providing a valuable open source dataset upon which scientists, conservation and community organisations can build.

Coral reefs are highly complex and productive ecosystems, second only to tropical rainforests when it comes to biodiversity. They provide valuable resources for communities along the East African coast and in turn these communities have a significant impact on marine life. But these ecosystems are often data deficient because of the mammoth task involved in researching such large geographic areas. No standardised dataset had been collected on the East African coast until a small team with a small budget took it upon themselves, ultimately providing a valuable open source dataset upon which scientists, conservation and community organisations can build.

Their expedition included fourteen survey regions from the iSimangaliso Wetlands National Park in South Africa to Malindi in central Kenya, including some iconic diving destinations such as Sodwana Bay, Quirimbas Archipelago and Zanzibar Island. Their observations are encouraging and at the same time concerning. Personally I find it encouraging that the team decided to do this on their initiative, that they pushed on while facing enormous challenges, and that they found support when they needed it most. This is their story – Ed.

With the stadium lights of Durban fading into the night and the water lapping at the side of the boat, our small team had high hopes. Little did we know this would be our last night of restful sleep for a long while. Using a minimal budget and a team of six divers, one filmmaker, a boat and its crew, we aimed to survey the coral reefs spanning 3 500 km of coastline from northern South Africa to northern Kenya over four months. Ultimately we wanted to provide a quantitative baseline dataset for the entire East African region – to improve our knowledge of the coral reef ecosystems.

As a storm hits south of Lurio Estuary in Mozambique the team tow a fishing pirogue towards the safety of the closest shore village.

After the team were marooned in Mozambique, Ocean Adventurer 2 came to the rescue. Here OA2 chases a storm off Inhambane. ©Caine Delacy.

The weather turned from unpleasant to downright terrifying

It was quite an ambitious idea, but after much cajoling and the promise of adventure, we eventually had our team – and what we thought would be our vessel. David Livingstone once wrote, “If you have men who will only come if they know there is a good road, I don’t want them. I want men who will come if there is no road at all.” This quote became a mantra over the next few months.

Due to rough seas, seasickness took hold shortly after leaving Durban harbour. Most on board were a deep shade of green, and within a few days, the weather turned from mildly unpleasant to downright terrifying. We found ourselves at the front of a major storm off Leven Point on South Africa’s North Coast. To make matters worse, our engine broke down, and over the next 12 hours, the storm grew to a force with wind speeds exceeding 100km/h and 20ft waves that snapped our boom. Just one week into our trip, we found ourselves limping into Richards Bay with a broken boat.

There, we had to divide the team – three heading to Mozambique to begin the survey dives while the rest remained to await repairs and spare parts. The plan was to reunite in Tofo, where we would have to dive aggressively before cyclone season hit. In a week, we managed to get the boat into seaworthy shape. Spirits were high as we sailed towards Mozambique, but testing times were still ahead.

Crawling towards Tofo on the Mozambique coast late one night, there was an ominous ‘thunk’ from the bowels of the boat. Our hearts sank, and the engine stopped working once and for all. This boat wasn’t going on any expedition. We had to abandon ship, remove all our gear and head for dry land, where we installed our entire team in a small house kindly offered to us in Inhambane. Marooned there, we struggled to find justification for this faltering expedition.

We were working on scant information in areas that hadn’t been dived before

I firmly believe in Karma, and maybe we racked up a boatload of it because just when we felt we must abandon all hope, we were given a gift. The crew from OA2, who had heard about our situation, offered us their 82-foot power-driven catamaran to continue our expedition. We only had to wait a month in our little Mozambican shack in the heat of Christmas.

With the boat’s arrival after that long, drawn-out month of kicking up beach sand and agonising over our next move, we approached the project as people possessed. Our new team of 11 (boat crew and survey team combined) moved along Mozambique’s shoreline towards the spectacular Quirimbas islands, and we made up for the lost time by conducting eight dives a day for weeks on end unless bad visibility or weather forced us to take a break.

Our greatest challenge was finding all the dive locations. We were often working on scant information in areas that had not been dived before. Making decisions on which direction to head in, which side of an island to dive off or how much time to spend in a certain location became a stress-filled ritual. We quickly learned not to second-guess our decisions or spend precious time agonising over unpredictable outcomes. Every hour that went by served to remind us how far we still had to go and how little time we had.

Everyone dug deep into their physical, mental and financial reserve. To say this wasn’t a pleasure cruise would be an understatement. But we slowly ticked off the dive sites, edging our way through the 2,500km of Mozambique’s coastline and into Tanzanian waters, up through Zanzibar and Pemba islands and past Pangani. Each time we crossed out another site, our hopes rose. You could still feel the tension when we hit minor setbacks like sickness, fatigue and losing team members to their real jobs, but the atmosphere lifted as the days went by. After deciding to forgo Lamu due to potential piracy issues, we crossed into Kenya and lumbered into Malindi, our last stop. Turning around to recover all our missed dive sites, there was a definite feeling that somehow, we might be able to complete this expedition.

Before embarking, a mentor told us to write down everything we thought could possibly happen to us on this expedition. Ultimately most of the worst-case scenarios, like the storm, the breakdowns and having to abandon ship, came to fruition, and we could finally talk about them with gay abandon. I think the universe has a way of dropping you down a peg, forcing you to face greater challenges, and overcoming them. Maybe that is what adventure is all about: Not letting your fears and failures alter your chosen course.

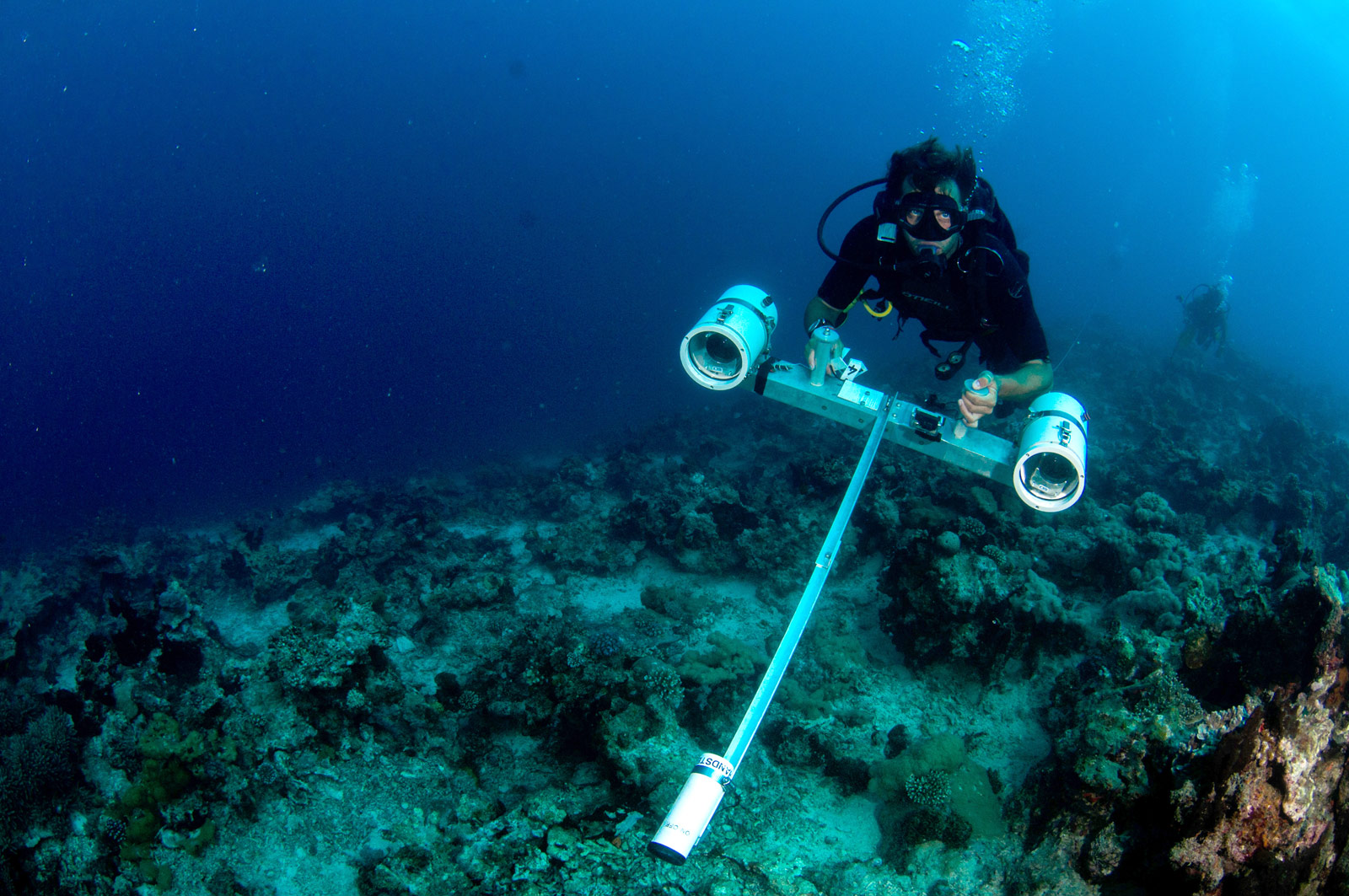

Team Scientists Dr Rhett Bennett and Mike Markovina prepare stereo video cameras for a new dive, often one of eight completed each day. ©Linda Marikovna.

A green turtle hatchling before being released into the ocean. Its nest had to be relocated to a safe section of Tanzanian beach to avoid poachers. ©Linda Markovina

In February 2013, weather-beaten, smelly and a little skinnier, we returned to Cape Town harbour’s safety. We managed a total of 224 survey dives and 26 recreational and filming dives in rapid succession. We were beat, but we were successful, and that would not have happened without the help of so many different people who fed, housed, motivated and encouraged us. We come across the same kinds of people with every expedition we take, and we tell ourselves that if we ever come across people in similar situations, we will take them in. You have no idea the difference it makes.

So, after all that drama, what did we end up discovering?

Certain no-take zones were effective in protecting important species

While no two dives were the same, a common thread emerged as we analysed the data for over a year. Encouragingly, we observed some reefs in near pristine condition, with high fish diversity and well-developed coral communities with endless large, old coral heads, which were a privilege to dive on. Numerous reefs also exhibited little evidence of fishing, with large predatory fishes and herbivorous fishes in high abundance. Potato groupers, large snapper species and a wide range of size classes and trophic levels showed us that certain well-established no-take zones in Mozambique, Tanzania and Kenya were effective in protecting important species – an analysis that favours well-managed marine no-take zones as useful fisheries management tool for the future.

But we also spotted signs of overexploited reefs in areas closer to coastal access points and around well-established local fisheries. Less large predatory fishes and a creeping dominance of algal cover signified that even herbivorous fishes had been overexploited.

A sting ray is cut up for market in Vilanculo, Mozambique. ©Anton Crone

A stereo video system developed by SeaGIS in Australia recorded all fish in a given area. This method of counting and analysing fish biodiversity reduces many biases associated with more traditionally used visual census techniques and is cost-effective and easily replicated. ©Caine Delacy

When one of these bombs explodes underwater it sends a jarring pain through your bones

With the larger predatory fishes disappearing, local fishermen resort to more effective but devastating methods as they redirect their efforts towards smaller species and species in lower trophic levels, such as spearfishing to access large parrot fishes and small-mesh gillnets to target shoals of fish too small to take baited hooks. On more than one occasion, we dived up against massive monofilament gill nets, un-fondly referred to as ‘hanging walls of death.’

In addition, the destructive effects of dynamite fishing have devastated the corals in many areas, an illegal practice entered into more boldly than one might expect. Being underwater when one of these homemade bombs goes off sends a jarring pain through your bones. This happened to us regularly while we dived on the Tanzanian coast. The destruction is total and devastating, leaving behind eerie uninhabited craters of coral rubble.

What is most disturbing, however, is that many of these observations of coral damage and nets were recorded within some marine reserves or no-take zones. We can only surmise that there is either a lack of knowledge and/or respect for protected area boundaries or ineffective management.

To avoid making sweeping statements about the status of reef fishes or the health of the corals, the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of no-take zones or the noticeable changes in reef status from one country to the next, we will leave these simply as observations for now, until it is possible to back these observations up with scientific fact.

Information sharing and scientific study, in combination, can be incredibly powerful in creating awareness, and that was the core belief that drove us to complete our expedition. The scientific community is now picking up the data and hopefully can be used to help improve resource management in the regions and facilitate the planning of future management initiatives and surveys. In fact, a second survey is potentially in the works – we are suckers for punishment and adventure, it seems. What was it that Livingstone said again?

The survey data is free to download for all to use:

Click here for access

Dedicated to Aaron, who tragically lost his life in a diving accident just after we completed our expedition. A dear soul who loved the ocean as much as we do and whose family took in a bunch of stragglers and gave them a Christmas when they needed it most. Thank you.

Contributors

LINDA MARKOVINA is a freelance travel and photojournalist. She blogs on behalf of Moving Sushi for various online platforms and writes travel guides specifically focusing on African destinations. Her main loves are writing about travel, the natural world, and how we interact with it.

LINDA MARKOVINA is a freelance travel and photojournalist. She blogs on behalf of Moving Sushi for various online platforms and writes travel guides specifically focusing on African destinations. Her main loves are writing about travel, the natural world, and how we interact with it.

Dr RHETT BENNET is a passionate fisheries scientist interested in the African oceans. Growing up along the Eastern Cape coast, he spent most of his life in the blue, studying, observing, and marvelling at everything beneath the waves.

Also read: Killifish – suspended animation

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()