The continuing saga of the painted wolves of Mana Pools

It is a year since the BBC first screened Dynasties: Painted Wolves and nearly three since they stopped filming in Mana Pools National Park in Zimbabwe. Since then, the dynasty has struggled. In part two of this trilogy (read part one here), Nicholas Dyer, who has followed these packs for the last seven years, continues the story with Blacktip’s tale.

? Like her mother before her, Blacktip well deserves the title ‘Legend’ © Nicholas Dyer

The BBC, in their Dynasties film, painted Blacktip with something of the night about her. An aggressive creature that drove her mother, Tait, into the “Pridelands” and to her death. In doing so, she put her pack in great danger, driving them to the point of mutiny. The drama concludes with the dramatic death of a female called Tennessee to the jaws of a senseless crocodile.

After the attack, they ran “all through the day… all through the night,” as narrated by Sir David Attenborough, with a heavy dose of dramatic hyperbole. Given the speed and stamina of these animals, they would have reached Botswana. The reality was that they moved five kilometres upstream and found a tiny waterhole near a place called Mucheni.

? Tennessee (right) sadly met her end in the jaws of a crocodile © Nicholas Dyer

Joy on the floodplain

What fascinated me was that they ‘camped’ here for nine consecutive days, heading off to hunt in radials at dawn and dusk. It was November and by now painted wolves (also referred to as African wild dogs) should be highly nomadic, rarely returning to the same spot on consecutive days. It appeared that Tennessee’s death shook them and Blacktip wanted a place for her subdued pack to recover from their loss near a safe supply of water.

? Left: After the crocodile attack, Blacktip found a tiny waterhole where her pack could safely drink; Top right: The magic of the pack returned after a few days; Bottom right: The waterhole also provided great entertainment value. All photos © Nicholas Dyer

Gradually the pack regained its confidence. It was punishingly hot as the Zambezi Valley waited patiently for the rains. In the late afternoons, as the brutal sun declined towards the Zambian escarpment, the pack would be released from the protective shade of the Natal mahoganies, descending a small slope to drink and play. As their self-assurance grew, so did their boisterous afternoon games as they splashed and danced in that tiny pool, while Blacktip looked on protectively. It was for me the most wondrous time I have ever spent photographing painted wolves – thirteen wolves with nine puppies doing what they loved best.

The real Blacktip

The depiction of Blacktip as a ruthless malevolent creature is not how I saw her, although her dusky features certainly lent themselves to this sinister characterisation. Like her mother before her, Blacktip was an incredible leader, commanding her pack with determination, discipline and even innovation.

I first saw Blacktip in 2014 when she led a pack of 30 painted wolves, 15 of which were her puppies. A pack that size requires cohesion and a strong leader. Rudyard Kipling summed it up perfectly:

“For the strength of the pack is the wolf,

And the strength of the wolf is the pack.”

? Taku, initially the chief babysitter, is now the alpha female of the Ruckomechi Pack © Nicholas Dyer

Blacktip and her Nyakasanga Pack were the epitome of this. As I got to know the pack over the years, I recognised that each of its members had their specialities. Her alpha male, Jiani, and three other males were spectacular hunters – swift and agile. Taku, who the BBC named Pip (after the sound her radio collar made), was a doting aunt to the pups, always attentive and willing to play. And there was Tris, a gorgeous yearling that legendary guide, Henry Bandure nicknamed “Doc” because she would always lick the wounds of the injured.

Blacktip never seemed to be an overprotective or nurturing mother. She often sat well away from the den mouth and left the babysitting to Taku. She would frequently head off with the others on a hunt, heavy milk-laden breasts swaying as she tackled fleeing impala. She loved to be in the mix on the hunt but understood the art of delegation – an essential skill in running any pack – and the un-mollycoddled pups learnt to grow up healthy.

? Left: Blacktip quickly grabs a bite to eat from Jiani, away from their gannet-like pups; Right: The pups were never mollycoddled at Blacktip’s den with yearlings pulling sleepy pups out of the cosiness of the den. Both photos © Nicholas Dyer

Blacktip, the innovator

Blacktip pioneered something that has never been recorded before – predation on baboons. The development of this critical new food source for the painted wolves of Mana Pools seemed to coincide with a boom in the baboon population.

? Blacktip pioneered the hunting of baboons, something that had never been seen before anywhere in Africa. Both photos © Nicholas Dyer

This innovation not only fed the pack, but also helped to restore some balance to the Mana Pools ecosystem. Her pack benefited by consuming less energy on the hunt and avoided many potential injuries incurred on a long chase across rough ground. Through this behaviour, Blacktip gave me two incredible gifts: a stunning photograph which got me into the final of the highly acclaimed NHM Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition, and my first article in National Geographic, both achievements of which I am very proud. For this, I will always be grateful to Blacktip.

? Forever thankful to Blacktip for “Ahead of the Game”, highly honoured in The Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition © Nicholas Dyer

A credit to her species

Like her mother, her contribution to the dwindling painted wolf population was also exceptional. Painted wolf pups have a 50% attrition rate in their first year, but Blacktip’s record far exceeded this. In 2014 all 15 pups survived until the rains arrived, in 2015 all six survived, and in 2016 nine out of the eleven made it. The following year was less successful with only four of 14 puppies surviving, but last year she had seven, and they are all still alive today.

? Blacktip would often leave the den to hunt, leaving babysitters to look after her pups © Nicholas Dyer

Many of her pups have dispersed from the Nyakasanga to take their genes across the Zambezi Valley and beyond. Creatures like Tris simply disappeared, but that does not necessarily mean she met a nasty end. She could well be the mother of a successful pack as far away as Mozambique, beyond where Painted Dog Conservation (PDC) monitors resident populations.

Taku, one of Blacktip’s daughters that I knew well, dispersed with her sister Taj and met two males near the Ruckomechi River to form her own pack. Taj passed away last year, as did one of the males, but Taku is still there today with her alpha Tafara and two little pups, forming the nascent Rukomechi Pack. Last seen, she was pregnant again.

? Like her mother Tait, Blacktip added considerably to the endangered painted wolves. In 2014 alone she had 15 pups © Nicholas Dyer

The last sighting

Last November (2018) I drove into Mana Pools just before the rains, hoping to find Blacktip and the Nyakasanga. The book launch had kept me in Europe, so I had not been in the park since August. They had been sighted near the Ruckomechi River, so PDC’s exceptional tracker Thomas Mutonhori and I headed out to find them. On the way, the heavens opened for the first time that season. It was torrential, and very quickly Mana Pools turned into a lake.

Alone in our convoy of two cars, we stopped regularly to tow, dig and winch each other out of glue-like mud. Thomas picked up signal some two kilometres away – coming from a newly collared female called Tray, but neither my Landcruiser nor his Land Rover could make it any further. We decided to continue on foot, Thomas with his tracking gear and I with my kikoi-wrapped camera. We jumped over small streams and walked around massive newly formed lakes. While we would have been happy to wade, it is amazing how quickly crocodiles take up residence.

After a three-hour zigzagging walk, we found them – Blacktip and the other adults huddled under a tree against the rain. Like us, they were drenched, and the puppies seemed in awe. It suddenly occurred to me that they had never seen rain before. They stared perplexed into newly formed puddles and seemed strangely subdued by this new sensation of water falling from the sky.

? The pups look amazed at the water falling from the sky and waterholes forming before their eyes © Nicholas Dyer

I was ecstatic to be with Blacktip and Jiani again, and took a few photos but spent more time watching them. I had missed them greatly, and this was the first time I had seen her pups since the den. Eventually, she rose, summoned her pack and led them deep into the sodden bush.

As they disappeared through the dying drizzles of the storm, I wondered whether I would ever see her again. Although looking fit, she was now aged nine and bordering on the maximum life expectancy of a painted wolf. I shuddered, but not because I was cold and wet. I felt the hollow sadness of a passing era but was also grateful that I had got to see her at least one last time. Tears rolled down my face, thankfully disguised by the rain, although I could sense that Thomas felt the same. We started our long walk back in silence. This was the last anyone saw of her.

? The last photograph ever taken of Blacktip (top left) fading into the rain © Nicholas Dyer

The Three Degrees

When Thomas returned to the park the following April (2019), he messaged me to say he had found the Nyakasanga pack – minus Blacktip. The familiar few days of hope lingered until a few sightings later when Thomas confirmed that Blacktip did not make it through the rains. Her final fate is unknown, but old age was good enough for me.

I went into Mana a short while later and met up with Thomas to find the pack. We headed back along the road we took in November, laughing at the visible dried-out ruts and the memories of what caused them when we were last there. Thomas eventually picked up Tray’s signal deep in the mopane forests on the western boundaries of the park. We followed on foot – they were still on the move although it was a bit too late in the morning for hunting.

Eventually, we saw them under a tree. But there were only three painted wolves. It was Tray and two of her sisters, Poet and Lylie. Where were the others? There was no sign or tracks to suggest the rest of the pack was nearby.

? Blacktip’s dispersed daughters, ”The Three Degrees” – Lylie (left), Tray (centre) and Poet (right) © Nicholas Dyer

We soon figured that these girls were dispersing from the main pack and out to form a pack of their own. I met up with award-winning writer Sue Watt in a nearby lodge. For the next three days, we followed them as they meandered around the park, while Thomas focused on finding the rest of the Nyakasanga.

I named the girls “The Three Degrees”. Tray and Poet were both three years old, while their younger sister, Lylie, was just two. Poet seemed to be the potential alpha, although all were incredible hunters. They were often taking two impalas between the three of them every day, getting their fill and leaving the rest for the hyenas. They were also covering considerable ground, marking their territory continuously, advertising for some wandering males.

Sue wrote a staggeringly beautiful twelve-page article in September’s issue of Wanderlust magazine, which is a joy to read. She became emotionally attached to The Three Degrees, and she expresses this so well through her writing.

? Left: Lylie is a beautiful painted wolf and incredible hunter; Top right: Poet stood out as the most likely candidate to be alpha female among “The Three Degrees”; Bottom right: Beautiful Poet. All photos © Nicholas Dyer

The rest struggle on

Meanwhile, Thomas had found the remaining members of the Nyakasanga Pack, and I joined him a few days later. Jiani, now the 10-year-old widower, was still alive but looking very frail. All his older offspring had disappeared. Now the eldest were the inexperienced two-year-olds Whiskey, Gamma and Vincent. The other seven remaining wolves were yearlings, Blacktip’s pups from last year. They were all siblings, and Jiani was the father of them all.

The outlook for this pack was now very uncertain. There was a significant lack of experience and frail leadership. The pack continued to look after the old man, but it was hard to escape the conclusion that he was holding them back and possibly even putting them in danger. Despite these challenges, they remained full of energy and joy and looked healthy and fit.

While out of the park, I received another message from Thomas to say that he had watched Jiani continually humping Whiskey. My humanness made me feel a little queasy at the thought of this randy old man and his daughter, but that soon passed when, shortly after, Thomas called me to say that a lion had killed Jiani. The old man had finally passed, and with Tammy struggling on the other side of the park, the dynasty was in peril.

? Jiani was now very old and limping © Nicholas Dyer

Who’s the Daddy

A month later, Whiskey was looking unequivocally expectant, despite it being well outside the regular denning season. Her late father was the only suspect. She denned where she was born, a favourite spot for both her mother, Blacktip, and grandmother, Tait. She had five healthy puppies who are bizarrely both the second and third generation of Tait’s dynasty. As far as I know, this incest is unrecorded. Painted wolves’ dispersal patterns are generally designed to ensure a high genetic diversity. There is still no male that has taken up the alpha role, although as usual, all the members of the pack are enthusiastically helping to raise the pups.

? The second and third generation of Tait’s dynasty © Nicholas Dyer

They moved onto the floodplain; ten adults and five puppies, all well and strong. In mid-October this year (2019) I returned to Mana Pools in the hopes of seeing them again. Henry Bandure and Simeon Josia (who both guided the BBC) and I eventually located the pack sleeping on the western edge of the park. We watched the tightly knit bundles of fur for half an hour, but try as we may we could unfortunately only see two pups shielded in the centre.

Eventually, the pack awoke and performed a half-hearted greeting ceremony, and the two pups started hoo-calling for their lost siblings. No reply came, though the pups continued their haunting cry until the pack disappeared into the dusk.

? Left: Whiskey’s little pup looks around for her three lost siblings; Top right: The two surviving pups head off looking very sad and forlorn; Bottom right: The other ‘Three Degrees’: Henry Bandure, Nicholas Dyer and Simeon Josia – all of whom share a deep passion for the painted wolves. All photos © Nicholas Dyer

Their melancholic cry lingered in my soul for the rest of the night. Finding the pack the next morning confirmed the demise of other three pups, most likely to the jaws of deadly hyenas. These young painted wolves probably didn’t have the skills and experience to defend against a brutal attack. But some part of me couldn’t help feeling that while very sad, it was probably for the best. Through no fault of their own, the pups were severely inbred and carried with them potentially serious consequences for the local gene pool.

? Despite being inbred, Jiani and Whiskey’s pups look healthy and full of boisterous fun © Nicholas Dyer

A new beginning

Meanwhile, the Three Degrees moved down the Zambezi and soon found themselves in Tammy’s territory. Tammy had just left the den with her ten pups, and the three females were regular visitors. These female rivals caused Tammy visible stress at first, although her three remaining males (Jimmy, Timmy and Taurai) were far more sanguine. But perhaps recognising the weakness of her pack, she soon accepted their presence, and while keeping them as outsiders, she increasingly allowed them to come and play with her pups.

After a few weeks of these growing encounters, Tammy’s pack was attacked by hyenas in which all but one of her pups were killed. Tammy herself sustained a massive wound to her right shoulder. Two days later, Tammy succumbed to her injuries and passed away. This left the three males to look after the last remaining pup, but unfortunately, the little pup did not survive for long.

It did not take long for the Three Degrees – Poet, Tray and little Lylie – to get together with the last surviving Nyamatusi members – Jimmy, Timmy and Taurai. Even more interesting is that they have recently been joined by another of Blacktip’s daughters, Tsoko, who dispersed earlier this year and went missing. It is now a new pack in the making, and it is yet to be decided who out of the seven will become the alphas. We will not know this until the start of the breeding season next year.

But one thing we do know for sure. With concerns over the inbreeding within what was left of the Nyakasanga, these seven painted wolves provide the strongest known thread from which the incredible dynasty of Tait, Blacktip and Tammy can continue.

? Will next year see this new pack have lots of pups to continue this incredible dynasty? © Nicholas Dyer

Epilogue

Since the end of the filming of Dynasties, those packs made famous by the film and immortalised in my book Painted Wolves: A Wild Dogs Life, which I co-authored with Peter Blinston, have struggled. It is a time of flux, and while to the casual observer, the painted wolves continue to provide tremendous entertainment and superb photographic opportunities, underneath this, the dynasty is under pressure.

But given the terrain, the absence of people and the protection of PDC and ZimParks, Mana Pools should always remain a haven for the painted wolf and one of the most spectacular places to see them.

For me, following the painted wolves of the Zambezi Valley for the last seven years has been an incredible privilege, albeit an emotional journey. As anyone who has seen the Dynasties film will testify, they bring such incredible joy, but with that comes deep sadness when you see them suffer. They have become an integral part of my life, my feelings woven into a never-ending roller-coaster of delight, anguish and despair. But I would not stop that ride for the world.![]()

? Blacktip enjoying the sunset and some peace away from her pack © Nicholas Dyer

MANA POOLS NATIONAL PARK

Mana Pools National Park in Zimbabwe is a World Heritage Site and one of the last true wildernesses in the world. It is the only park in Africa where you are allowed to walk alone, albeit at your own risk. It is also one of the best places to view painted wolves. Many of the photographs in this article were taken at the den. Nick visited the dens under the guidance and supervision of Painted Dog Conservation (PDC) and ZimParks in preparation for the campaign to raise global awareness of this endangered species. Denning season is a sensitive time for the painted wolves and Nick, and PDC would strongly discourage den visits for reasons unrelated to conservation. They would, however, strongly encourage visitors to thoroughly enjoy painted wolf sightings but always treat them with respect and observe the sensible Mana Pools’ “Code of Conduct”.

ABOUT THE PAINTED WOLF FOUNDATION

The Painted Wolf Foundation (PWF)was set up by Nicholas Dyer, Peter Blinston and leading conservationist Diane Skinner. It aims to raise awareness about this much-threatened and ignored species and support organisations that conserve painted wolves on the ground. PWF is a UK-registered charity (Number 1176674).

THE BOOK

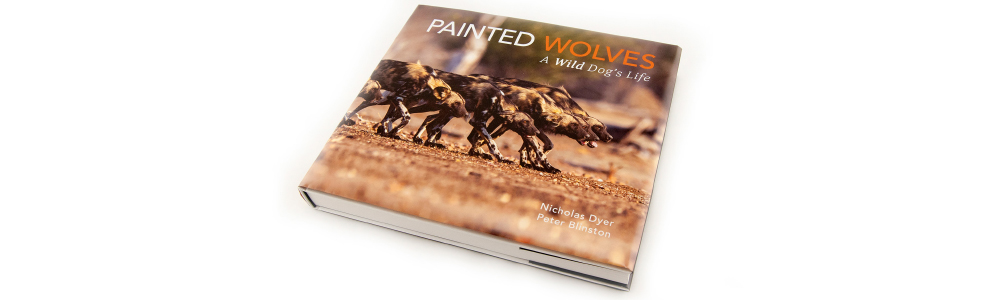

PAINTED WOLVES: A Wild Dog’s Life

The painted wolf is Africa’s most persecuted predator. It is also the most elusive and enigmatic. For six years, Nick has been tracking and photographing them on foot in the Zambezi Valley.

For twenty years, Peter has been doing all he can to save them from extinction. If there is one book that will let you into the secret world of the painted wolves, this is it, expertly narrated across 300 pages and illustrated with over 220 stunning images.

“Wildlife photographer Nick Dyer and conservationist Peter Blinston have crowdfunded a new book, Painted Wolves: A Wild Dog’s Life, which takes the reader on a fascinating journey into the lives of the painted wolves and what is being done to save them. It’s a beautiful book full of interesting facts and stunning photos, which I hope will raise the profile of the animals.” ~ Sir Richard Branson

Buy the book here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, Nicholas Dyer

Nick grew up in Kenya and after careers in finance and marketing in the UK, has found a new métier as a wildlife photographer, author and conservationist with a deep passion for painted wolves. He has spent much of the last six years photographing the packs of Mana Pools on foot while living in his tent on the banks of the Zambezi. He is a founder of the Painted Wolf Foundation and frequently gives talks around the world on this neglected species. He was an award winner in the 2018 NHM Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition and leads specialist photographic safaris in Mana and across Africa so that people can experience this stunning creature. See more of his photography at www.nicholasdyer.com, and follow him on his Facebook and Instagram page.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()