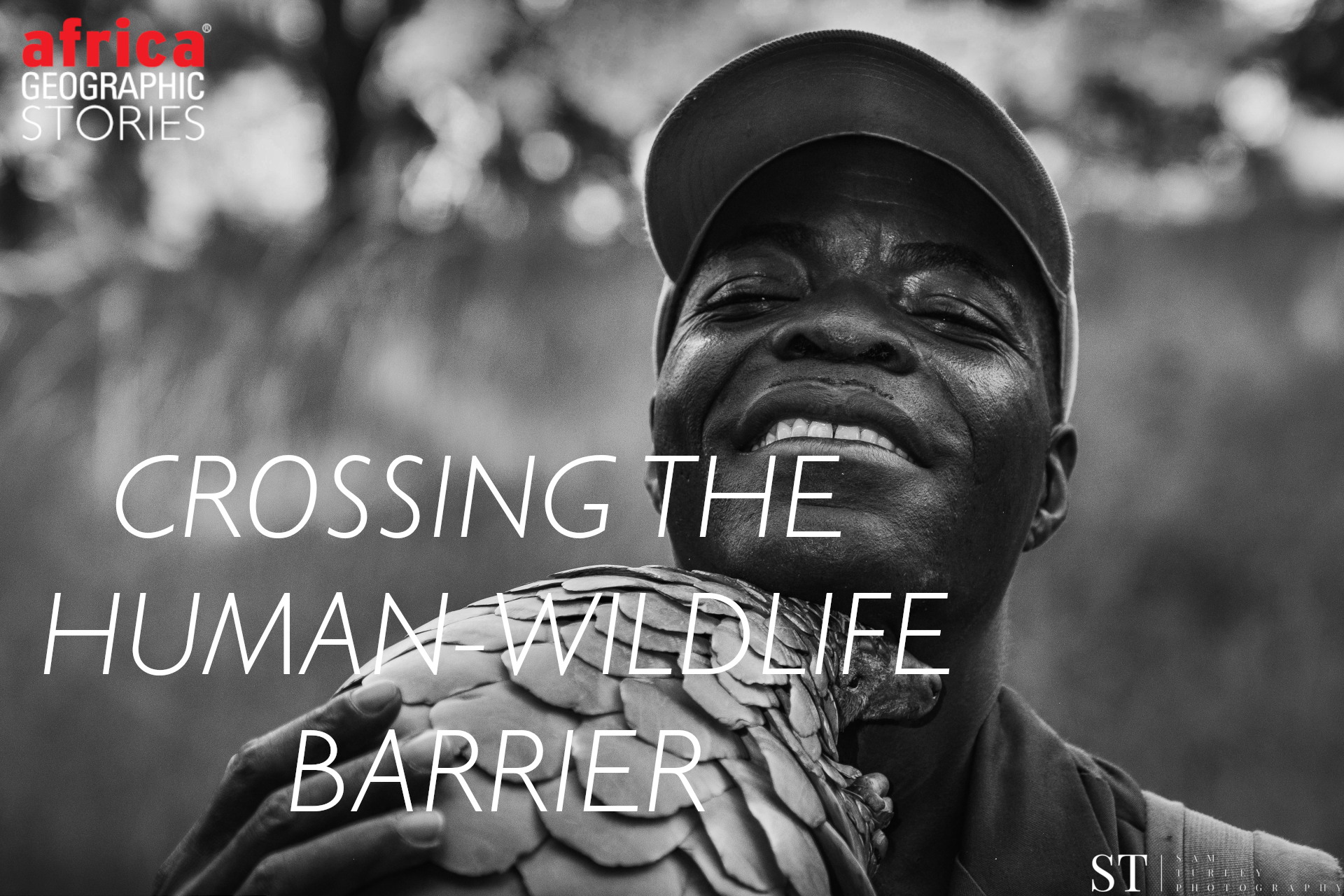

Crossing the human-wildlife barrier

Forming a relationship with a wild animal (i.e. not a dog, cat or horse etc.), or crossing the human-wildlife barrier, requires tremendous patience, motivation, knowledge and expertise – not to mention consideration of a whole host of ethical concerns.

Humans in nature

Humans have always been linked to wild animals through hunting and domestication for work, transportation, pest control, food, and, more recently, companionship. Having said this, modern humans are now so far removed from nature that many of us long to rekindle that forgotten connection – to cross the human-wildlife barrier. This desperation can often lead to confusion. What we may think is a special connection with an animal may not be – especially for the animal.

As the human population grows, wilderness areas do the opposite. Competition for space and resources is at an all-time high resulting in increased human-wildlife conflict. Although we have implemented a wide range of social, technological and behavioural approaches to reduce this problem, most of our interactions with wildlife (outside of ethical tourism) have become negative. We must find ways to coexist with wildlife, for if we don’t, it will lead to our ultimate demise.

Yet, as wildlife becomes rarer, many of us are drawn to it like a moth to a flame. However, how close is too close and when do we end up getting burnt? Wild animals are, after all, just that, wild.

Human-animal relationships

When I think about crossing the human-wildlife barrier, I struggle to think of positive examples. Poaching or “pets” that turn into problems, spring to mind. For many, nature is a place to be feared, with many species viewed as dangerous pests. So how can we shift this perception, and is it possible to form relationships with wild animals without it being detrimental to them?

During my time working with wildlife in Southern Africa, I have been fortunate enough to witness several human-wildlife relationships. Over the past year, I have made it my mission to document, analyse and, where possible, celebrate the human-wildlife connection.

Wildlife interactions can be controversial, depending on the unique circumstances of each animal and the motives of the organisation or individuals involved. There are positives and negatives to be considered when crossing the barrier between humans and wild animals and the best interests of the animal should always be of paramount importance.

In this story, I feature three unique and extraordinary human-wildlife relationships that I have been lucky enough to photograph. I discuss the often controversial ethics surrounding each.

Mateo and Marimba

Marimba, a ground pangolin, was around a year old when her mother was poached for her scales. Marimba was simply too young to fend for herself. Her rescuers took her to Wild is Life sanctuary in Harare, Zimbabwe, where she met her full-time carer Mateo.

Pangolins are notoriously difficult to look after in captivity, requiring particular and personal care. Mateo’s gentle nature seemed like a perfect fit, and a remarkable relationship was born.

Pangolins are naturally nocturnal; however, for their safety, Marimba and Mateo go out in the day so she can satisfy her insatiable appetite for ants and termites. Marimba and Mateo have spent ten hours a day together for the past 13 years, and it shows – they are inseparable. Many attempts have been made to rewild Marimba, but she always finds a way back to Mateo. She is simply too attached to him and has never learnt the essential skills required to survive in the wild – perhaps because she was orphaned so young.

As Marimba cannot be released, she will now live out the rest of her life at the sanctuary as an ambassador for her species so that others do not succumb to the same fate as her mother.

Do not be fooled by their reptilian appearance – pangolins are affectionate, gentle, sentient creatures. And they are rapidly disappearing from our planet. As the most trafficked animals in the world, most human-pangolin interactions end in another pile of lifeless scales.

In a perfect world, the close connection between Marimba and Mateo would have never existed. However, this relationship has elements of what all humans should strive to emulate in our relationship with pangolins if we are to save them from extinction—one of trust, love, and compassion.

Like me, I am sure many would rather see Marimba released into the wild than live an unnatural lifestyle with Mateo. However, even if Marimba could be released, the reality is that pangolins are being poached all over Africa at an unprecedented rate, so where could she be released safely? Her habituation to people means that releasing her at this stage could be a death sentence.

Vera and Meme

Meme is a blesbok – a beautiful, medium-sized antelope characterised by a striking white blaze. They occur at Imire Rhino and Wildlife Conservancy in Zimbabwe, although they are naturally endemic to South Africa.

I played a significant role in this particular rehabilitation. Meme was only two weeks old when she was found roaming Imire without her mother. On the third day of searching, we found a dead cow, her enlarged teets indicating that she’d recently given birth. After much deliberation, we decided to catch Meme and raise her.

Why were we interfering with nature? Why did we cross the human-wildlife barrier? It seems to go against Darwin’s survival of the fittest. There were, however, some unique circumstances surrounding Imire that we considered carefully. At the time that Meme was orphaned, there were no predators on Imire. There is no doubt that if she’d been left alone, she’d have died a long and painful death – without predators, a total waste of life. For me, hand-raising any wild animal should only be considered almost as a last resort.

Vera was tasked with the rehabilitation and ultimate release of Meme. She spent hours on end trying to convince the tiny calf to drink milk from a bottle. Sometimes force-feeding was required, but eventually, Meme took to drinking from a bottle with ease.

This example highlights some crucial points pertinent to crossing the barrier between humans and wildlife. Raising Meme was a constant internal battle between doing what was right for the animal versus doing what made us happy. I mean, let’s be honest, how amazing is it to have a blesbok following you around wherever you go? It is an entirely natural and almost unavoidable feeling to become attached to an animal you have raised.

A considerable part of that connection from the animal’s side was, of course, the food. It was tricky to judge exactly when to stop feeding her, and it became more difficult as both parties enjoyed the process. We probably fed Meme for at least a month longer than necessary. Luckily feeding her for longer than required wasn’t to her detriment, and she remained fit and healthy throughout the process.

Throughout the entire process, the goal remained to release Meme back into the wider reserve. The rehabilitation would have been pointless if we had simply kept her as our pet and denied her the right to live as a blesbok should. Meme was released at eight months old. Remarkably, she’s joined a herd on the reserve, leaving her human parents behind for a life in the wild. This was the perfect outcome for her and for our crossing of the human-wildlife barrier.

During our time with Meme, we gained a newfound appreciation for this often overlooked antelope species. Although the life of one antelope is just a drop in the ocean for conservation, it is everything for that individual. Many successful conservation projects rely on compassion, and rehabilitation stories like Meme’s can have profound and far-reaching effects. Teaching others to care about nature is half of the battle for, as Jane Goodall said, In the end, we will conserve only what we love.

Kim and the hyenas

Kim Wolhuter is a renowned wildlife filmmaker and conservationist from South Africa. What distinguishes his work from all other filmmakers is the incredible bonds that he forms with his subjects. Kim spends a minimum of eighteen months on each project and this extended period ensures that the animals he works with are completely relaxed in his presence. Through gaining unprecedented access to his subjects, Kim’s goal is to dispel myths that cloud certain species and ultimately restore our connection to nature.

There are very few mammals with a worse reputation than the spotted hyena. Kim has made it his mission to change that. Disney started villainising hyenas with The Lion King – smelly, dirty, ugly, devious scavengers.

Kim is based in the Sango Wildlife Conservancy in Zimbabwe, where he has formed a remarkable, tactile relationship with completely wild hyenas.

He works with three basic but critical rules:

- He never carries a weapon – being armed can lead to arrogance which some animals might detect (although not as arrogance obviously but possibly as overbearing dominance).

- The hyenas come to Kim apparently purely for affection. He NEVER feeds them. When food is involved, Kim will often remove himself from the situation.

- They make the rules. Every interaction happens on their terms. Kim positions himself near the hyenas and waits for them to come to him.

Many people regard Kim’s work as unethical, interfering with wildlife and changing their natural behaviour. There is an element of truth behind changing their behaviour because, of course, if Kim wasn’t there, the hyenas wouldn’t walk up to him. However, this can also be said for safari vehicles. Just because an animal has become used to vehicles does not mean they enjoy the interaction. I have seen countless examples of safari vehicles having adverse effects on animals, yet far fewer people think of these as unethical.

Is Kim’s interaction with the hyenas harming them? From my experience, not. As pictured here, the hyenas appear to love the affection, and after all, the interactions are strictly on their terms. If they didn’t want it, they wouldn’t approach him.

The other often raised concern is that the animals habituated to Kim will be more vulnerable to poaching. There is no doubt that animals pick up on our body language, and a poacher will move very differently from somebody with innocent motives. The hyenas also know Kim individually; just because he has got the clan used to him does not mean that they will be comfortable in the presence of others. I experienced this firsthand.

To get these immersive, eye-level images, I also had to be low to the ground in and amongst the hyenas. Many of the cubs approached me in a familiar setting for the clan out of curiosity but with extreme caution. None of the adults came to within five meters of me, whereas they were more than happy to receive scratches from Kim.

I think most of the opposition to Kim arises because he is doing what no others are. It is in our nature to fear the unknown and to question different practices. A lot of people discount his work as unethical without ever researching what he does. Kim has dedicated his life to protecting wildlife, and by showcasing the relationships that he forms with his subjects, he allows others to feel what he does. A love of wildlife. The value of that alone to wildlife conservation is impossible to quantify.

Potential pitfalls

Apart from the concern that habituation makes wild animals more vulnerable to poaching, there are a number of other pitfalls associated with crossing the wildlife-human barrier.

Habituation can be potentially catastrophic for both people and the animals involved – animals that lose their fear of human beings could become a risk to people and property. It is important to remember that all wild animals pose a risk, no matter how “fluffy” or “cuddly” they appear to be. In my opinion, that risk increases tenfold with the introduction of food. Animals close the gap in order to enjoy whatever morsels we have to offer. I have witnessed it many times whilst working with wild animals, things can change quickly. When we introduce food, we are often too close to the animal to react in time and this is when accidents happen. More often than not, strong food-related habituation ends in disaster. It is hugely important that a holistic view of the risks associated with habitation be taken before any attempt to cross the human-wildlife barrier is made. Could the animal become a danger to human beings? Could it become a danger to property?

There are, however, different levels of habituation and I assume that with our ever-growing human population and the resultant pressure on habitats, most animals on our planet are now habituated to some degree. Whether they have become used to game drive vehicles, people, or our infrastructure, habituation is now unavoidable. For the safari industry, some level of habituation is necessary for good sightings of animals. You wouldn’t want to pay $20,000 on your dream safari just to see the backsides of animals running away from your vehicle but equally, you wouldn’t want to spend that amount of money to be charged by an expectant elephant whose lunch is late.

It’s a fine balance, but there certainly are different levels of habituation and not all are bad. Having said this, wildlife should never become reliant on humans for food. Food-related habituation should only be explored in rehabilitation or wildlife management scenarios, and even then, it should be undertaken with the highest level of care.

There is also the fear that people might try and mimic situations they do not understand, resulting in injury or death and the subsequent euthanasia of the animal involved. Caution should therefore be taken with any publicity associated with human-wildlife interactions. Warnings and ‘do not try this at home’ admonitions should always accompany careful explanations of situations where the human-wildlife barrier is crossed.

Conclusion

Each scenario is unique. Before working in conservation, I was sceptical of almost all interactions that crossed the human-wildlife barrier, and I would dismiss them as unethical. In today’s social media culture, I think it’s essential to do your research before judging organisations and individuals that get close to wildlife. Still, I think it’s equally important to ask those difficult questions. Why is the animal there in the first place? Is the interaction necessary? Does it negatively affect the animal? What are the long-term goals, and can the animal eventually be released? If not, why not?

Crossing the human-wildlife barrier is not something that should be taken lightly. Wildlife is, after all, wild, and although I have highlighted what I believe are three success stories, it does not always go that way. I have heard of a wildebeest disembowelling a horse, a warthog killing a child and a cheetah mauling someone. No matter how cute or cuddly wild animals may be, they are all potentially dangerous.

Having said this, when done correctly, there are substantial potential benefits to crossing the human-wildlife barrier. As modern-day humans, no matter how far we remove ourselves from nature, we will always be a part of it. Wherever you live in the world, every action affects the natural systems of our Earth. With our ever-expanding population, we have no choice but to interact with wildlife. With the current state of our planet, we also have no choice but to interact positively.

About the author:

Sam Turley was born in Staffordshire, England, in 1992. Growing up in the countryside, Sam’s fascination with the natural world started at a very young age and has never left him. He has since dedicated his life to wildlife conservation, and after studying zoology in the UK, he went on to qualify as a field guide in South Africa, where he worked for three years. During a trip to Namibia in 2016, Sam’s passion for wildlife photography ignited, and he has been obsessed ever since. He was the overall winner of the 2020 Wilderness Safaris People’s Choice Award and was a three-time finalist in the highly prestigious 2020 Natural History Museum’s Photographer of the Year competition. His work has also been featured in many magazines, including The Telegraph, Getaway and Travel Africa. Sam is moving back to the UK in October to start a family. He is available for photographic and videographic conservation-related projects. You can contact Sam on sturleyphotography@gmail.com

Instagram: samturleyphoto

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()