Land of legends & giant red tuskers

Each of Africa’s national parks and protected areas has its own rich, vibrant history, and some, like Tsavo, have had a more challenging road than others. Shaped by the country’s history, a fair share of luck, and often the blood, sweat, and hard work of passionate conservationists, Africa’s protected wild spaces are treasure chests of our natural resources.

Often, due to their complex histories, some of these wild spaces engender a kind of mystique, especially true for Tsavo East and West National Parks. As part of the broader Amboseli-Tsavo ecosystem, Tsavo is captivating – a feeling of vast space and the ancient magic of the truly wild. Thick red soils stain the leathery skins of its sizeable elephant population, and the sight of a herd of red elephants crossing the Tsavo River beneath lush palm fronds is one not easily forgotten. The sometimes-harsh beauty of the landscape captured the heart of Denys Finch Hatton (‘Out of Africa’ – Karen Blixen’s lover) in a way no other wild space (or woman) ever had, and it was there that he was killed when the plane he was piloting crashed.

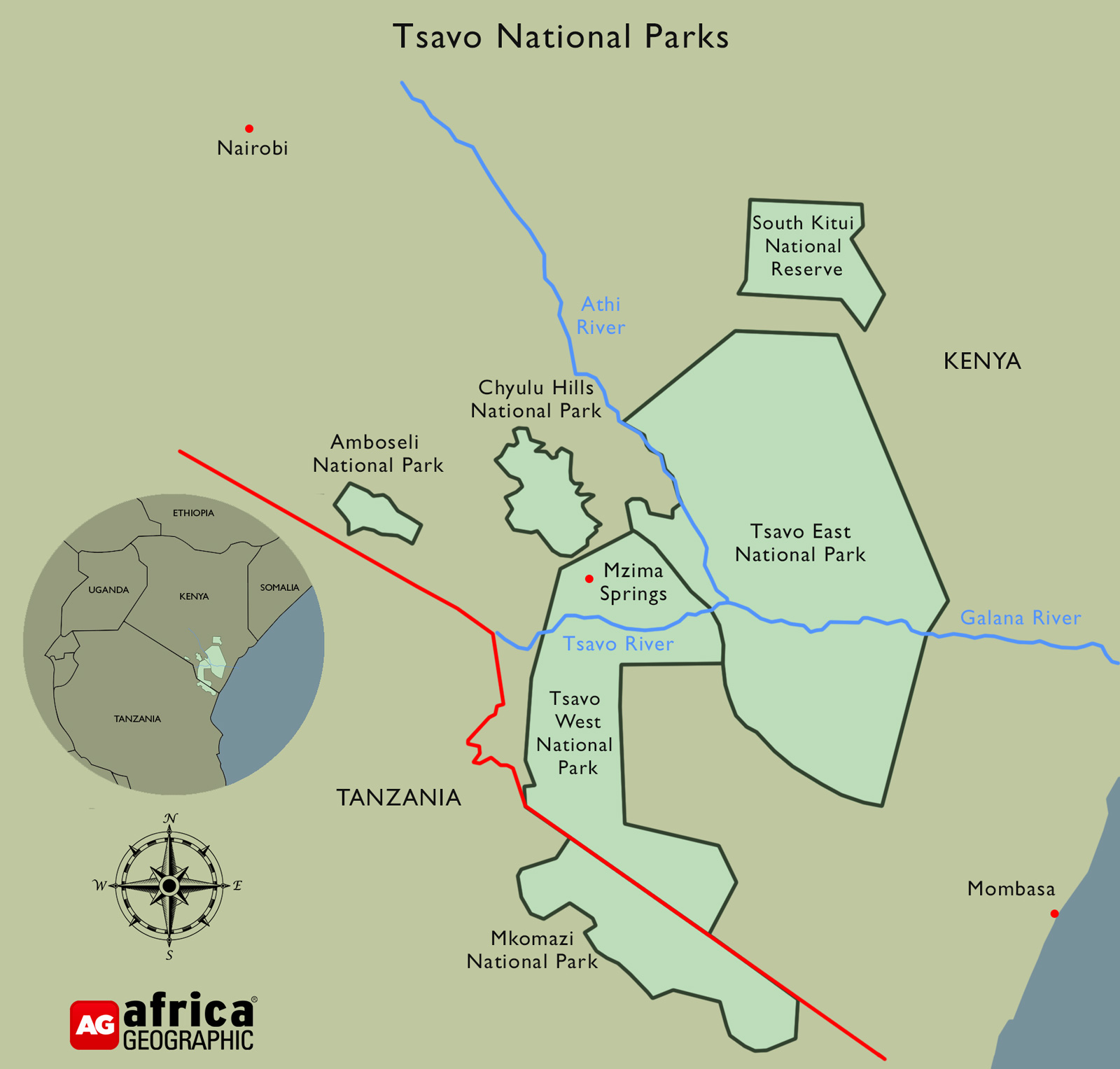

From untimely deaths to man-eaters and poaching wars, Tsavo has not had the easiest road, but now, combined, Tsavo East and West account for the largest of Kenya’s protected spaces by a comfortable margin, over 23,000km² (2,300,000 hectares), and one of the world’s largest protected wilderness areas. Named for the Tsavo River, which flows through Tsavo West before joining the Athi River to form the Galana River, this massive Big 5 ecosystem lies directly between Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, and Mombasa, the country’s main port city. This location is the reason behind the division of Tsavo East and West – they are split by both railways and the Nairobi-Mombasa Road, which sees the movement of around 50% of goods traded in East Africa. The enormous size of Tsavo makes it one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in Kenya, from the red semi-desert of parts of the East to the rainforests of the Chyulu Hills and everything in between.

Tsavo East

Tsavo East National Park is the larger of the twin parks, covering 13,700km² (1,370,000 hectares), and is also the more arid of the two. Apart from some crags around Voi and gorges along the Galana River, Tsavo East consists mostly of grasslands and savannas that stretch as far as the eye can see. The park receives fewer visitors than Tsavo West, and it is easily possible to spend a day exploring without encountering another soul. The reopening of the “forbidden zone” (closed off during the poaching wars) has added yet another spectacular aspect to an already striking reserve, particularly for those keen to spot African wild dogs (painted wolves).

Geologically fascinating, Tsavo East is home to the Yatta Plateau (the longest lava flow in the world, which begins near Nairobi and stretches for over 300km) and Mudanda Rock, which serves as a water catchment and offers visitors a perfect view of animals arriving to drink. Wildlife enthusiasts are guaranteed a glimpse or two of the long-necked gerenuks, one of the most peculiar-looking antelopes in Africa, and should keep their eyes peeled for the lesser kudu and fringe-eared oryx as well. Apart from the Kenyan-Somali border, Tsavo East is also the only place in Kenya to see the critically endangered hirola antelope, which were introduced there to help save the species. Sightings of black rhino are rare but rewarding, as are sightings of striped hyena. The bird variety is equally diverse, with over 500 bird species recorded in Tsavo East, including the golden-breasted starling, African orange-bellied (red-bellied) parrot, vulturine guineafowl and Somali ostrich.

Tsavo West

Tsavo West is more developed than Tsavo East, particularly the area accessible along the Tsavo River and the Mombasa highway. Close to the Tanzanian border and Mount Kilimanjaro, Tsavo West is topographically fascinating, and its dramatic mountains, inselbergs and sheer cliff faces are courtesy of ancient (and relatively recent) tectonic shifts and volcanic eruptions. As a result of fertile volcanic soils and higher rainfall, the vegetation in Tsavo West can be dense in places, which in turn can make wildlife viewing slightly more challenging, but the scenery is even more spectacular.

The Mzima Springs are a significant attraction for visitors to Tsavo West. Below the volcanic Chyulu Hills, a natural water reservoir percolates through porous rock before eventually emerging, filtered, as Mzima Springs. Here, people can enter a glass viewing chamber to watch life beneath the surface of a crystal-clear pool, including schools of fish, crocodiles, and the resident hippos. The dense date and raffia palms, along with an assortment of other fruiting trees, attract a variety of birds and primates, making the springs a veritable oasis, especially during the drier months.

Not far from the Chyulu Gate, the Shetani lava flow is a vast expanse of folded black lava from an eruption believed to have occurred only 200 years ago, now inhabited by nimble klipspringers and ubiquitous hyraxes, and (for the fortunate few), a lounging leopard unfazed by the sharp rocks. The nearby caves, formed by the same volcanic activity, can be freely explored by those brave enough to do so! The name “Shetani” translates to “devil” in Swahili, which offers insight into how the original residents felt as they watched the lava flow across the earth.

The Ghost and The Darkness

No description of Tsavo would be complete without mention of possibly the most famous man-eaters in history. During the construction of the Ugandan Railway and bridge over the Tsavo River, a pair of male lions, nicknamed The Ghost and The Darkness, stalked and killed many labourers. Despite efforts to keep the lions away from the camps by building large fires and bomas, the lions regularly found a way in and seemed to have no fear of people. Hundreds of workers fled, and construction was halted while Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson spent his evenings in a platform in a tree, attempting to bait and trap the lions before finally killing both. The number of people killed by the man-eaters of Tsavo is disputed – it seems likely that Patterson’s claim that they killed 135 people was exaggerated. Analysis of their fur suggests a number closer to 34 people, but it could not account for victims killed but not eaten by the lions.

There is no single accepted reason why those lions behaved as they did, and it was most likely due to a combination of factors and opportunism born of a different age. Certainly, at that point in history, the rinderpest outbreak of the late 19th century would have decimated their available prey, and one was shown to have a severe infection in the root of its canine tooth.

The experience

Visitors to Tsavo, particularly Tsavo East, should be aware that temperatures can be searing at times, particularly during the dry months between January and February and June to October. These consistently high temperatures are among the theories proposed to explain why all male lions in Tsavo have extremely undeveloped manes, though there is considerable scientific disagreement about the exact explanation. Either way, the baking days should be taken into account by anyone considering a visit to Tsavo.

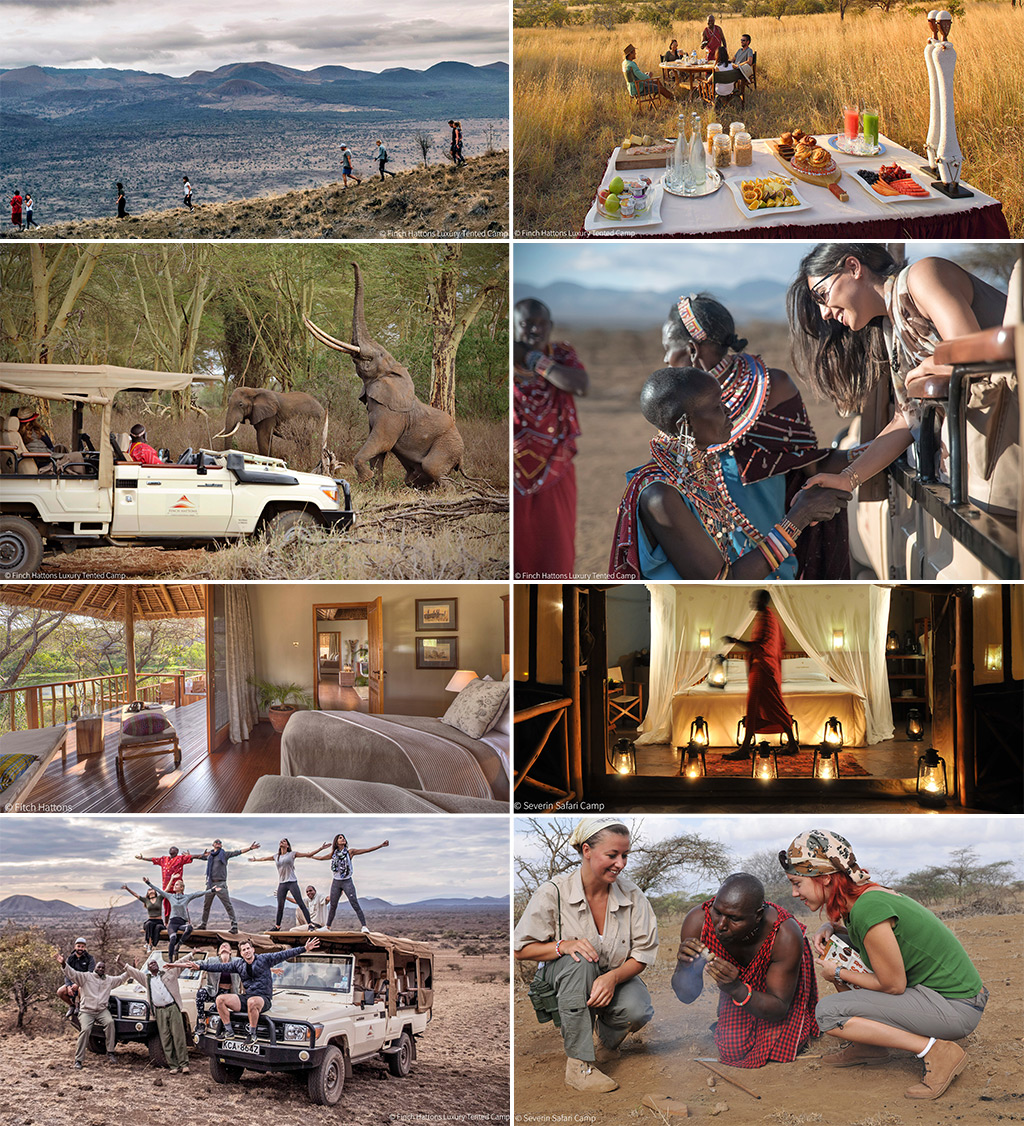

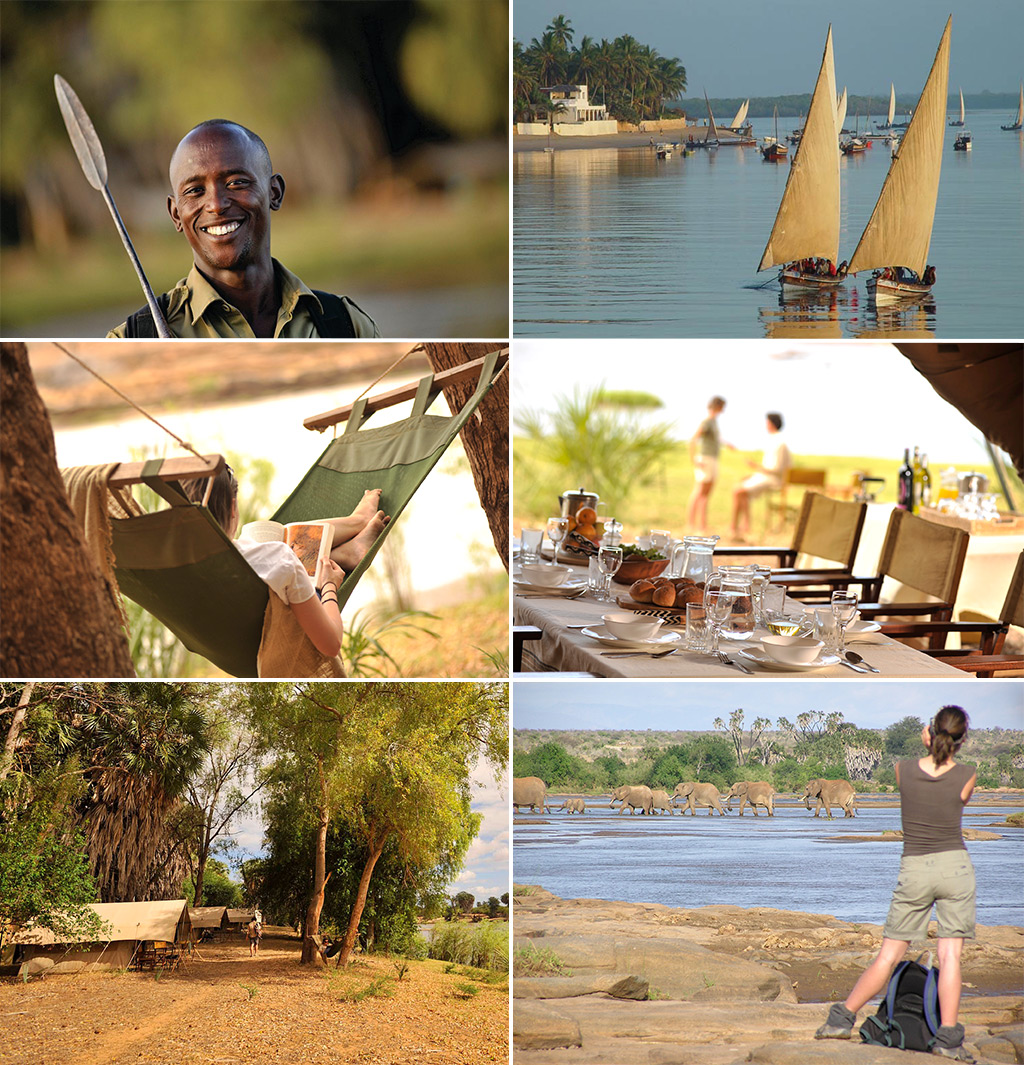

Many of Tsavo’s lodges are famous for their colonial-style luxury, and experienced guides are on hand to ensure guests experience the best of these remarkable national parks. Tsavo is enormous, and tourist density tends to be relatively low, so this is not a national park for novice safari-goers looking to be self-sufficient without adequate preparation. Those adventurous souls who do venture out should ensure that they are fully prepared, especially during the rainy season, when driving can be technical. Appropriate supplies of drinking water are a must!

Tsavo is famous for its herds of red elephants, including some of Africa’s last big tuskers, a testament to both nature’s resilience and the enormous effort that went into protecting them. Historically, Tsavo’s incidental proximity to the main transport route to the coast spelt disaster for its elephant and rhino populations during Kenya’s poaching wars of the 1970s/80s. Populations dropped to 5,300 elephants in 1988, but thanks to concerted conservation efforts, have since risen to around 12,000 today – one of the largest elephant populations in Kenya. For elephant enthusiasts, a visit to Tsavo is a must.

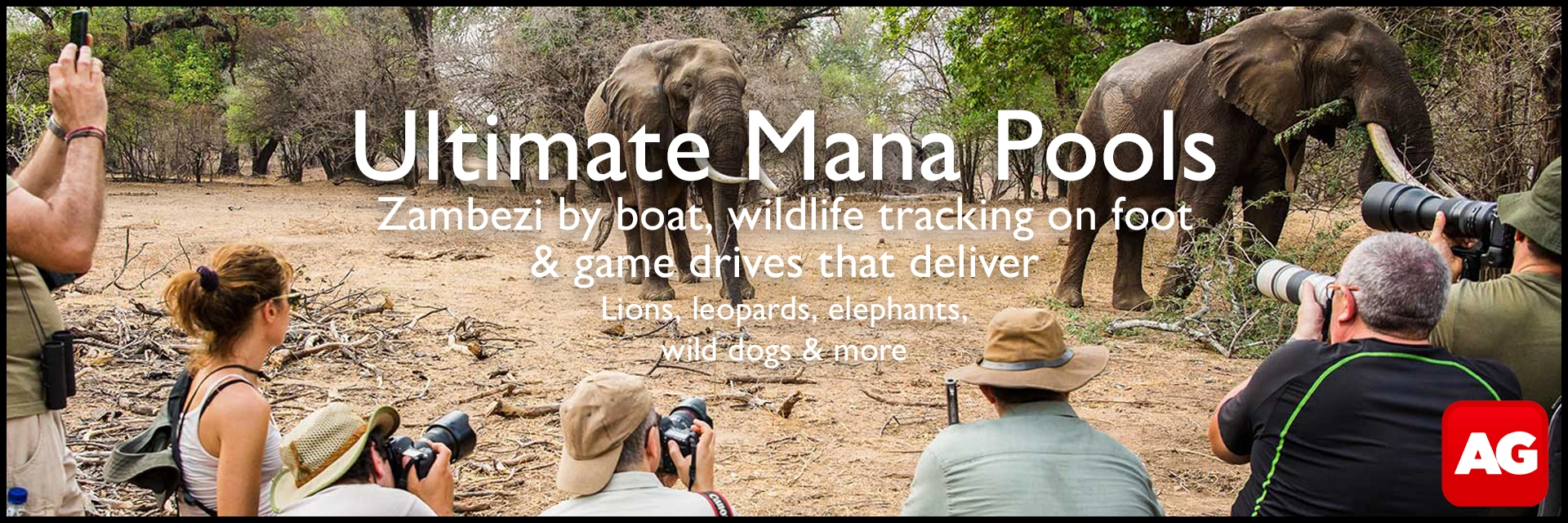

Those who have visited Tsavo can bear testimony to its unique feel and, without being too melodramatic, its profound and indelible impact on the soul. It is difficult to fully capture the Tsavo experience in words – the boundless skies and vast spaces combine with a rich sense of history to create a wilderness experience from a bygone era. For those who seek wilderness and enjoy elephants and bushwalking, try this exclusive safari option: Walking with giants in Tsavo

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()