Counting wild animals can be a complicated process, particularly when estimating populations in some of Africa’s massive protected wild areas. Yet policymakers and conservationists need to make the best possible decisions regarding the programmes put in place to conserve certain species, especially where limited budgets are available.

Consistent analysis is vital to monitoring population trends over the years and proactively identifying potential threats and problems, rather than attempting to rectify population declines after the fact. Now scientists working with Save the Elephants and Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) have shown how technology can be used to make aerial population surveys more accurate.

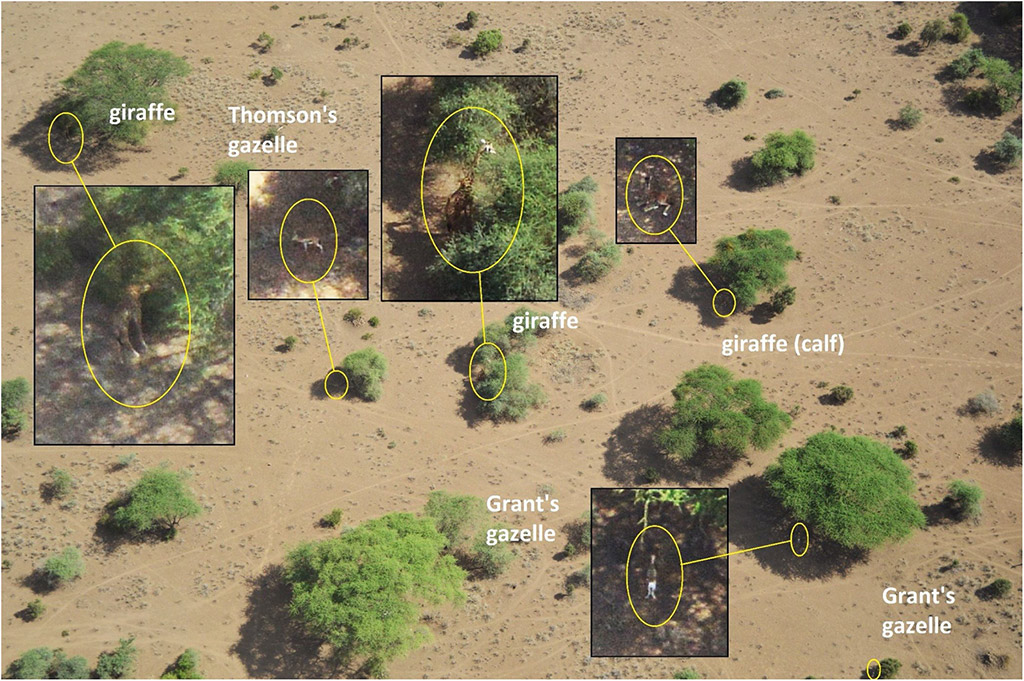

Typically, aerial wildlife counts are considered a more accurate method for counting animals, particularly in open spaces and where larger animal species are concerned. The standard method is to fly systematic reconnaissance flights over transects or along a survey line, with a ‘rear-seat-observer’ counting the number of animals within the transect or within a specific distance of the line. These numbers are used as sample units, and the population is extrapolated from there using various statistical methods. The researchers compared this method to a newly-devised ‘oblique-camera-count’ over Tsavo National Park. They concluded that human counters missed approximately 14% of the elephants, 60% of the giraffe, 48% of the zebra and 66% of the larger antelope. This, in turn, suggests that aerial counts have resulted in significantly undercounted wildlife populations.

This is not as a result of any negligence or lack of expertise on the part of the counters – animals can be hidden under dense vegetation, or cryptically coloured. Safety concerns mean that the plane has to maintain a specific altitude and speed, so counters only have a maximum of 7 seconds to count a particular area. Added to that is the inevitable variability as a result of aircraft type, ground speed, altitude, sample strip width and observer fatigue and the fact that using a helicopter to allow for more thorough counting is prohibitively expensive.

While these limitations had long been recognised, this is the first study of its kind where continuous oblique imagery (more suited to areas where animals might be resting under trees than imagery taken from directly overhead) was acquired over the complex terrestrial environments in Africa. Tsavo was chosen because wildlife counts had been planned for that period but it also presented challenges due to high ambient temperatures, strong winds and turbulence. The cameras were mounted to mimic the viewing perspective of the human counters. The images were later analysed by a team of interpreters who methodically worked through and enlarged thousands of images to identify and count animals.

At this stage, the authors of the study acknowledge that this process of image interpretation is labour intensive, as the interpreters went through over 200 images a day for nine months. Thus, they explain that this is just the starting point in the move towards more automated counting by machine learning where, at the very least, a software program can flag the potential presence of an animal. As technology improves, so will the ability to conduct aerial counts more accurately and cost-effectively.

As Save the Elephants has previously explained in an annual report, ever-changing technology has enormous implications for the conservation sphere. From specialised recognition software, scientists have already developed algorithms that recognise individual zebras and leopards. This information can only serve those tasked with protecting wilderness areas and the animals that call them home. Says Frank Pope, CEO of Save the Elephants: “Counting wildlife is critical for management but is expensive and surprisingly hard. Modern cameras mounted on aircraft can greatly improve accuracy, but counting the wildlife in the hundreds of thousands of images that result is impractical. Artificial intelligence holds the key to processing the images, and making these surveys cheaper as well as more precise. One day wildlife will be counted by drones and AI – what we’re doing is laying the foundations for that future.”

Resources

The full study can be accessed here: “Comparing an automated high-definition oblique camera system to rear-seat-observers in a wildlife survey in Tsavo, Kenya: Taking multi-species aerial counts to the next level”, Lambrey, R., Pope, F., Shadrack, N., et al, (2020), Biological Conservation

The Save the Elephants annual report referenced can be accessed here.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()