by Mike Pflanz with photographs by Kathy Karn

An agribusiness planning to operate an avocado farm in the Amboseli region – a water-stressed landscape of southern Kenya famous for its elephants – has lost its license after local Maasai and conservationists joined forces to protest the plans.

Kenya’s National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) revoked the license it gave to KiliAvo Fresh Ltd after questions about how the developer assessed the environmental impact its farm would have on the local ecosystem.

NEMA said concerns included: the proposed farm was in a wildlife corridor; that it violated official plans that zone the area for livestock and wildlife, not cultivation; and that the developers failed to consult widely enough on their plans.

Conservationists and communities stand together

Conservationists, including Big Life Foundation and Dr Paula Kahumbu, CEO of Wildlife Direct, worked alongside the Amboseli Land Owners Conservancies Association (ALOCA) to campaign against the farm.

“Big Life commends NEMA for following to the letter the relevant processes drawn up to balance development with environmental protection in circumstances such as these,” said Benson Leiyan, Chief Operating Officer for Big Life.

“The decision to reject KiliAvo’s insistence that it be allowed to continue operations sends a very clear message to anyone considering commercial farming in this area of Amboseli: only sustainable enterprises that fit with local land use plans and that conserve the environment for people and wildlife are welcome.”

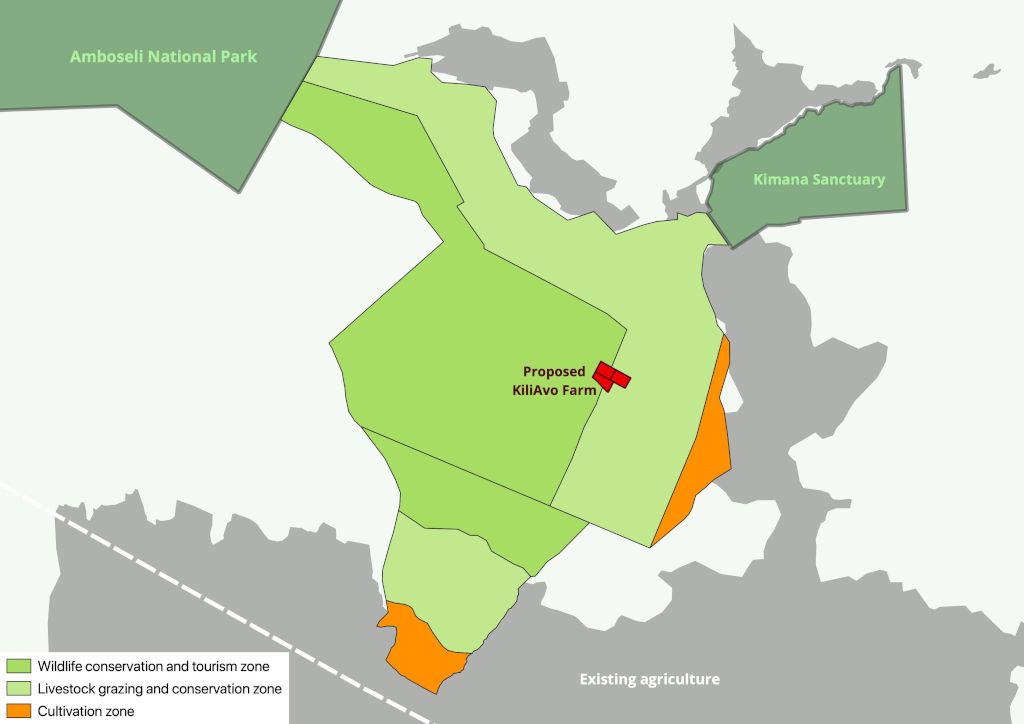

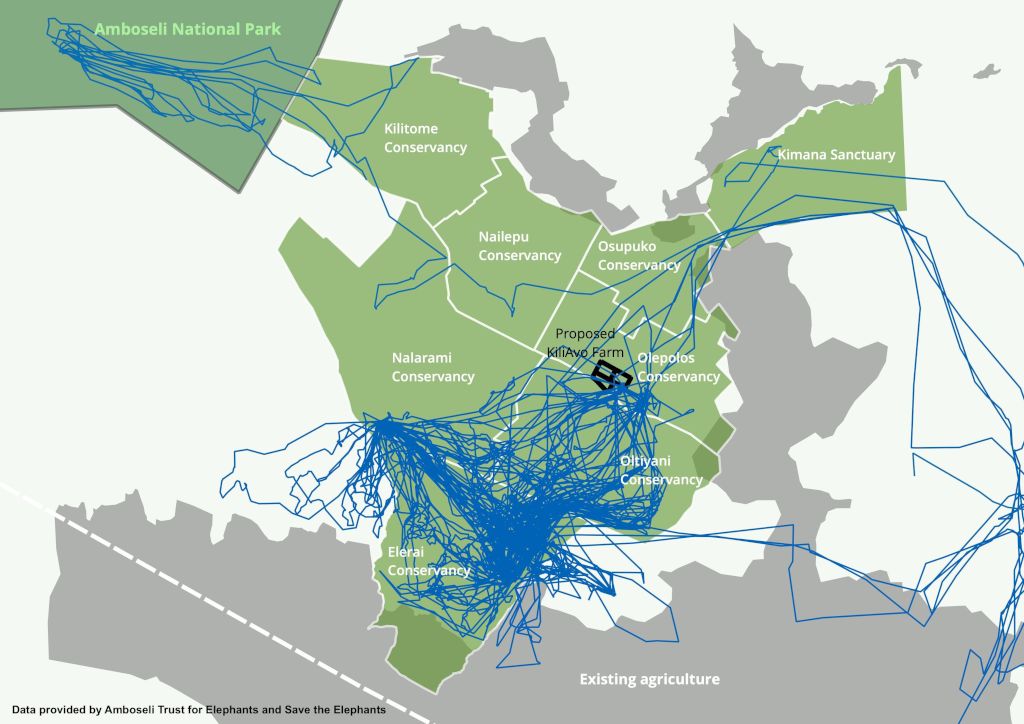

The farm sits in a buffer zone of wildlife habitat and Maasai grazing land just east of Amboseli National Park, a magnet for Kenya’s wildlife tourism famed for its herds of elephants grazing with the backdrop of Mt Kilimanjaro.

Tourism threatened

In 2019 close to 200,000 people visited the national park, generating millions of dollars for the Kenya Wildlife Service. KWS does not release exact figures.

But the park itself is small – at less than 400 square kilometres. To thrive, the multiple endangered animal species and the population of 2,000 elephants that live there need to be able to disperse and migrate through neighbouring, locally-owned rangelands.

Significant threats pressure this pocket of remaining wilderness in East Africa – habitat loss, agriculture and climate change are the principal ones.

Privatisation of communal land

After this previously communal land was subdivided into a patchwork of private titles, conservationists worked with the majority of the new landowners to group their plots into a series of community-owned conservancies.

Members pledged not to fence or farm their land, and in return, gain access to open rangeland to graze their cattle. Conservation and tourism operators pay regular fees for the protection of this crucial wildlife habitat.

However, there are a number of locals who chose not to group their land into the conservancies. Some have sold their land to people from outside the landscape, including speculators and brokers who, in turn, sold plots on to investors.

KiliAvo Fresh Ltd acquired their three plots of 60 acres each in this way, buying from a third party who bought them from the original Maasai landowners. There are no restrictions on buying or selling such plots.

There are, however, restrictions on land use plans agreed by the Maasai landowners’ association, ALOCA, for the immediate area and in the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan, for the wider landscape.

The ultimate land planning authority, the local county council, is overhauling its Spatial Plan but currently designates the area for “agriculture”. Initially, this was understood to mean cultivation but the chief lands officer from the council later clarified it was for “livestock grazing”.

This confusion, in part, led to NEMA issuing KiliAvo Fresh Ltd a license in August 2020 to develop 180 acres for growing avocados and other fruits and vegetables. This followed an earlier rejection of the same proposal, prompting critics led by ALOCA and the Kenya Wildlife Service immediately to cry foul when the new application was approved.

Samuel Ole Kaanki, chairman of ALOCA, said: “The majority of us are united against this farm because it could threaten water supply in this semi-arid place, block where we can graze our livestock, and deter tourism investors who pay us to bring visitors to see wildlife. These concerns were not addressed in the EIA, and we were very surprised to learn KiliAvo had been given a license.”

They complained that the license was issued without enough consultation with local people and environmental experts who would have objected, they said, because the farm stands squarely in an area zoned only for livestock and wildlife tourism.

Setting a precedent

Farm operations that encroach on wildlife land disrupt the natural balance of the ecosystem. Boreholes need to be dug for water-thirsty crops like avocados. These wells impact the water table, robbing surface water sources for wildlife and putting severe pressure on the groundwater resources and springs that support tens of thousands of people.

Faced with what it termed “new information and issues” that had come to its attention, NEMA ordered the farm to stop and threatened to revoke its license. The farm appealed that order at Kenya’s National Environment Tribunal (NET). After seven months of hearings, on April 26 the Tribunal dismissed KiliAvo’s appeal citing a lack of evidence or witnesses. The next day NEMA finally revoked the license.

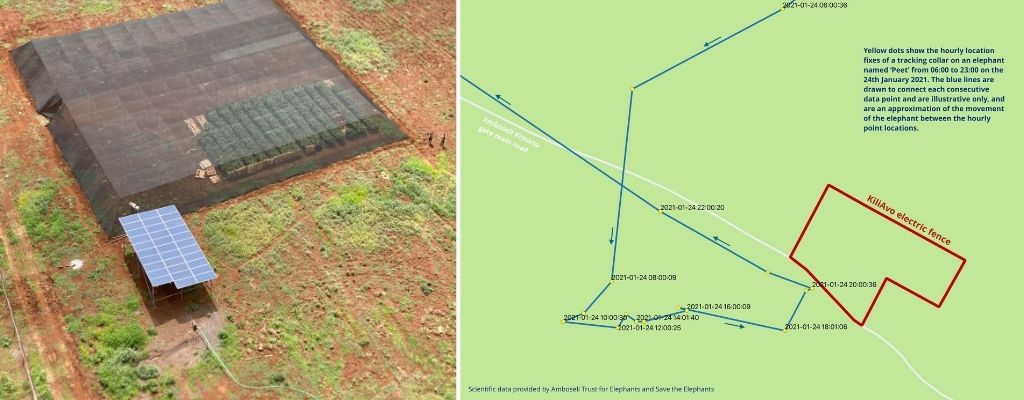

The farm’s owners said their 180 acres would have a negligible impact on the 38,000 acres of habitat in the Kimana Wildlife Corridor. Even if that were true – and it is unlikely – the key issue was that this case would have set a precedent and many other farms could follow, fragmenting the landscape and devouring essential resources like water needed by wildlife, farmers and livestock downstream.

Revoking KiliAvo’s license has been seen as a positive sign that Kenya is listening and seriously considering the health of an ecosystem and the concerns of local communities when dealing with the negative consequences of corporate-led agribusiness.

However, KiliAvo is expected to appeal these rulings. Conservation organisations including Big Life, KWS, the Conservation Alliance of Kenya, the Amboseli Trust for Elephants, Wildlife Direct, ALOCA, and tourism investors will remain vigilant in opposing KiliAvo’s plans for the farm and any other farming development that encroaches on wildlife corridors and pastoralist land use.

“This is not yet the end, we will continue until this farm has gone, and we are sure no others can follow it,” said ALOCA’s Ole Kaanki.![]()

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()