Africa's deadly beauty

All felids are beautiful. It is a shared trait made even more appealing by the uncanny impression that they are fully aware of their own allure. However, with its luminous eyes, bold facial markings and dramatic ear tufts, the caracal is arguably Africa’s most exquisite cat. Our appreciation of the caracal’s beauty goes back thousands of years, and historians believe that caracals were of considerable religious significance in ancient Egyptian culture, with sculptures guarding the tombs of pharaohs.

Introduction

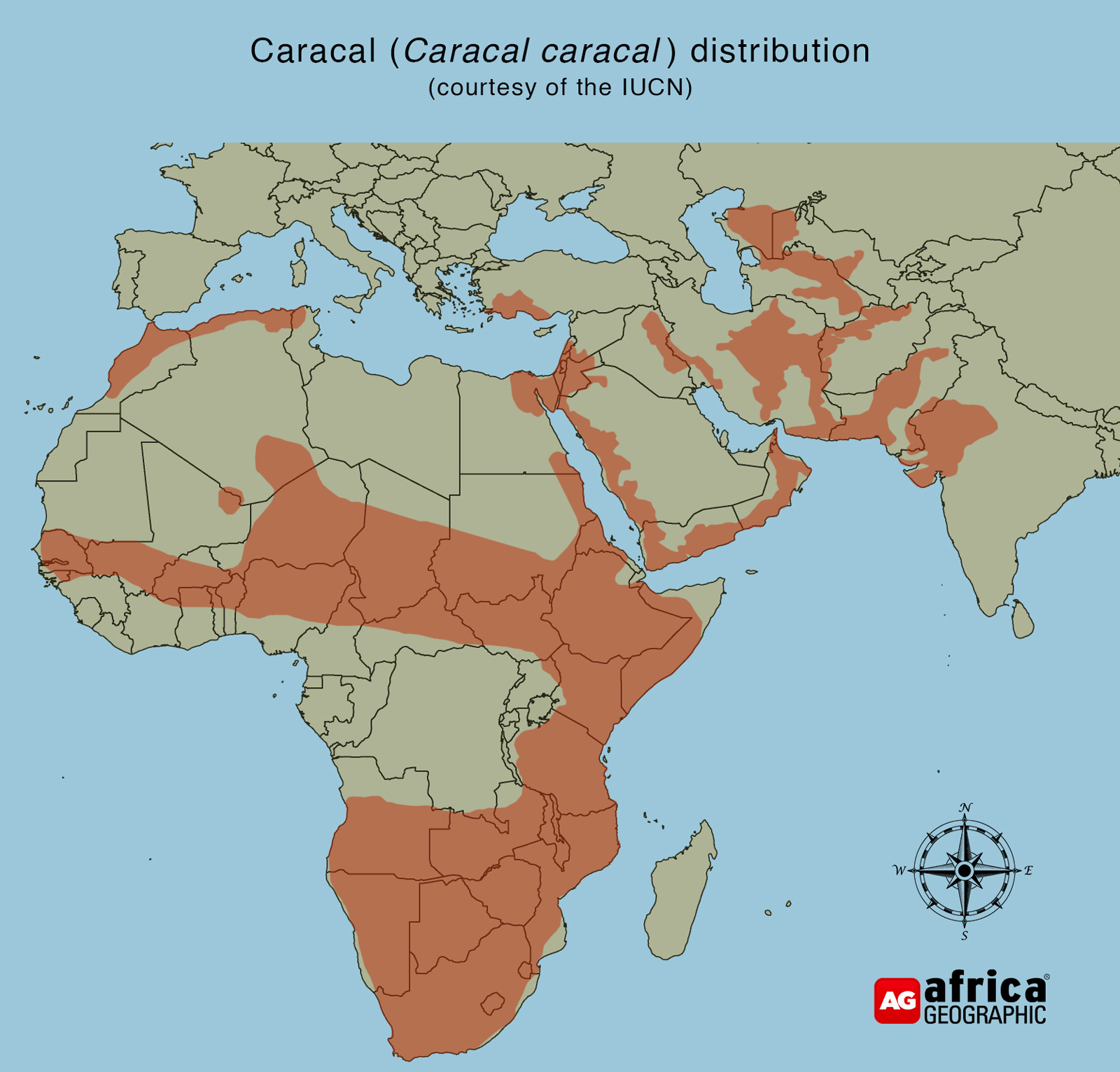

The caracal (Caracal caracal) is a medium-sized wild cat found throughout Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia. They are slightly stockier than their serval cousin, and their robust bodies are covered in a uniform coat of burnished red. Their bottle-green eyes are lined by the kind of natural eyeliner that would make Elizabeth Taylor jealous, with thick black lines running down the sides of their noses, emphasising the elegant jawline. The name “caracal” was inspired by their most distinctive feature, with the Turkish word “Karrah-ulak/coulac” roughly translating as “cat with black ears”. The outlandish ears combine with the caracal’s overall aesthetic to emphasise the impression of a proud and no-nonsense cat.

The tufted ears have led to the obvious comparison with the various lynx species, and the caracal is sometimes called the desert lynx. Phylogenetically, however, caracals are only distantly related to lynxes. Their closest relatives are the African golden cat (Caracal aurata) which inhabit the rainforests of Central Africa. Together with the serval (Leptailurus serval), these cats are all descended from the caracal lineage. Though not yet fully recognised on the IUCN’s Red List, the IUCN Cat Specialist Group suggest a tentative division into three subspecies: C. c. caracal of Southern and East Africa, C. c. nubicus of North and West Africa and C. c. schmitzi of Asia. Like the subspecies divisions proposed for the serval in the same report, these distinctions are based on a trend observed within other widespread mammal species. They could easily change with future genetic evidence.

The solitary and secretive caracal is found in a wide variety of habitats but shows a preference for more arid areas with suitable cover. In wetter areas, it is primarily outcompeted by the serval, while golden cats hold dominion over the central forested parts of the continent. Like servals, the caracal is usually classified as nocturnal, but in reality, they can be active at any time of the day, especially when the weather is cool.

Quick Facts

| Shoulder height: | 40-50cm |

| Mass: | 7-19kg |

| Length (not including the tail): | 71-100cm |

| Social structure: | solitary apart from mothers with kittens |

| Gestation: | 62-81 days |

| Life expectancy: | around 10 in the wild, up to 20 in captivity |

Setting the cat among the pigeons

Like all members of the cat family, caracals are efficient and deadly predators. They typically prey on small mammals and birds but can take down animals an astonishing two to three times their mass. Small they may be but beneath the sleek red coats are muscles of steel, capable of launching these agile cats more than three metres into the air. This prodigious pouncing power is shared with the serval but, while servals generally use these leaps to catch ground-dwelling rodents by surprise, caracals are experts at snatching up birds in flight. This is accomplished by a combination of exceptional depth-perception, an ability to twist and turn in the air, and proportionately enormous paws which spread open to expose needle-sharp claws.

The expression “to put the cat among the pigeons” may well be attributable to the caracal’s bird-hunting prowess. Until the 20th century, they were kept and trained by the Indian elite to hunt small game. In keeping with the human competitive streak, this inevitably resulted in a desire to test whose caracal was the better hunter. Caracals were set in arenas filled with pigeons, and bets would be placed on which caracals would kill the most. Unfortunately, like most wild animals caracals have been hunted for sport – even today.

Not just pigeons

Caracals are extremely versatile and adapt their hunting style to the habitat and type of prey. While the ambush approach typifies most hunts, they are adept climbers and exceptional runners. In fact, the caracal is probably one of, if not the, fastest member of the smaller cat species. They have been clocked at 80km/h, and while they are not endurance runners, their stamina is usually more than sufficient to chase down the prey of choice.

Small birds and rodents are dispatched by long canines and consumed immediately in their entirety. Larger birds and prey are killed by a bite to the throat and then carefully plucked. Caracals may stash exceptionally large kills for later consumption. They can extract most of their moisture needs from their food and are relatively water independent, though they will readily drink if water is available.

Catcalls

Though caracals’ social and sexual lives are still relatively understudied, they are known to be solitary and territorial. There is a considerable degree of overlap between territories, the boundaries of which are marked with urine and claw scratching. Like leopards, it seems that the territories of males are far more extensive than those of the females and encompass the territories of several different females. Territory size and caracal density are dependent on the resources available to them. When the habitat is suitable, and prey is abundant, the territories will be smaller, and the population density higher.

The bold facial markings and ear tufts are believed to play an essential role in visual communication within the species, but caracals also display a wide variety of vocalisations. These include a kind of twittering meow as well as growls, hissing and purring. Adult males and females only associate when the female is in oestrus, which the female advertises through frequent urination.

Caracal kittens

Caracals breed throughout the year, but most litters coincide with the arrival of the rainy season when prey is most abundant. The litters consist of anywhere between one and six kittens. The female will seek out an appropriate den site in dense vegetation or abandoned porcupine or aardvark burrows. Though born blind and helpless, the kittens rapidly transform into adorably fierce, tiny predators and start attempting to hunt around the den as early as three to four weeks old.

They are fully weaned by six months and reach sexual maturity early – between seven and ten months. However, they will likely only breed successfully after leaving their mothers at around 12 months.

Persecuted felines

The IUCN’s Red List currently classifies the caracal’s overall conservation status as “Least Concern”, but this is highly variable. Habitat loss and human expansion threaten most Middle Eastern and Asian populations, and caracals are thought to be close to extinction in North Africa. They are frequent victims of vehicle collisions and regularly come into conflict with livestock farmers.

Caracals are considered mesocarnivores/mesopredators – a loose grouping of medium-sized predators that include species such as foxes and jackals. These animals often prove to be highly adaptable to and tolerant of human encroachment. With the removal of competition from the bigger predators (who, by virtue of their size, are less resilient to human presence), such midrange carnivores seem to flourish. Unfortunately, this places them at a much higher risk of conflict with farmers. Caracals can and do kill livestock, though research shows that they prefer natural prey and that livestock is only utilised as a supplement.

As a result, in many parts of Southern Africa, particularly South Africa and Namibia, caracals are considered “problem animals” and are persecuted extensively in certain areas. As caracals are exceedingly challenging to count, the effects of this conflict are not fully calculated or understood. The Cape Leopard Trust currently has several research programmes to understand the extent of the problem and find solutions to mitigate it. Interestingly and almost counterintuitively, some farmers in parts of South Africa have been introducing caracals to their farms in the hopes of reducing stock losses. This is because caracals and black-backed jackals (also responsible for livestock loss) operate in direct competition, so the presence of one controls the numbers of the other – balancing out the system, essentially. The effectiveness of this approach has not yet been thoroughly evaluated.

Pet Caracals

Caracals are beautiful, they tame easily and are naturally expressive, which has led to surging popularity in the pet trade. Keeping pet caracals is a tradition that goes back hundreds of years in many parts of Asia, but today exotic pet breeders are flourishing. It should go without saying that caracals do not make good pets. Without thousands of years of domestication, the instincts of any wild animal remain close to the surface, and most end up in a rescue centre when the owner realises just how difficult to manage they genuinely are.

Where to find one in the wild?

Though they are widespread throughout Africa, the best places to see caracals are the more arid parts of Southern Africa. Here they are the dominant mesocarnivore, and sightings are far more common due to reduced vegetation cover. The Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park and Central Kalahari Game Reserve boast excellent sightings, as do many of the parks in Namibia.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()