On a recent trip to the Cederberg with my 9-year-old son, I arranged to meet a young researcher working for the Cape Leopard Trust. I was keen to chat to her about the work of the CLT on caracals, and to try and expose my son to the blood, sweat, mud and tears side of scientific research and data gathering.

Unfortunately, on the day we had set aside to hook up, a fairly vicious cold front whipped in over the mountains, and the usually red-tinged rocks were being lashed by icy wind and rain. Our little mountain hut at Driehoek became the only viable warm, dry meeting place.

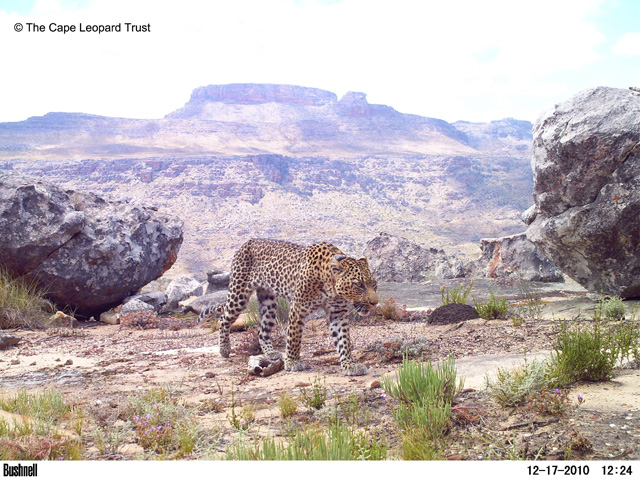

The diminutive, bubbly, French-speaking Marine Drouilly spent well over an hour with us, and we all huddled around her laptop, looking at all the incredible images from the various camera traps and learning all about her work.

The main objective of Marine’s project is to study the spatial and behavioural ecology of the caracal (Caracal caracal) in a fairly extensive area of the Cederberg, including the Cederberg Conservancy. Very little has been published about this elusive species, particularly concerning interactions with the area’s apex predator, the Cape leopard (vital natural regulators of caracals).

Armed with up-to-date data and knowledge, effective conservation and management strategies can be designed and implemented. With a more solid understanding of the way these two species interact (with regards to interspecific behaviour, habitat use and prey preferences); it is more likely that local farmers will come to understand how critical it is to maintain ecological balance. Marine pointed out that there is a real paucity of data addressing even the most basic ecological questions for many of the smaller predators, not just caracal.

Thanks to almost a decade of tireless work by the Cape Leopard Trust (and with the support of local farmers), the level of leopard persecution by farmers has diminished significantly in the Cederberg.

It is fairly well known that livestock farmers throughout southern Africa are less than partial towards caracals or ‘rooikat’ and they are very often persecuted because of the suspected damage to small livestock. Tragically, these beautiful cats are even classified as ‘problem animals’ in this country – along with jackals, badgers and genets. Beyond the Conservancy boundaries, caracals frequently come into conflict with farmers, where livestock become opportunistic prey items. In most natural areas, natural prey animals are still available to these cats.

Marine went on to explain that the caracal is considered a ‘mesopredator’ – a term that refers to its trophic ranking. What is important in this study is to get a handle on what would happen if the apex predators were persecuted to the point where they were removed from the system. Would there be what scientists dub ‘mesopredator release’? There are catastrophic examples of this from all over the world – from the removal of wolves in Asia, bears and wolves in North America to lions and wild dogs here on our continent. Such negative impacts on apex predators can have devastating ecological consequences. The ripple-down effect can often lead to an increase in populations of the mesopredator, which, in turn, can negatively impact the ecology of the prey species.

So just how will Marine be tackling this big research question? How does one search for and analyse the proverbial needle in a haystack? These animals are notoriously difficult to study given their elusive, nocturnal habits. Through a painstakingly slow process of capturing and collaring animals (with GPS devices), vital data on their movement can be gathered, and mapping can begin to take place. Plotting movements, verifying how feeding ecology compares to other species and establishing the extent of their home ranges all form pieces in the giant ‘caracal jigsaw puzzle’. Once the pieces are put together, it will then be possible to find and suggest practical solutions to reduce the inevitable human-wildlife conflicts that play out between caracals and farmers.

Marine has been working in the area since March 2012. What struck me about Marine is her real love for these much-maligned animals. This is no hard-arsed researcher – here is a soft-hearted soul who really wants to be sure that the animals do not suffer at all in the process of data gathering and she makes sure that the safest possible capture techniques are used (and has gone so far as to try out one of the methods on herself!)

Marine explained that CLT’s founder, Dr Quinton Martins, began collaring caracal in 2008 to assess the feasibility of conducting a full-blown study on the species. Martins and his team collared 3 male caracals before Marine’s arrival. The team have since managed to collar a female.

The data gleaned thus far shows that territorial male caracals can have ranges that extend as far as 100 square kilometres! They have also established that caracal prey ranges from klipspringer, grey rhebok, grey duiker, grysbok, dassie, bat-eared fox to (surprisingly!) black-backed jackal. What I found particularly fascinating and pertinent was that of the 21 caracal kills located in 2009 using GPS points, only one was a lamb. Food for thought, indeed.

Marine also showed us an impressive collection of photographs taken with the dozen or so cameras that have been placed in the field. From large and small-spotted genets leaping high into the air in response to the flash, to curious baboons with their noses pressed up against the lens, aardwolf, porcupine, African wild cat, honey badgers, nightjars and even a striped polecat. Getting up close and personal with the hustle and bustle of the Cederberg night prowlers was a rare treat indeed.

The Cape Leopard Trust is the main sponsor of Marine’s caracal project. The use of the research vehicle, the 4 GPS collars, fuel and traps are all courtesy of the CLT. When you consider that a single collar costs R 20 000 and a camera can cost up to R 3 000, this is no walk in the park when it comes to funding needs! Very often, the cost of research equipment is what limits the extent of scientific research. The project recently received funding from the Wilderness Wildlife Trust to cover the veterinary fees.

What is truly heartening about this project is how farmers and landowners in the area (particularly in the Conservancy) have allowed for studying a self-regulating population of caracal and leopard over the years. This project stands as a real beacon of hope and an example of how (with just the right level of intervention) landowner attitudes and behaviour can shift and human-wildlife conflict can be avoided.

Read more about the rooikat here.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()