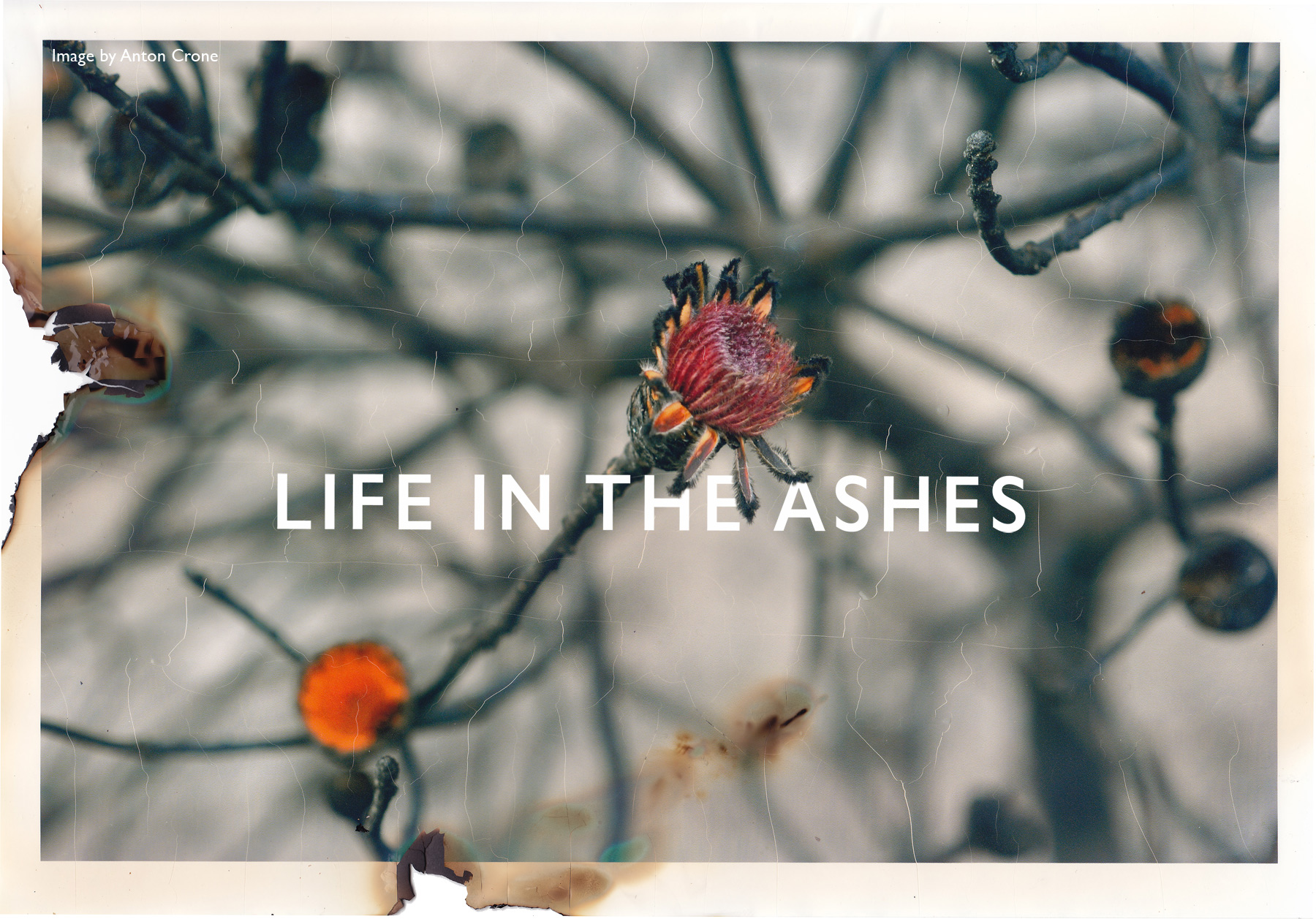

RISING FROM THE FLAMES IN TABLE MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK

Walking through the ashes of Table Mountain National Park after last week’s monumental fire, I didn’t expect to see it as a landscape teeming with life, and yet it was. The sensation was one mixed with awe at the devastation and wonder at the nature that has survived or is already emerging. The fire raged through 5,500 hectares of the Cape Peninsula for five days with strong winds and extreme temperatures making it difficult for firefighters to control. Table Mountain National Park was by far the most affected area, a pristine environment which is home to about 2,000 species of plants – more than the entire British Isles.

But as I walked between the blackened fynbos on Silvermine, I saw a rock kestrel hovering above, no doubt tracking a rodent exposed by the lack of foliage; succulent green shoots pushed up through the ash at my feet, and pink proteas were poised to blossom at the end of roasted stems.

Trails probably left by a leaf borer feeding on a leucodendron leaf. ©Christian Boix

A live tortoise which miraculously survived the rapidly advancing flames.©Christian Boix

Fire is a rebirth for the ecosystem, without which the system winds down and dies

Christian Boix, teamAG’s safari director and resident ornithologist, met up with me after walking in the opposite direction, towards Muizenberg. He had seen a peregrine falcon and an African marsh harrier, the latter unusual in this region, probably having flown in to capitalise on vulnerable prey. White-necked ravens had also arrived to scavenge and clean up the show. He showed me pictures of a live tortoise – a relief from the images of dead ones too encumbered to escape the flames – and he showed me insects working the flowers and millions of seeds which have been scattered after the flames.

‘When we get a fire like this, our instinctual reaction is to feel a lot of sadness for losing our flora and fauna. But this flora is adapted to burn; it needs to burn to live,’ said Dr Adam West from the Department of Biological Sciences at UCT in a radio interview last week. ‘If fynbos doesn’t burn every 15 years or so, we lose a lot of species, we lose a lot of diversity from the system, and the system effectively starts to wind down and die. Fire is really important. It’s really a rebirth for the ecosystem.’

I’m excited at the opportunity to witness this rebirth: not far beneath the soil, dormant seeds triggered by the heat await the coming rains; burrowing animals and insects are re-emerging, and birds are flying in to claim them. Ants scurry to reach seeds they will bury for food, aiding germination, and rodents race to beat the ants to it. But this is my layman’s sense of it.

The Lottery of Fire

As fynbos specialist Prof. Richard Cowling explains, a big lottery is currently at play. ‘There’s a lot of sorting going on right now in how fynbos regenerates. We’ve had a fire that raged over four or five days, and in some places, the wind-driven fire went into old, dense bush. The intensity would have been phenomenal. That would have had a very different effect on regeneration to another area where the veld was less dense, and the fire was burning on a cool day.’ Indeed one of the fire days was cooler and even brought some rain. In contrast, on the day before, Cape Town recorded its hottest temperature in 100 years, at 42 degrees celsius.

‘A really hot fire stimulates germination of your large species’ seeds, like pincushions and buchus, that have been buried in the soil. Some might have been waiting for 50 years,’ he adds, recounting the story of a species thought extinct that suddenly re-emerged after an intensely hot fire. ‘But your smaller seeded species, your ericas and daisies, get absolutely singed by this heat, and that is why fynbos is so bogglingly diverse: each fire is unique in its effect on the species. It’s a lottery, a random process. You can’t predict what the fire is going to be like. And what happens after the fire is so important.’

The timing of this latest fire has been perfect for many of the plants, occurring as it did just before the rainy season. The taller plants like proteas and leucadendrons that release seeds after the fire are favoured if the rains arrive soon. But if the fire had occurred in September, for example, these seeds would lie on the soil surface right through the summer, where they can be scattered by wind and eaten by rodents.

Life pushes up through the ashes of Silvermine. ©Christian Boix

Many species of protea seeds are adapted to be scattered by the wind. ©Christian Boix

The plants gamble with their seeds. Sometimes they hit it big, sometimes they don’t

‘If we get good winter rains starting in April, then that complement will germinate well. But that has another implication. You get a really dense over-story of proteas and leucadendron which selectively suppresses the plants in the understory.’ This shading out of smaller plants means it is cooler there, and plants producing seeds dispersed and buried by ants will suffer because ants don’t venture into cool areas. Conversely, rodents like living under proteas because it is cool; it provides them with shelter from raptors and food in the way of seeds. So when the next fire comes, even if it is intensely hot, there are not enough of those hard seeds available for germination.

‘Ultimately, this is a complex process,’ says Cowling. ‘The plants gamble with their seeds. Sometimes they hit it big, sometimes they don’t, and there’s a local crash in the population. It’s that up and down in populations with each fire that enables this huge number of species to coexist in this small region of the Cape Peninsula.’

The Winners and Losers

This “gamble” applies to flora, insects, and animals that thrive on the fynbos in all its incredible diversity.

‘Fire takes everything down to its bold, most naked competitive arena. It’s a fight for limited resources,’ says Dr Phoebe Barnard of the Birds & Environmental Change Program at the South African National Biodiversity Institute.

She explains that birds are going into the burnt area as opportunists, birds of prey like buzzards and goshawks, which capitalise on vulnerable mammals, and herons and hadedas, which capitalise on insects. Then some birds can feed for a long time in “roasted” areas, like cape canaries which feed on the seeds of leucodendron bushes, often roasted in their little cones. ‘I suppose it’s like having toasted sunflower seeds,’ she adds.

A Cape turtle dove surveys the landscape in search of fresh seeds. ©Christian Boix

The king of proteas takes a roasting. ©Anton Crone

Some birds have evolved to respond to fire by making use of nectar resources elsewhere

‘You’ve got winners and losers in a frequent fire. The winners tend to be some of the fynbos endemic species like the Cape rock-jumper. Birds like them do very well because fire exposes the ground, the birds clean up any insects injured or killed by the fire, and for the next four or five years, they’ve got a relatively open habitat of newly growing fynbos. One of the losers might be something like the Cape sugarbird, which requires mature proteas and Proteoideae, such as pincushions, to be able to drink nectar. They cannot rely on things that come up in the new fire age, so they have to go elsewhere.’

Barnard studies the movement of fynbos endemic bird species in such events. Each of the six endemic fynbos bird species has a different movement strategy. Some of these birds hang around in their territories, like the orange-breasted sunbird, and they are very vulnerable to fire. But the Cape sugarbirds move on, sometimes very long distances. Like them, some birds have evolved to respond to large-scale fire by using nectar resources elsewhere; others are less evolved in that way.

They have found that over the past 10 or 15 years, more birds have been moving down into the suburbs in the event of a fire. The sugarbird has an unfortunate name as the association might encourage more people to place sugar water feeders in their gardens after fires to help the birds. ‘I have mixed feelings about this,’ says Barnard. ‘I feel the way people provide resources for wildlife is, on the whole, a negative thing because it creates a dependency. Doing so alters movement patterns, survival patterns, health and disease vulnerability.’ Barnard stresses that she is not talking only about fynbos endemic birds but species in general. ‘But at the same time,’ she says, ‘we have manipulated the area around natural fynbos, and we have caused more fires than is natural, so we cannot help but try to compensate by providing food in the event of such a large scale fire.’

What you can do to protect species in the event of fire:

In the Cape Town suburbs, Barnard encourages people to plant more locally indigenous water-bearing and flowering species for the long term. Only if they cannot, and only in the short term, should people provide nectar bottles and feeders for birds, making sure not to provide artificial sweeteners of any kind, including xylitol, because they can kill sugarbirds.

West says we can help in the event of a fire by protecting the natural system, such as stopping the encroachment of houses into the fynbos and stopping the propagation of alien vegetation that adds significant fuel to the fire and risks it running completely out of control.

Fynbos involves thousands of species. It’s not just proteas; it’s birds, insects, reptiles and mammals. ‘Some are winners, and some are losers, but we must cater for all of them by keeping a mosaic in the landscape,’ says Barnard. This ideal would mean a landscape of fynbos at differing cycles of fire age so that all species can thrive by moving easily between habitats.

The ideal is a mosaic landscape of fynbos at differing cycles of fire age

But we humans are a crucial species. The fynbos has survived for more than 3 million years. Lightning would have been the key factor in starting fires back then, and humans have been starting fires here for at least 200,000 years. You can say we are part of the system. But a fire that occurs too frequently or in the wrong season means that plants do not have time to seed or the seeds are wasted, eliminating species, including plants, birds, insects, reptiles and mammals. It’s a heady responsibility for our species.

I often speed over Silvermine on my way somewhere else, ignorant of the incredible ecosystem on either side of the road. But I will spend more time here, and I look forward to seeing new life take hold. One of the most rewarding sights on Silvermine was seeing a different aspect of life in the ashes: two young boys clearing up the broken bottles that were once hidden by the undergrowth, now revealed by the flames.

Dedicated to all the firefighters and volunteers who worked tirelessly to contain the blaze, and to the memories of helicopter pilot Willem “Bees” Marais and firefighter Nazeem Davies who died in service to the Cape of Good Hope.

Contributors

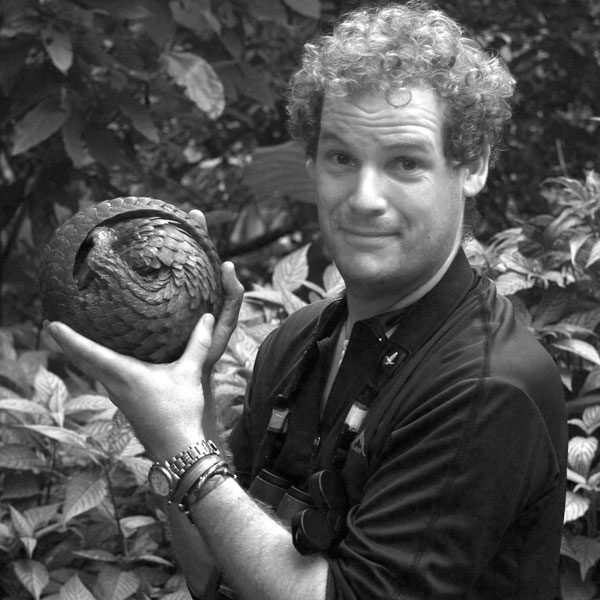

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, and drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton has a strong empathy with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote, environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, and drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton has a strong empathy with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote, environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

CHRISTIAN BOIX left his native Spain, its great food, siestas and fiestas. He now works in teamAG – as a safari consultant and Director of the company.

CHRISTIAN BOIX left his native Spain, its great food, siestas and fiestas. He now works in teamAG – as a safari consultant and Director of the company.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()