AFRICA'S RAREST PARROT

![]()

South Africa’s remaining Mistbelt forests make up less than 0.15% of the country’s total land area, and less than 5% of these forests are under formal protection. They are small and fragmented, increasingly divided by the steady and persistent advance of human progress. Small though they may be, these forests are biodiversity hotspots in South Africa, home to some of the country’s most unique and unusual plant and animal life. One such creature is the Cape parrot. It is South Africa’s only endemic parrot species, and there are believed to be fewer than 2,000 left.

Introduction

Like all members of the Psittaciformes (the parrot family), Cape parrots are charismatic little characters; brightly coloured and intelligent. Similar in size to the African grey parrot (but with a larger beak), they measure between 251-349mm in length and weigh between 260-329g. While they are predominantly green in colour, the outer edges of their wings and shoulders are highlighted in vivid orange. They are occasionally mistaken for the more common and widely distributed grey-headed parrot (more on that later) due to the brownish feathers around the head and neck, though this colour can vary from olive-yellow to a golden brown. The juveniles and females have a bright orange patch of their foreheads, which the males typically lose upon reaching adulthood.

The parrot and the yellowwoods

While they occasionally do frequent other habitats, the lives of Cape parrots centre around the Mistbelt forests which are dominated by yellowwood trees and, as a result, the future of these parrots is intricately linked with that of South Africa’s national tree. Yellowwoods are large evergreen trees which may reach over 30m in height and, while lightweight, the wood is hard and durable. These characteristics meant that yellowwoods played a significant role in South Africa’s version of the industrial revolution, with millions of trees historically harvested for railway sleepers, mining, floors, wagons, and furniture. Today yellowwoods are officially protected, but the wood is prized for its quality and colour, making it one of the country’s highest-valued timber trees.

Cape parrots have the most specialized diet of any of their family members and show a distinct preference for yellowwood fruit kernels, though they will also feed on the kernels of other fruiting trees in the forests. They are pre-dispersal seed predators, and their powerful beaks crack open unripe kernels at a stage when their avian and mammal competition would find these unpalatable and inedible.

The fruiting of yellowwoods and other tree species varies and, as a result, Cape parrots are “food nomads”, sometimes flying up to 90km per day to find food. When other fruit resources are scarce, they have been known to feed on exotic species such as the seringa, jacaranda, and the black wattle, and will feed on protea flowerheads at certain times of the year. They have also been observed foraging in coastal forests and opportunistically feed on crop species like pecan nuts, which naturally puts them at risk of conflict with farmers.

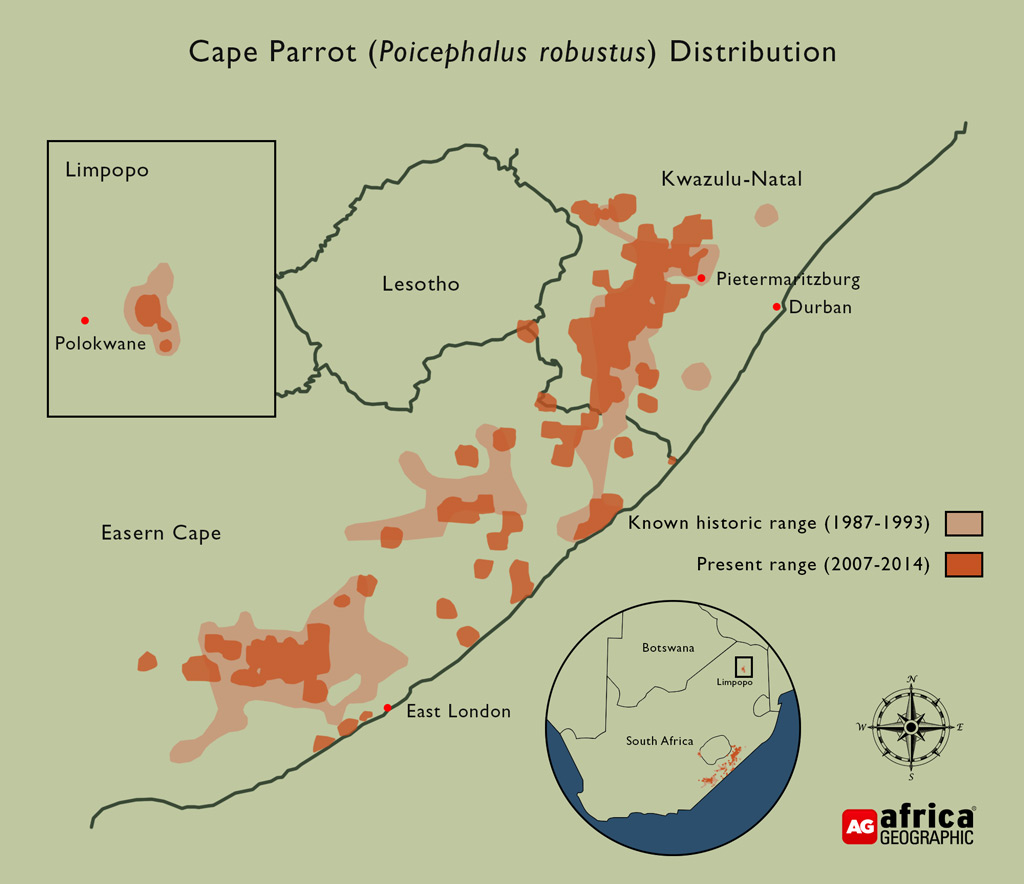

The specialist dietary and breeding requirements of the Cape parrots means that their range is restricted to the mosaic of remaining Mistbelt forests in Eastern Cape and KwaZulu Natal, with a small population in the forests of Magoebaskloof in Limpopo. Research has shown that there are three genetically distinct subpopulations: one in the Amatole mountains in the Eastern Cape, another which ranges from Engcobo and Mthatha in the Eastern Cape to the midlands of KwaZulu Natal and the isolated population in Magoebaskloof.

Birds of a feather

Cape parrots have been recorded to live for over 30 years in captivity and breed for the first time between 4 and 5 years old. Though they may gather in large flocks of up to 70 or more individuals around suitable roosting sites on the higher ridges of the forest, Cape parrots are solitary nesters with peak breeding occurring between August and February. The eggs are incubated for between 26-30 days, and both parents play a role in caring for the chicks. Once the young parrots have fledged (between 55-79 days after hatching), the young remain with their parents, and they often move around in family groups before joining large juvenile flocks. Vocal communication between family members and other parrots is almost continuous throughout the day, particularly in flight.

Cementing their reliance on yellowwoods even further, Cape parrots also prefer to nest in yellowwood trees, utilizing cavities or holes made by other bird species and in dead portions of mature trees and often returning to the same nest in subsequent years. Research also indicates that their chicks are fed on a diet consisting almost exclusively of yellowwood kernels.

The Innominate Parrot

Of all the parrot genus divisions, the genus Poicephalus is the most species-rich and widely distributed in Africa. The classification of the Cape parrot (Poicephalus robustus) has historically been the cause of significant contention within the scientific community, and it was only recognized as an individual species on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2017 based on a decision by BirdLife International. Before that, the species P. robustus was considered to have two subspecies: the grey-headed parrot (now P. fuscicollis suahelicus), the brown-necked parrot (now P. f. fuscicollis).

The taxonomic revision was based on an examination of differences in habitat usage, body size and morphology and behaviour. Although the revision was not based on genetic data, a genetic study by South African scientists which suggested the two taxa had diverged more than 2 million years ago did prompt BirdLife to take a second look. As in any situation where a species/subspecies division is under consideration, the classification of the Cape parrot as a separate species allows policymakers and conservationists to shape management strategies to protect them better.

Conservation consequences

The change from subspecies to species on the Red List required the allocation of a conservation status, and the Cape Parrot is now considered to be ‘Vulnerable’ based on the fact that while the total population is small, the numbers seem to be relatively stable. However, within South Africa, the 2015 Eskom Red Data Book of Birds allocates the Cape parrot a local classification of ‘Endangered’, with the authors suggesting that in the next two generations, the population will have decreased by at least 20%.

The Cape Parrot Big Birding Day

The Cape Parrot Big Birding Day, an initiative of the Cape Parrot Working Group, began in 1998 and has been held on one day every year in April and May. Every year, volunteers gather at various appropriate sites to count birds and aid researchers in counting parrots, making this one of the longest-running citizen science projects in South Africa. As its popularity grew, more and more observers joined the process, and the first few population estimates increased dramatically from around 500 to over 1000 individuals before stabilizing at approximately 1,600 or so individual parrots. In 2019, the Cape Parrot Big Birding Day yielded the most extensive ever population estimate of 1,804 across the entire range. The 2021 count yielded 1,477 parrots.

The threats

Habitat loss and fragmentation are the primary threats to remaining Cape parrot populations, though much of this damage was done before 1940 at the height of the logging of forest hardwoods. However, in some parts of the Cape parrots’ range, logging continues, especially of dead yellowwoods, which are their preferred nesting sites. An increase of non-indigenous trees (mainly pine) has also played a role in threatening Cape parrot populations. The knock-on effect of this logging and the degradation of natural habitats is a shortage of food. As mentioned earlier, fruiting in these forests tends to occur in “patches”. In the past, the forests would probably have been large enough that the parrots would simply move from place to place, but there are now times during the year when they are forced to seek food elsewhere, occasionally in orchards and farms.

While a robust breeding industry supplies the legal trade, Cape parrots are valued in the illegal wildlife trade, as is the case with all parrot species. The extent of this particular threat has yet to be quantified, but there are reports of birds being lured using bird calls and nestlings being harvested to supply the illegal trade.

Another major threat affecting both wild and captive Cape parrots is Psittacine Beak and Feather Disease (PBFD), caused by a Circovirus which is believed to have originated in Australia. The disease may cause abnormal feather growth and the loss of normal feathers, as well as painful sores around the bill, and in acute cases, there is only a slim chance of recovery. The birds have been observed to be particularly susceptible to the disease during times of drought when food resources are limited, and severe outbreaks have the potential to cause serious harm to the remaining populations.

Emerging threats

As if the Cape parrots did not have enough to contend with, researchers have also identified two major emerging threats to their future stability. The first is climate change, which is likely to impact almost every fauna and flora species on the planet but particularly specialist species with a small population and restricted distribution. The second comes in the form of a threat to Mistbelt forests and, in particular, the tree species utilized by the parrots. The polyphagous shot hole borer (Euwallacea fornicates), native to south-east Asia, infects host trees with a fungus which spreads through the tree’s internal transport system, eventually blocking it and resulting in the death of the tree. The borer has spread rapidly through South Africa, and 43% of the tree species affected by it are feed on by Cape parrots.

A Plan of Action

In September 2019, the country’s foremost experts in Cape parrots and their conservation held a workshop to develop an Action Plan to guide future and ongoing conservation efforts of the Cape parrot, incorporating new research and information and building on previous action plans. Amongst others, representatives from the World Parrot Trust, the Cape Parrot Working Group, BirdLife and the Endangered Wildlife Trust were in attendance to share their expertise and experience. The report from the workshop details extensive assessments of the threats facing the parrots both now and in the future, and details what actions will be taken and how responsibility will be delegated.

The Action Plan links the conservation of the Cape parrots to the protection of their vital habitat. It includes everything from continued research, the development of a vaccine against PBFD, the early detection of borer beetles, the management of captive populations, the assessment of logging quotas, as well as the extensive rehabilitation of critical forests.

Conclusion

The vision statement of the aforementioned Action Plan is described as working collectively towards a “thriving population of Cape Parrots acting as a flagship for the protection and recovery of indigenous forests in South Africa, for the shared benefit of people and nature”.

These enigmatic and characterful birds, as South Africa’s only endemic parrot species, are undoubtedly deserving of protection in their own right. However, in reality, the knock-on benefits of protecting the Cape parrot are also of paramount importance, not least of which is the preservation of the country’s few remaining Mistbelt forests and the many species that rely upon them in turn.

Also read:

Finding Africa’s rarest parrots – Cape parrots in Magoebaskloof

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()