A PIONEERING SURVEY OF THE REMOTE RUVUMA RIVER

Like any worthwhile destination, the Ruvuma River does not give up her secrets easily. The journey from Arusha in Tanzania is a three-and-a-half-day commitment by Land Rover, made marginally easier by the stretches of blacktop gradually added to the national road network. First, to Iringa via Singida, Manyoni and Dodoma, then to Songea over the Southern Highlands and through the Makambako Gap, where you geographically enter southern Africa. The stretches of Miombo woodland and riverine vegetation in Ruvuma Region are more akin to the mopane woodlands of Zambia and Zimbabwe, and the further south one drives in Tanzania, the more you feel that this is a different country altogether.

Tanzania feels like a different country the further south one goes

From Songea, following a short meeting with the charming and helpful Regional Administrative Secretary, we continued to Tunduru, a backwater town dominated by artisanal mining of precious and semi-precious stones – soon to be transformed by uranium mining operations in the southern part of nearby Selous Game Reserve. Thanks to heavy rains and deteriorating roads, we only reached the object of our plans and dreams at lunchtime on the fourth day.

At Tungane, the Ruvuma is a broad, lazy stream broken by low rocks and wide sandbanks. On arrival, we set about hauling the canoes, supplies and other equipment off Gian’s trusty Land Rover, affectionately known as “kiboko” – as sturdy as a hippo and equally unwieldy! Once all was packed into the canoes, we waved goodbye to our anxious-looking ground support, who would pick us up at the end, and we paddled off into the afternoon heat.

Unfinished business

Back in September 2000, Marc Baker and I travelled to the Ruvuma to see where the river could be navigated and to obtain a preliminary idea of the conservation and tourism potential of the landscape. It has always been known that the wide expanses of Miombo woodlands between Selous and the Ruvuma River are the wildlife corridor to the equally wild and remote Niassa National Reserve in Northern Mozambique. But little was known about the Ruvuma River and whether it harboured any important populations of flora or fauna.

Aside from fishermen, there is scant record of people on the river

In the 19th Century, Livingstone navigated the river up from the coast, a little past the confluence with the Lugenda River flowing in from the south. In modern times there has been scant record of people on the river besides local fishermen. An internet search yields a couple of accounts by South African teams who have managed to canoe or raft certain sections. Still, nothing systematic has been attempted to cover a defined portion of the river, unsupported by land-based teams, while recording specific data along the way.

Our foray in 2000 did little to add to this scant knowledge. Still, it did emphasise how difficult the Ruvuma River is to access for long stretches and how difficult it was to navigate in an inflatable craft due to the wildly varying nature of the waterways – sometimes broad and shallow, then narrow and rocky, often disappearing into sandy shoals or meandering through mazes of thickly vegetated islands and rocks.

Into the Unknown

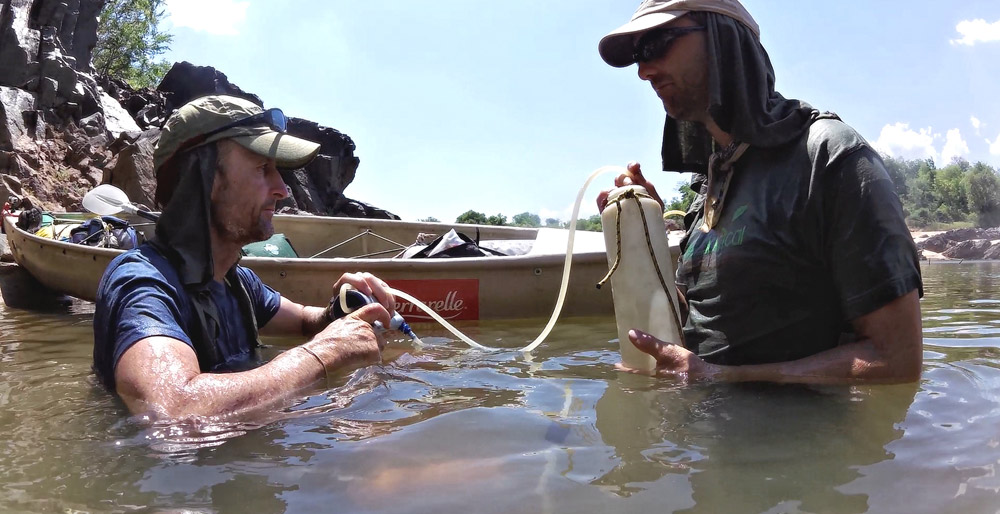

Even in today’s digital world, where the internet answers the most prosaic questions, obtaining facts, figures, and a sense of what to expect during our expedition was not easy. Google Earth offered interesting insights into the varying widths of the Ruvuma and where obstacles such as rapids and islands are. One of our key sponsors, Garmin, provided GPS units that allowed us to “see” ahead to some extent using Basemaps and downloaded datasets. But even the highest resolution images or GPS data could not accurately reveal the depth of water at any one point, the presence or absence of hippos or the seasonal fluctuations in the main flow of the Ruvuma.

Small victories buoyed us while dark storm clouds gathered

Our first day took us a few kilometres downstream, leaving haphazard agricultural areas radiating out from Tungane Village and then entering the Mwambesi Forest Reserve. By evening we had found an exposed sand bar, a feature that would become a regular favourite campsite on our trip. The distinctive tracks of the African clawless otter were found, and we had already recorded two of our target bird species, the rock pratincole and the white-fronted sandplover. While these small victories buoyed us, the dark storm clouds quickening in the west cast a very real cloud over our plans for the next day. If it rained heavily, what would that do to the water levels, and would it make sections of the river ahead impassable?

The grey clouds remained as dawn broke on day two, and a fine drizzle started falling. We decided there was nothing to do but push on, and although the morning was quietly passed, paddling in light rain, by lunch, the skies had cleared, and the sun was out, a state of affairs we enjoyed for the next eight days. By late morning we encountered our first real rapids, an area of rocky cascades and wooded islands that required us to carry and float the canoes through the foaming waterways. Due to our need for eight days worth of supplies and our expectation of long stretches with very shallow water, our canoes were open-topped Canadian “Trapper” style. This meant they were not equipped to ride out areas of water that had the potential to spill over the canoe’s edge. A full load further limited their ability to run white water since they sat low in the water. But our second day proved an excellent testing period as we began to appreciate their performance limits in various water conditions along the Ruvuma.

The Anvil of the Sun

Day three proceeded much as the first two, with some stunning sections of river. Some channels ran between thickly forested islands reminiscent of tropical rainforest and punctuated with the calls of bush shrikes and hornbills. These alternated with open sweeping stretches of river, sometimes close to a kilometre across, flanked by the multi-colour hues of late-season miombo woodland tumbling down to the water’s edge. Cool clear waters mitigated the day’s heat, and our camps on wide sand bars in the river kept us away from the insect-ridden woodlands at night. We observed few large mammals but were thrilled with sightings of some truly special birds: the deep orange-coloured Pel’s fishing owl skulking in the branches of an overhanging tree; the large-eyed, nocturnal white-backed night heron silently fleeing from its perch, and pairs of perky rock pratincoles dancing in flight over the river or boldly standing their ground on their special rock homes as we passed by.

The easy rhythm of these first few days was shattered

The easy rhythm of these first few days was shattered on day four when we came upon the Sunda Rapids, an area of confusing rocky channels, boulders and islands where the river drops a few hundred feet in a short distance. These rapids, clearly visible on Google Earth, herald the beginning of a 12-kilometre section dominated by a sheer rock canyon that cuts its way through a land of giants – enormous granite megaliths soaring into the sky on either side of the river. The canyon, while not deep or very wide, provides few options once inside, and where the channel narrows and the water boils through a six-foot-wide chasm, polishing the basalt to a shining sable blackness, there is no option but to portage to a less hostile section of water.

We repeated this ritual for two days, portaging to avoid the more aggressive parts of this wild canyon, scalding our hands on the black rocks, which we dubbed “The Anvil of the Sun” after T.E. Lawrence’s rocky Arabian desert. We eventually emerged from the mouth of the last rapid into a wonderworld of giant rock outcrops surrounded by oceans of miombo woodlands on both sides of the river. It was unanimously agreed that our campsite that evening on the lip of one of the megaliths, looking west down the meandering river, ranked with the best of our many bush trips. Anyone who loves finding hidden corners of treasured wilderness, out of cell phone range and beyond sight of human settlement or electric light, would recognise why this counted as a genuinely special place. That campsite defined the trip for me, encapsulating what it meant to be on a self-sufficient expedition. After the two physically strenuous days of portaging through the canyon, we slept happily and deeply, lulled into unconsciousness by the barking of yellow baboons and the eery whistling of bush hyrax.

It seemed we were walking and carrying more than we were canoeing

The final few days saw us alternating between easy paddling on slack water and arduous hauling of canoes and equipment over flat rocks and through thick vegetation. Frustration built as it seemed we were walking and carrying more than we were canoeing on the water – the antithesis of a river journey. Additionally, regular encounters with pods of hippos ate up time as we walked our canoes far from the dangerous creatures. As for the highly publicised presence of giant crocodiles in the Ruvuma, either we missed them, or they had moved to another part of the river for, aside from a few smaller specimens, we saw few of these infamous reptiles.

Where The Wild Things Are?

And what, I hear you cry, of all the other wild animals, lurking in the bushveld, ready to eat us? The sad reality throughout the areas that we surveyed is that, while officially designated as wildlife conservation areas of one kind or another, the large mammal populations of these vast woodlands have been steadily reduced through a combination of poorly regulated hunting, illegal bushmeat hunting and poaching. Specifically for elephants, the startling upswing in ivory poaching over the last eight years has drastically reduced populations. In a land where giants once roamed in great numbers, now the only ones of significance are those of immobile granite.

These remote and difficult-to-access habitats are a challenge to patrol against poaching gangs, and lack of direct tourism revenue, or interest, means that they will remain a low priority for a cash-strapped government when compared to the African safari ‘poster-boys’ like Serengeti National Park and Ngorongoro Conservation Area.

Finally, having come to the edge of the Lukwika Game Reserve, we met our long-suffering ground support team. We began our long journey back from the Ruvuma to Arusha, happy to have largely fulfilled our goals but hungry to return to complete other sections of this enigmatic waterway and to bathe in its breathtaking landscapes.

Location & geopolitical significance of the Ruvuma River:

Forms the international border between Tanzania and Mozambique for 650km.

Total length: 760kms.

Basin catchment: 152, 200km2 of which 65% in Mozambique, 34% in Tanzania.

Physical features: Crystalline/sandy soils dominated by Brachystegia/Julbardnnia woodland of the Central Zambesian Biome.

Main protected areas along the length of river: Mozambique – Niassa Game Reserve (and associated hunting blocks); Tanzania – Liparamba Game Reserve; Lukwika-Lumesule Game Reserve; Mwambesi Forest Reserve; Mbangala Forest Reserve.

Wildlife of interest: Historic range of large savannah elephant population, important populations of African wild dog, significant sable antelope populations, African clawless otter, hippopotamus and greater kudu.

Sponsors: Ferarelle; The Italian Association of African Experts; Code 39Films; Garmin; Swarovski Optik.

Contributors

Biologist and conservationist JOHN (JO) ANDERSON moved to East Africa in 1995 shortly after graduating from Oxford University. He has since conducted wildlife research and environmental work throughout East Africa, guided Mount Kilimanjaro climbs more than 50 times, and led specialist travel groups on safaris in Tanzania, and Kenya. Rwanda, Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, Uganda, and Zambia. Jo is a founding partner in Carbon Tanzania, which recently became the first organization in Tanzania to develop a community-led forest-based carbon offset project, working with the hunter-gatherer Hadza people of Northern Tanzania. He lives with his wife and two children in Arusha, Northern Tanzania.

Biologist and conservationist JOHN (JO) ANDERSON moved to East Africa in 1995 shortly after graduating from Oxford University. He has since conducted wildlife research and environmental work throughout East Africa, guided Mount Kilimanjaro climbs more than 50 times, and led specialist travel groups on safaris in Tanzania, and Kenya. Rwanda, Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, Uganda, and Zambia. Jo is a founding partner in Carbon Tanzania, which recently became the first organization in Tanzania to develop a community-led forest-based carbon offset project, working with the hunter-gatherer Hadza people of Northern Tanzania. He lives with his wife and two children in Arusha, Northern Tanzania.

Mammal Specialist ALESSANDRA SORESINA has worked on several wildlife projects around the world. In Saadani Game Reserve in Southern Tanzania, she was involved in a mammal monitoring project which led to Saadani being upgraded to a National Park. In 2001 she set up the lion project in Tarangire National Park, northern Tanzania, and for over 5 years, Alessandra has concentrated her efforts on lion–human interactions. During this time, she has greatly contributed to what is known about lions in and around the Tarangire ecosystem. One of her major goals was implementing the radio-tracking program in Tarangire, allowing conservationists and national park management to understand lion movements in the Tarangire ecosystem fully. After setting up a snow leopard project in the Himalayas with the Università degli Studi di Siena, she is now involved in mammal monitoring projects in Mozambique, Tanzania, Gabon and Botswana which are essential to the implementation of new protected areas.

Mammal Specialist ALESSANDRA SORESINA has worked on several wildlife projects around the world. In Saadani Game Reserve in Southern Tanzania, she was involved in a mammal monitoring project which led to Saadani being upgraded to a National Park. In 2001 she set up the lion project in Tarangire National Park, northern Tanzania, and for over 5 years, Alessandra has concentrated her efforts on lion–human interactions. During this time, she has greatly contributed to what is known about lions in and around the Tarangire ecosystem. One of her major goals was implementing the radio-tracking program in Tarangire, allowing conservationists and national park management to understand lion movements in the Tarangire ecosystem fully. After setting up a snow leopard project in the Himalayas with the Università degli Studi di Siena, she is now involved in mammal monitoring projects in Mozambique, Tanzania, Gabon and Botswana which are essential to the implementation of new protected areas.

Bird Specialist MARC BAKER is the owner and director of Ecological Initiatives Ltd, a Tanzanian company that supports forestry and wildlife conservation in Tanzania. Based in Arusha, Marc has worked in conservation and ecotourism since 1998. Initially, as an ornithologist for the United Nations Development Program – Global Environmental Fund cross-border biodiversity project from 1998 – 2000, conducting a range of biodiversity surveys in Tanzania and Kenya. As a wildlife specialist, Marc works on various ecological issues, such as wildlife management, out-of-protected area tourism viability and carbon forestry for Danida (Danish Development Agency), Care International, the Wildlife Division of Tanzania and the Tanzania bird atlas.

Bird Specialist MARC BAKER is the owner and director of Ecological Initiatives Ltd, a Tanzanian company that supports forestry and wildlife conservation in Tanzania. Based in Arusha, Marc has worked in conservation and ecotourism since 1998. Initially, as an ornithologist for the United Nations Development Program – Global Environmental Fund cross-border biodiversity project from 1998 – 2000, conducting a range of biodiversity surveys in Tanzania and Kenya. As a wildlife specialist, Marc works on various ecological issues, such as wildlife management, out-of-protected area tourism viability and carbon forestry for Danida (Danish Development Agency), Care International, the Wildlife Division of Tanzania and the Tanzania bird atlas.

Adventure sports specialist GIAN SCHAUCHERMANN holds a degree in ecology and fisheries management. Gian has worked on Rubondo Island in Lake Victoria and built bushcamps in Tarangire and Serengeti National Parks. He also spent a great deal of time in the remote areas of Loliondo, where he guided walking safaris and captured some of the finest wild dog photographs. Gian has formal training and certification as a walking safari guide, is a member of the Interpretive Guides Society, and has a pure love of adventure. In his free time, Gian can be found building canoes in his backyard, climbing volcanoes, or adventuring across Tanzania on his motorbike or paramotor.

Adventure sports specialist GIAN SCHAUCHERMANN holds a degree in ecology and fisheries management. Gian has worked on Rubondo Island in Lake Victoria and built bushcamps in Tarangire and Serengeti National Parks. He also spent a great deal of time in the remote areas of Loliondo, where he guided walking safaris and captured some of the finest wild dog photographs. Gian has formal training and certification as a walking safari guide, is a member of the Interpretive Guides Society, and has a pure love of adventure. In his free time, Gian can be found building canoes in his backyard, climbing volcanoes, or adventuring across Tanzania on his motorbike or paramotor.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()