DECODING SCIENCE POST by AG Editorial

The soaring popularity of the social media marketplace has created a global trade where almost anything can be procured over the internet: second-hand car parts, clothing, gadgets and, somehow inevitably, illegal wildlife. Parrots are one of the most trafficked animal orders on the planet and have long been recognised as under siege due to the pet trade. As endangered African grey parrots are removed in their hundreds from the forests of their natural habitats, a new study has highlighted how social media facilitates this trade and how governing bodies, airlines and technology companies can play their part in preventing it.

In a study published in Global Ecology and Conservation, researchers set out to investigate the role of social media in the trade of wild-sourced African grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus and P. timneh) and their conclusions suggest ways in which this method could be used in the fight against illegal trade. While the role of social media in the trade of wild animals has been recognised as a serious conservation concern for years, this study (jointly funded by the World Parrot Trust and World Animal Protection) was the first of its kind to examine the effect on parrots.

The authors of the study examined 259 posts on an unnamed social media site featuring trade in African greys during a period between 2014 and 2018, concluding that over 70% of them contravened CITES regulations. The authors set about analysing every aspect of the posts including the wording and origin of the posts; the ages of the birds (juvenile parrots are recognisable by their grey irises); the behaviour of the birds and the estimated number of birds visible in the included images (often over a hundred birds).

Where possible, they used the images in the posts to obtain information including the Cargo Tracking Code to identify the transit route used and cross-referenced this information against airline records, internal export and import records of the relevant countries and the CITES-published trade reports. In so doing, they were able to confirm which posts featured birds sourced from the wild and that the majority of these trades would have been in contravention of either local law or CITES regulations.

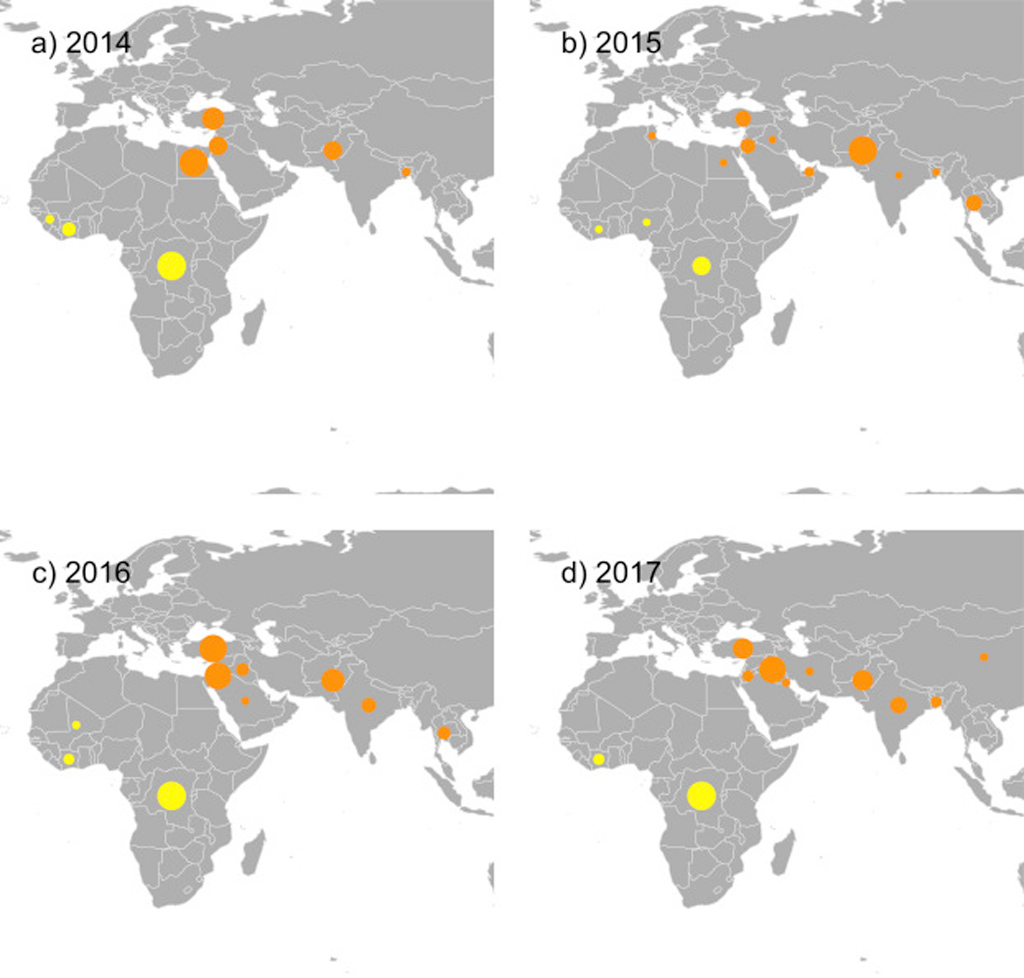

Using this method, the researchers concluded that the vast majority of the exports originated in the Democratic Republic of Congo (a country with a notably poor history of CITES compliance), with a smaller number from west Africa. The parrots were imported predominantly into western and southern Asia (notably Turkey, Pakistan, Jordan and Iraq during the study period) for an average of $203 per bird. Interestingly, in cases where the Cargo Tracking Code could be traced, all shipments of birds were flown by either Turkish Airlines or Ethiopian Airlines and transited through either Istanbul or Addis Ababa. Minimal effort was made to follow standard welfare practices, meaning that the birds were transported in overcrowded crates without perches under extremely stressful conditions.

The study calls upon both technology and social media companies, as well as airlines, to work with experts to take advantage of this newfound intel into trade routes – the former by reporting posts advertising suspected illegal activity as well as removing offending posts and the latter by reporting suspicious shipments to enforcement authorities. This has been made easier since the placement of African grey parrots on Appendix I at the beginning of 2017, meaning that all shipments of wild birds are automatically in contravention of trade regulation.

The Appendix I classification, as well as a suspension on exports from the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2016 (which before that exported around 49% of the wild-sourced African grey parrots), made the time frame for the study particularly relevant in using the data to extrapolate the effect of such regulations.

Interestingly, the study did not find any significant variation in the trade activity across the study period, which the researchers suggest means that the reduced captive market did not increase illegal trade (which is often the contention put forward by those arguing against an Appendix I classification). There was, however, a spike in activity in the months before the enactment to the restriction of trade exported from the DRC which the authors advocate should be taken into account before the adoption of such restrictions or regulations.

The authors emphasise that there are limitations to this method of study, especially given the number of online scams and the inability to access direct private messages, and suggest that their findings present a “snapshot of trade activity”, rather than an accurate reflection of trade. However, this snapshot shows a global market where the traders advertising the sale of these birds do so publicly and seemingly without fear of enforcement.

“Social media has opened up a new front in the ongoing battle against the trapping of wild parrots. While providing new opportunities for traffickers to ply their trade, it also affords valuable insights into how to stop it” said Dr Rowan Martin of the World Parrot Trust and one of the lead authors of the study.

Full report: R. Martin, C Senni and N D’Cruze (2019). Trade in wild-sourced African grey parrots: Insights via social media. Global Ecology and Conservation. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00429

FURTHER READING

• Shades of Grey: https://magazine.africageographic.com/weekly/issue-5/shades-of-grey/

• Get to know the grey parrot: https://magazine.africageographic.com/weekly/issue-5/get-to-know-the-grey-parrot/

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()