- A new continent-wide assessment provides the most accurate picture to date of Africa’s forest elephants. The African Elephant Specialist Group of the IUCN Species Survival Commission produced the report.

- The report improves understanding of this elusive species, enabling stronger conservation planning based on reliable data.

- Updated estimates show 135,690 forest elephants across surveyed areas. This reflects improved DNA-based survey methods – not population recovery, with additional elephants representing previously unsurveyed landscapes.

- Forest elephants remain Critically Endangered, with major threats including poaching, habitat loss, land-use change and fragmented populations, especially in West Africa and parts of Central Africa.

- DNA capture-recapture methods and expanded monitoring have reduced uncertainty in population estimates, revealing previously undetected elephants.

- Despite more precise data, declines continue in key regions, and long-term recovery requires more substantial anti-poaching efforts, improved habitat connectivity and sustained international support to protect these essential forest ecosystem engineers.

A new assessment of African forest elephants provides the most complete and reliable understanding of this species to date. While the updated numbers offer a more accurate picture of forest elephant distribution, and an uptick in previous estimates, they also confirm the species remains Critically Endangered and under high threat from poaching, habitat loss and human pressure.

The report is the most recent African Elephant Status Report (AESR) produced by the African Elephant Specialist Group of the IUCN Species Survival Commission.

First continent-wide survey of forest elephants

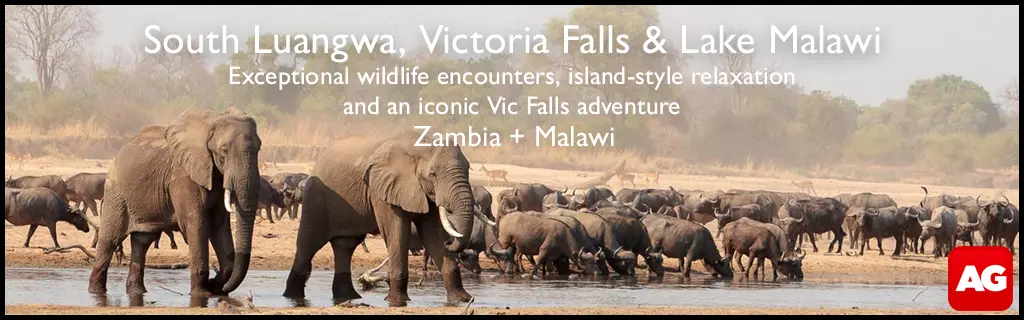

Forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis) are found mainly in Central and West Africa, with small populations in East and Southern Africa. They live in some of the continent’s thickest tropical forests, which makes them difficult to count. Because of this, conservation efforts have previously been held back by gaps in basic information.

The African Forest Elephant Status Report 2024 is the first-ever continent-wide focused solely on forest elephants. It draws from the African Elephant Database (AED), which compiles survey data across 22 range states. This is also the first status report produced since forest and savannah elephants were formally recognised as separate species in 2021.

The result is a clearer understanding of population size, spatial trends and threats. As Yuta Masuda of the Allen Family Philanthropies stated: “Accurate and up-to-date data are critical for understanding the status of African Forest Elephants and strengthening their protection.”

Updated forest elephant numbers: what the data show

According to the report, an estimated 135,690 forest elephants were found in areas surveyed between 2016 and 2024. The 95% confidence interval places the actual number between 99,343 and 172,297, and an additional 7,728 to 10,990 elephants may live in unsurveyed areas.

These figures represent a 16% increase compared to the last assessment in 2016. This does not mean the species is recovering. Instead, improved survey technologies, notably DNA spatial capture–recapture methods, have reduced uncertainty and revealed elephants that were previously missed.

As Prof Rob Slotow, Co–Chair of the African Elephant Specialist Group, clarifies: “The updated numbers of African Forest Elephants should not be interpreted as population growth, but rather as the result of improved survey coverage made possible by DNA–based methods.”

The new numbers reflect better data, not a recovery in population numbers.

Want to see forest elephants in their natural habitats on an African safari? You can see forest elephants in Congo Brazzaville’s Odzala-Kokoua National Park while on safari with Africa Geographic. Or, browse our other African safari ideas here.

Why DNA methods changed the picture of forest elephants

Forest elephants live in dense rainforest where visibility is extremely limited. Standard aerial or ground counts do not work well in these conditions. In the past, most estimates came from dung counts, which required scientists to guess how quickly dung decays. These guesses added uncertainty.

The latest report uses a major improvement in methodology: genetic capture–recapture. By collecting dung samples across large areas and identifying the unique DNA profile of each elephant, researchers can work out how many individuals were sampled and re-sampled. This produces much more accurate population estimates.

This method was used most notably in Gabon’s 2021 national survey, which significantly changed understanding of the country’s forest elephant numbers. Gabon alone now accounts for 66% of the global population. Congo-Brazzaville (the Republic of the Congo) holds 19%, with the remaining animals across 20 other range states.

In addition to Gabon, new surveys in northern Congo-Brazzaville (the Republic of the Congo) and Angola added roughly 600 to 700 elephants to the “new population” category noted in the report.

Overall, 94% of counted forest elephants now come from high–confidence estimates, compared to 53% in 2016.

Where forest elephants remain

Forest elephant distribution is uneven. The updated continental range covers 907,830km², of which 74% has been surveyed. Central Africa remains the species’ stronghold, holding just under 95% of the global population.

Central Africa: Central Africa is home to the most intact tropical forests and the majority of forest elephants. Gabon and Congo-Brazzaville together support 85% of all forest elephants. Here, populations persist mainly in remote forests with strong anti-poaching efforts.

However, major losses continue in some places. The Okapi Wildlife Reserve in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), once an important stronghold, lost about 7 000 elephants when combined with losses in the W–Arly–Pendjari complex in Burkina Faso.

West Africa: West Africa’s population makes up only 5% of forest elephants. Populations are fragmented and isolated due to extensive habitat loss. Forest cover in the Upper Guinean region declined by about 90% between 1900 and 2013.

East and Southern Africa: East and Southern Africa account for less than 1% of the global total. Small populations survive in Uganda, Rwanda, South Sudan and Angola. Many were counted for the first time using updated DNA techniques.

Poaching, habitat loss and conflict

Although poaching rates have declined in some regions since 2018 or 2019, the illegal killing of forest elephants remains high. Forest elephants’ slow reproductive rate, with long gestation periods and long intervals between births, means populations can’t rebound quickly.

Poaching trends vary by region. Central Africa experienced intense poaching from 2003 to 2018. The report recorded 1,080 carcasses at Central African MIKE sites (spots monitored under the CITES Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants Programme) between 2016 and 2024. A total of 730 of these were illegally killed.

In West Africa, weaker monitoring and extensive land–use pressure make trends harder to interpret, but the W–Arly–Pendjari complex shows serious decline.

Habitat loss and fragmentation are expanding threats. Logging, mining, roads, and large–scale agriculture reduce forest cover, create access routes for poachers, and increase human–elephant conflict. Forest elephants often raid crops when habitat is disrupted, leading to retaliatory killings and political pressure.

“We need strengthened anti–poaching measures, better land–use planning for habitat connectivity, and sustained international support to translate the cautious hope provided by this report into long–term recovery,” says Dr Benson Okita–Ouma, Co–Chair of the African Elephant Specialist Group.

Lack of recovery

Forest elephants are important ecological engineers. Their browsing, bark stripping and seed dispersal maintain the structure of Africa’s tropical forests. Some tree species rely almost entirely on forest elephants to disperse large seeds (see, for example, how a decline in Central Africa’s forest elephants has led to a similar decline in ebony trees). A continued decline would alter forest composition and reduce carbon storage.

Despite their importance, forest elephants declined by more than 86% over 31 years up to 2015, driven by poaching and habitat loss. The species’ listing as Critically Endangered reflects this steep decline.

The 2024 report does not show signs of recovery. Instead, it highlights an urgent moment for action. As Dr Grethel Aguilar, IUCN Director General, notes: “This report provides the most accurate picture of elusive African forest elephant populations to date.” A brief moment of clarity, and a warning.

The new assessment offers a sharper, more comprehensive view of a species that has long been difficult to monitor. The numbers are higher not because forest elephants are safer, but because scientists can now count them more accurately. Many populations continue to decline, and major threats remain. But with more accurate data, comes a stronger opportunity to focus conservation efforts where they count.

“With this new data, we have an unprecedented opportunity to focus conservation efforts where they are needed most and give the species a real chance to recover,” says Aguilar.

Further reading

Further reading

- Elephants and ebony: new research reveals how Africa’s forest elephants sustain its darkest wood – and what happens when they vanish

- Forest elephant numbers are believed to have plummeted 86% in just 31 years, yet their role in maintaining forest ecosystems is critical. Read more about these endangered gardeners here.

- Research has uncovered population density declines of 90% for forest elephants and 70% for savannah elephants across Africa in 53 years. Read more about this alarming study here.

- Stunning high-definition camera trap images reveal Nouabalé-Ndoki’s hidden creatures, including golden cat, leopard, forest elephant and palm civet. Check out these portraits of Congo’s ghosts here

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()