The masked bandits of the bushveld

As the sun dips below the horizon, painting the sky in shades of burnished sienna, the cast of the graveyard shift begins to stir. Leaves rustle, feathers are fluffed, lions stretch out sleep-stiffened limbs, and somewhere in the distance, a lone hyena whoops. The creatures of the African night emerge to continue the ceaseless dance of survival. Among them, an African civet pads silently along well-trodden paths in search of its next meal – another furtive ghost of the continent’s mysterious darkness.

The bandits of the bushveld

With their bright, intelligent eyes, sharp features, round ears and black markings, African civets are often described as racoon-like in appearance, but the two species are unrelated. The African civet (Civettictis civetta) belongs to the Viverridae family, along with genets and the lesser-known oyans (also known as linsangs) of West and Central Africa. (Despite its common name, the African palm civet is only very distantly related to African civets and belongs to an entirely different family – the Nandiniidae.) African civets are the sole surviving member of the Civettictis genus, the largest member of the Viverridae family in Africa, and the second-largest civet species after the Asian binturong.

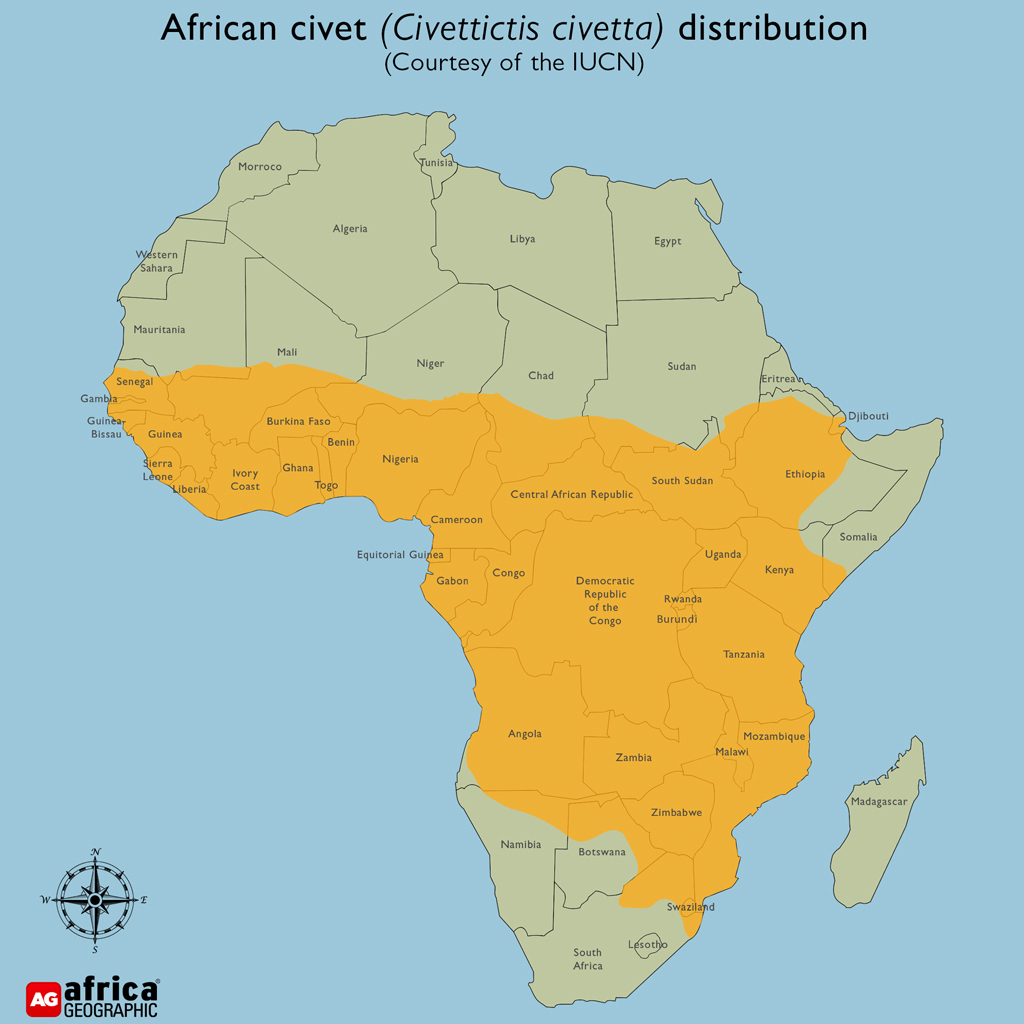

While they occur throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa, these curious animals are primarily nocturnal, occupying favoured hiding places in dense vegetation during the day. As a result, sightings are generally brief unless a lodge happens to have a resident civet that moves through it each night. If the opportunity is presented, close observation reveals that civets are oddly lopsided, with disproportionately large hindquarters. Their thick fur is decorated in unique patterns of spots and blotches that merge into bands running down the legs and tail. Masquerade facial markings and a long crest of fur erected when threatened convey the distinct (and accurate) impression that this is not an animal to be trifled with.

Though generally docile, civets are fierce and agile predators, and when cornered, their defensive growl is surprisingly deep and profoundly intimidating. It is also interspersed with an explosive sound described as “cough-spitting”. The well-developed sagittal crest along the top of the skull and robust zygomatic arch provide strong points of attachment for the temporal and masseter muscles, conferring a powerful bite that belies the animal’s stature.

Quick civet facts

| Height: | 40cm |

| Body length (without tail): | 67-84 cm |

| Mass: | 7-20 kilograms (females smaller than males) |

| Social structure: | Solitary |

| Gestation: | Around 80 days |

| IUCN conservation status: | Least Concern |

Unpalatable preferences

Civets are creatures of habit at night, moving along regular pathways at a slow, tentative walk with heads held low and relying on an acute sense of smell to guide them to their next unsuspecting meal. They have a broad and indiscriminate palate that extends to small mammals, birds and their eggs, invertebrates, fruit and even carrion. However, it is their taste for toxicity that sets civets apart. Millipedes secrete hydrogen cyanide and hydrochloric acid – a noxious combination that deters all but the most determined predators. Though the mechanisms are not fully elucidated, civets can eat and process these toxins, presumably without any discomfort, as millipedes form one of the main components of their diets. They have also been known to casually snack on the fruits of plants belonging to the Strychnos genus, which contain high levels of strychnine.

This gastronomic flexibility allows civets to utilise different resources and thus reduces competition with other medium-sized carnivores.

Ode de civet

The munched millipedes proceed as usual through the digestive tract and are eventually deposited in characteristic civettries. These civet middens are unmistakable, decorated as they are with the white exoskeletons of invertebrate prey (and the sheer size of the droppings, which almost defy the physical limits of anatomy). The trees beside civettries and along popular paths are marked with a pungent pale-yellow secretion from large perineal glands known as civetone. Civets essentially live through their noses and have been known to be driven to a rubbing and marking frenzy by strong-smelling objects. Things like rotten fruits attract their attention, and they “neck-slide” against the offending stink, repeatedly smearing their contribution of civetone along the way. Even unsuspecting pangolins have found themselves victims of this scent-induced delirium.

Civetone may be putrid smelling when concentrated, but diluted formulations create a pleasant scent. For this reason, civetone has been included as a base in perfumes for hundreds of years. While today, most commercial perfume companies have replaced civetone with synthetic ambretone, the practice persists, and boutique scents made from civetone remain popular. Most of this natural civetone is sourced from caged male civets in Ethiopia, caught in the wild and kept under appalling conditions.

While, unlike their Asian cousins, African civets have escaped the bizarre tradition of making coffee from beans in their faeces, they are believed to be extensively hunted for bushmeat in parts of Africa. Though the impact has not been thoroughly studied, experts believe that thousands of civets are killed every year in the forests of Nigeria and Cameroon, which could well be contributing to local population declines.

The solitary civet

Left to their own devices, civets are solitary, though little is known about the extent of their social dynamics or sex territoriality. A female in oestrus will call to prospective mates with a sound described as a “moaning meow” by biologist Richard Estes. Some 80 days after her amorous songs are answered, she will seek a suitable den site and give birth to between one and four kittens.

Civet kittens are born well-developed compared to other carnivores and are walking within a few days and exploring outside the den at around three weeks old. Adorably, they display what is known as clustering behaviour, where if one gives out a contact call, its siblings will immediately move to join it. They are weaned quickly, eating solid food from about a month old and reaching independence as early as four months.

Find a civet in the wild

Civets favour savannah and forest habitats and are absent from the more arid areas of Botswana, Namibia and South Africa. Though widely distributed, their nocturnal and elusive habits make encountering one in the wild a rare treat. In southern Africa, the dry and cold winter months offer the best chance of a sighting, as the civets are more likely to move at dusk.

Given Africa’s profusion of charismatic animals, it is perhaps inevitable that some of the smaller, more obscure species might be overlooked in all the excitement of a safari. Yet the Africa civet is one of the continent’s unique offerings – a silent phantom that stalks the African night.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()