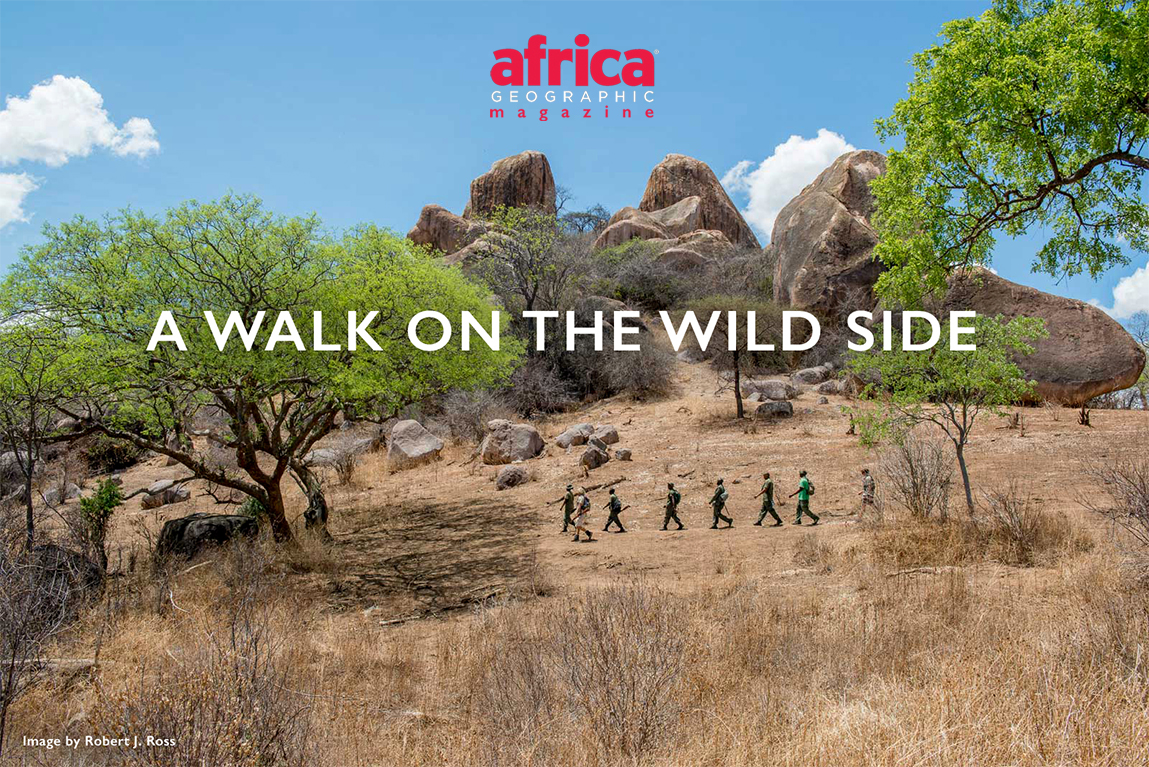

RANGER TRAINING IN RUAHA EVOKES THE PERIL AND BEAUTY OF WALKING SAFARIS

A middle-aged elephant bull stands in the Ruaha riverbed – towering over five younger bulls that follow him around. It’s a spot on the Mwagusi sand river where the underlying rocks push water toward the surface, making it easier for the elephants to dig. The wind has died, and a little ash shaken from an old sock drifts slowly to the ground. The elephant moves his foreleg back and forth, shovelling sand away, creating a hole big enough for his trunk to siphon up the cool, sand-filtered water.

One of the younger bulls does the same, his ears waving in a desperate attempt to keep cool in the oppressive heat. The others rest, huddled together as if trying to hide their faces, their ends of trunk relaxed and flat on the ground. A Tamarind tree provides little shade when its leaves are leafless. Every move is deliberate.

The dry season screams for rain until the soil is hoarse and inflamed

I click my fingers softly to get the attention of the six rangers hunkered down with me behind some rocks. Simon Peterson, a fellow guide, whispers some questions to them: Where is the wind coming from? Are we close enough? Do the elephants pose a threat? Could we be in a better position? Do we have an escape route? Where are the elephants most likely to go should they become alarmed? The leading ranger shakes his ash bag again. The wind is erratic because of the stifling heat that sends swirling thermals up the river, but we judge we’re in a safe place. We watch the elephants a little longer, then retreat.

Ruaha National Park in Tanzania gets under your skin. It’s intense. Magical. Extreme. The dry season screams for rain until the soil is hoarse and inflamed, only to make way for thunderstorms that turn gullies into violent torrents, and grasslands into moving sheets of water. Those who come to Ruaha usually visit during the dry season, when the watering holes in the surrounding hills dry up, and the wildlife is forced down to the Great Ruaha River. Huge herds of buffalo move between massive lion pride territories, creating scenes fit for sensational documentaries.

It’s common to see greater kudu, bushbuck, impala and dik-dik feeding on dark red flowers dropped by yellow baboons sitting high up in the kigelias. Giraffes maintain the browse lines on these sausage trees and, if you look closely, you may notice that one of the eponymous sausages hanging down is, in fact, a leopard’s tail. In more remote areas, roan, sable, and hartebeest come to drink from less lion-infested springs. But, as those who have seen the seasons change in Ruaha know, its wildness encompasses more than big game. There are more than 1,600 plant species, and the bird list exceeds 600, with at least three endemics. Ruaha is also a place of elephants.

But the elephants were so hammered by poaching in the 1970s and 80s that most of the big tuskers have been killed, effectively selecting for genetically small or absent tusks. But even these surviving tuskless matriarchs and their progeny are not immune to the recent surge in poaching. Despite all this, Ruaha boasts the largest elephant population in Tanzania at present – but only because the Selous population was decimated by even more intense poaching.

We were here teaching a six-week-long walking safari course for government rangers. Our team consisted of a doctor, a former professional hunter with years of experience in firearms training, and four guides with experience leading walking safaris in Ruaha and other wilderness areas.

The training was part of a larger project funded by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) called ‘Strengthening Protected Areas Network in Southern Tanzania’ (SPANEST). Walking safaris in Ruaha had been severely impacted by a series of tragic accidents in preceding years. The reactions of authorities and safari operators to these incidents tended to be impulsive rather than analytical, so something absolutely had to be done to improve safety. Through the vision of Godwell Meing’ataki (Project Coordinator) and Paul Harrison (Technical Advisor to UNDP), funds from the SPANEST project were allocated specifically for walking safari guide training.

By walking you become a participant rather than a mere observer

In Tanzania, rangers are government employees whose primary job is protecting wildlife from poaching, and who only occasionally protect tourists on walks led by professional guides. Their training is limited to law enforcement, and most ambitious new guides set their sights on sitting behind the wheel, shuttling tourists around places like Ngorongoro and the Serengeti. So it is no surprise that the walking safari industry is underdeveloped.

Safe walking safaris offer the opportunity to focus on the subtler aspects of nature that are difficult to appreciate from a vehicle. Instead of listening to an engine, you hear your own footsteps, and might even realise how loud your breathing is. It’s easier to smell the wild herbs and feel the bark’s textures. You make way for a Sungusungu ant colony coming down an elephant path, and you realise how relative scales of time and distance are. You become a participant rather than an observer. The baboon bark or impala snort is aimed at you as the super-predator, not the leopard or lion. A vulnerability becomes apparent, sharpening your senses. It is also incredibly peaceful.

Our course started with five days of first aid training focusing on identifying, managing and preventing medical emergencies in the wilderness. The American definition of “back-country” or “wilderness” for the purpose of emergency medicine is anywhere further than twenty minutes from definitive care. The southern parks in Tanzania are at least six hours from definitive care, even with an efficient evacuation plan. So, action rather than reaction is the mantra of the course. Recognising and preventing medical issues is also critical in preventing accidents. For example, participants learned to recognise signs of dehydration because it can lead to irrational behaviour or the inability to follow instructions at a critical moment, thereby posing a safety risk.

The most dangerous animal is a human with a gun

Walking in the vicinity of dangerous animals, particularly elephants, buffalos and lions, is inherently risky, so firearms training is an important aspect of the course. There is much truth in the statement that the most dangerous animal in the bush is a human with a gun, so the training is focused on ensuring safe, accurate and professional handling of the heavy calibre rifles.

In the extremely rare case that a potentially dangerous animal actually becomes dangerous, decisions must be made quickly. There is no margin for error when an animal is moving toward you with intent. The high-calibre rifles necessary to stop elephants and buffalo fire one shot at a time and carry only a few rounds in the magazine. Firing a second bullet requires manually operating a bolt to eject the spent cartridge and re-chambering the second round. So the first shot is critical.

Some of the more difficult and subtle training involves attitudes and awareness of natural history. There is a disproportionate fear of some potentially dangerous wildlife, stemming from cultural stigmas and false information. One example is the fear of snakes. I grew up in a village, and like most Tanzanian children, we were taught to be terrified of snakes.

Any snake sighting incited hysteria, and people running to kill it with hoes and machetes. Elders would embellish stories of black mambas moving so fast that they seemed to be flying. It wasn’t until I was much older that I met people who handled snakes. Through study, I learned to understand that not all snakes are dangerous and that even dangerous snakes usually try to avoid people. Exploring misconceptions about the potentially dangerous game needed our careful consideration. The reason we use the term “potentially dangerous game” is that, under normal circumstances, they aren’t dangerous. We armed rangers with the knowledge and experience to guide crucial decision-making.

If you don’t have some fear you don’t understand the risk

It’s a struggle for some of the rangers to reconcile their long-held fears. If your perception of elephants is built on the same sentiments as my previous fear of snakes, sitting on a ridge watching elephant feeding below, or climbing onto boulders to safely let a herd come past, can be terrifying. We spent a lot of time discussing the fact that fear is healthy because it makes you careful. If you don’t have some fear, you don’t understand the risk, and this makes you dangerous.

Jane, a single mother with a young son, offers a good example of overcoming fear safely. The first woman to receive an Interpretive Guides Society Walking Certificate, she was initially hesitant to walk in areas with elephants, and the .458 rifle was heavy for her at first. But she has got used to it and, following her training, she is now better able to understand elephant behaviour, and so protect her guests, herself and her son.

Andrew Molinaro (Moli), who leads private walking safaris in Ruaha, has noticed changes in the rangers. ‘From our first course in January 2013, the difference in attitude and competency of the rangers has been extraordinary. They are now well-versed in the concepts and procedures of a bushwalk. Rangers understand the animals much better now and have far more confidence in themselves. They now form an integral part of any walking safari.’

There’s a long way to go. This kind of training is expensive and requires a good deal of time, but it’s a start. Pietro Luraschi, a specialist walking guide and co-trainer, pointed out, ‘You can see the pride of being part of an elite team of qualified walking guides.’ These are important steps, as the neglected southern circuit of Tanzania continues to seek recognition as the world-class wildlife and wilderness destination that it is.

As we return to the vehicle from the elephant sighting, we stop under one of Ruaha’s iconic baobab trees. Brown parrots screech as they fly away, white petals of the baobab blossoms float to the ground where impala, kudu and bushbuck will feed. It’s an opportunity to talk about pollination and baobab ecology.

We feel the mud-caked marks where elephants have rubbed their hide, and we inspect the damage where they’ve ripped bark from the tree. In the bark of another baobab, we find the end of a tusk embedded. One side of the tree is covered with hundreds of small holes, a few of which bear wooden pegs, evidence of human honey gathering. Some of the peg marks are recent – honey poachers, as they are now called – but some scars date back 500 or 1,000 years. How old is a baobab tree, really?

This is one of the issues we discuss. Are all these baobabs a similar age because they were able to flourish when there were enough people here that elephants stayed away? As we discuss the history of humans in the park, we notice an old grinding stone, then some pottery shards. High up in the branches, two male scarlet-chested sunbirds bicker, then a greater honeyguide arrives and starts chattering at us. He wants us to follow him to honey and leave him some beeswax and grubs in thanks. The evidence of our reliance on, and once-integral role in, the ecosystem becomes increasingly apparent. By walking in the wild, we are reminded of who we are.

Contributor

ETHAN KINSEYwas born and raised close to Arusha, where he and his wife now make their home. Being outside, immersed in nature, has always been a part of his life, from catching tadpoles and birding as a child to winter sports during college vacations. More recently, it has taken the form of sharing wildlife and wilderness experiences with guests, specialised guiding, guide-training, and personal learning ventures. Primarily engaged in designing and guiding private safaris throughout East Africa, he is also active in developing guiding standards through the Interpretive Guides Society.

ETHAN KINSEYwas born and raised close to Arusha, where he and his wife now make their home. Being outside, immersed in nature, has always been a part of his life, from catching tadpoles and birding as a child to winter sports during college vacations. More recently, it has taken the form of sharing wildlife and wilderness experiences with guests, specialised guiding, guide-training, and personal learning ventures. Primarily engaged in designing and guiding private safaris throughout East Africa, he is also active in developing guiding standards through the Interpretive Guides Society.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()