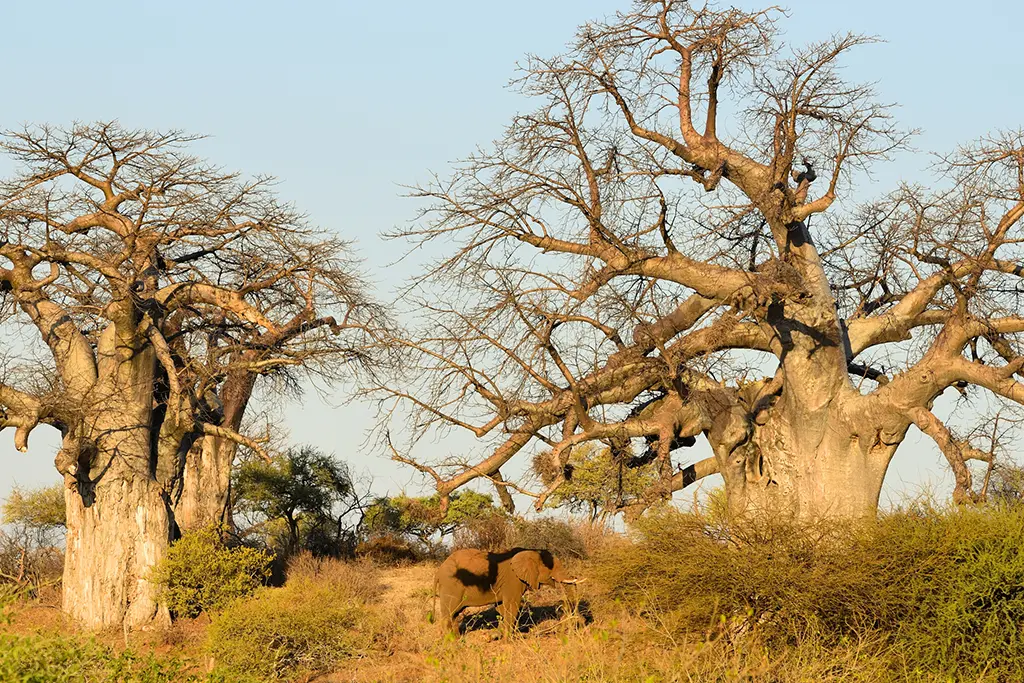

Managing elephants in South Africa’s protected areas is one of conservation’s most persistent dilemmas. Elephants are a keystone species that shape ecosystems – opening landscapes, dispersing seeds, and maintaining biodiversity. But some studies identify elephants as the main drivers of large-tree loss in African savannahs, especially when their populations go unchecked. A new study on Kruger elephants explores how the opinions and strategies of managers, landowners, and tourists differ on managing elephant impacts, from culling to contraception and protecting large trees.

In the reserves of the Associated Private Nature Reserves (APNR), which form part of the Greater Kruger ecosystem and share an open boundary with Kruger National Park, elephant numbers have increased sharply – from about 500 in 1993 to between 2,000 and 3,000 today. At the same time, large trees have declined, especially in areas dense with artificial waterholes. This trend has created concern among reserve managers, landowners, and tourism operators, all of whom depend on a balance between elephants, vegetation, and visitor experience.

A study published in the European Journal of Wildlife Research by Cook, Witkowski, and Henley (2025) explores how the insights and opinions of conservation managers, landowners, tourists, and guides differ on elephant management – from culling and contraception to closing waterholes. It reveals a clash of ethics, economics, and ecology that shapes how Africa balances its giants and trees – and challenges one-size-fits-all conservation thinking.

The legacy of Kruger elephants

Between 1967 and 1994, more than 14,000 elephants were culled in Kruger National Park to maintain a population “carrying capacity”. That policy ended under international pressure, allowing numbers to increase rapidly to more than 30,000 today.

The removal of fences between Kruger and the APNR in 1993 allowed elephants to roam freely into the private reserves. However, because these reserves maintain a much higher density of artificial waterholes than Kruger – roughly 2.5 per km² versus Kruger’s 0.1 per km² – elephants spend more time concentrated in smaller areas. The result: persistent browsing and bark-stripping that kill large, old trees, some of which are crucial for nesting birds, shade, and tourism value. However, elephant feeding is not purely destructive. By dispersing seeds in their dung and opening up dense vegetation, elephants promote plant diversity and maintain grassland habitats. Still, because elephants favour certain tree species and sizes, sustained browsing can remove specific tree types or height classes from an area, affecting other species that depend on large trees for nesting.

This situation, often called “the elephant problem,” forces managers to weigh ecological science against ethical and economic considerations.

The study

Researchers surveyed 170 stakeholders in the APNR – including conservation managers, property owners, tourism staff, and visitors – to gauge support for four strategies to reduce elephant impacts on trees: waterhole closures, to disperse elephants naturally; tree protection, such as wire-netting or beehive deterrents; contraception, to limit population growth, and culling, to reduce numbers directly.

Respondents rated these approaches using a five-point scale and were invited to comment on their reasoning. The analysis examined how age, experience, gender, and stakeholder role influenced views on each option.

Shared concern, divided solutions

Almost all respondents agreed that elephants and large trees are both valuable. 97% said elephants contribute to tourism, and 96% supported protecting large trees on both ecological and aesthetic grounds.

However, while most acknowledged that elephants damage trees, fewer believed there are “too many elephants.” Many saw tree loss as a natural ecological process rather than a crisis. This tension – between recognising ecological impact and resisting population control – runs throughout the study.

Managing Kruger elephants: what people support

Waterhole closure received the strongest support overall (59%), especially among younger conservation managers, who viewed it as a natural and ecologically sound approach. They argued that reducing artificial water availability would restore seasonal movement patterns and relieve localised pressure on trees.

Tourism operators were less convinced, worrying that closing waterholes could reduce wildlife sightings and, by extension, visitor satisfaction. The economic risk of “fewer elephants to see” weighed heavily against perceived ecological benefits.

Tree protection methods, such as wire-netting or beehives, were popular with property owners and tourists (77% support). They were seen as practical and non-lethal, as they protect iconic trees while maintaining tourism appeal. But respondents also commented on limitations: these methods are labour-intensive, costly, and unrealistic at scale. Participants observed that “it’s not realistic to protect every tree this way”. This highlights the gap between local success and landscape-wide impact.

Contraception divided opinion sharply (43% support). Tourists were generally in favour, seeing it as humane and consistent with modern conservation ethics. Long-term stakeholders, particularly older landowners and conservation managers, were more sceptical. They questioned whether large-scale contraceptive programmes are feasible in the wild, citing cost, logistics, and uncertainty about social effects on elephant herds.

Culling was the most contentious option. Just over half of respondents (51%) agreed it would reduce tree damage, but culling also brought strong ethical opposition. This was especially true among tourists. Older respondents in the study were more likely to support culling, recalling its past effectiveness. Conservation managers viewed it as a pragmatic, if undesirable, tool for population control. Others rejected it outright as incompatible with modern conservation values and harmful to South Africa’s tourism image.

Are you keen to see the elephants of South Africa’s Greater Kruger? Check out these amazing safari ideas to Greater Kruger.

Are you keen to see the elephants of South Africa’s Greater Kruger? Check out these amazing safari ideas to Greater Kruger.

What influences opinions

The study found clear demographic divides. Age and experience mattered. For example, those over 50, who had lived through the culling era, were more supportive of lethal control. Younger respondents preferred adaptive, non-lethal management – reflecting a shift towards “compassionate conservation,” which emphasises welfare as well as ecology.

Gender also played a role in stakeholder opinions: men were more likely to support culling than women. Tourism stakeholders tended to prioritise visitor experience, while conservation managers focused on ecological function.

The study showed many conservation managers were in favour of waterhole closures. Property owners favoured non-lethal options like tree protection and contraception. Tourists clustered almost entirely around non-lethal preferences.

A values-based approach to managing Kruger elephants

The study concludes that there is no single “correct” strategy for managing elephants and trees. Instead, management should be adaptive and values-based – combining scientific monitoring with social acceptability.

While ecological data can identify when intervention is needed (for example, when tree loss exceeds thresholds), stakeholder values determine which interventions are socially sustainable. In the APNR, this might mean a mix of localised tree protection, selective waterhole management, and population control through contraception, with lethal measures considered only as a last resort.

The study also highlights the importance of communication and education. Misunderstandings about the feasibility of contraception, or the ecological outcomes of waterhole closures, suggest a need for ongoing dialogue between managers, landowners, and visitors.

The broader lesson

Elephant management is often portrayed as a technical problem, but this research shows it is equally a social one. Decisions about waterholes, contraception, or culling are shaped by ethics, economics, and experience as much as by ecology.

By documenting these perspectives, the authors provide a framework for balancing scientific objectives with human values – a critical step in ensuring long-term coexistence between elephants, large trees, and the people invested in both.

Reference

Cook, R.M., Witkowski, E.T.F., & Henley, M.D. (2025). “Stakeholder values on the management of African elephants for large tree conservation in protected areas.” European Journal of Wildlife Research, 71:104

Further reading

- Research says Kruger’s elephant numbers have been underestimated, with improved aerial surveys revealing a growing population of elephants

- Research shows that wire-netting can be used to significantly increase tree survival by reducing elephant impact on large trees. Check out the study on this net win here

- Discover the surprising link between carbon markets & elephants: how protecting Africa’s miombo woodlands benefits both climate & wildlife

- Elephants feeding on fan palm trees are preventing the palms from reaching full size & reproductive potential in Kruger NP, says a study

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()