Courageous tusked pigs of Africa

For some reason, history has marked the warthog as an object of lampoonery. From the happy-go-lucky Pumba to being listed as one of Africa’s “Ugly 5”, warthogs always seem somewhat unfairly caricatured. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with a bit of humour on safari (and they certainly won’t be in the slightest bit bothered), but it is well worth remembering that there is always more to wild animals than meets the eye.

For a start, warthogs are fast, hardy and courageous. And a bit of time spent observing their antics will reveal a wealth of personality and attitude beneath that rather homely façade.

Which warthog?

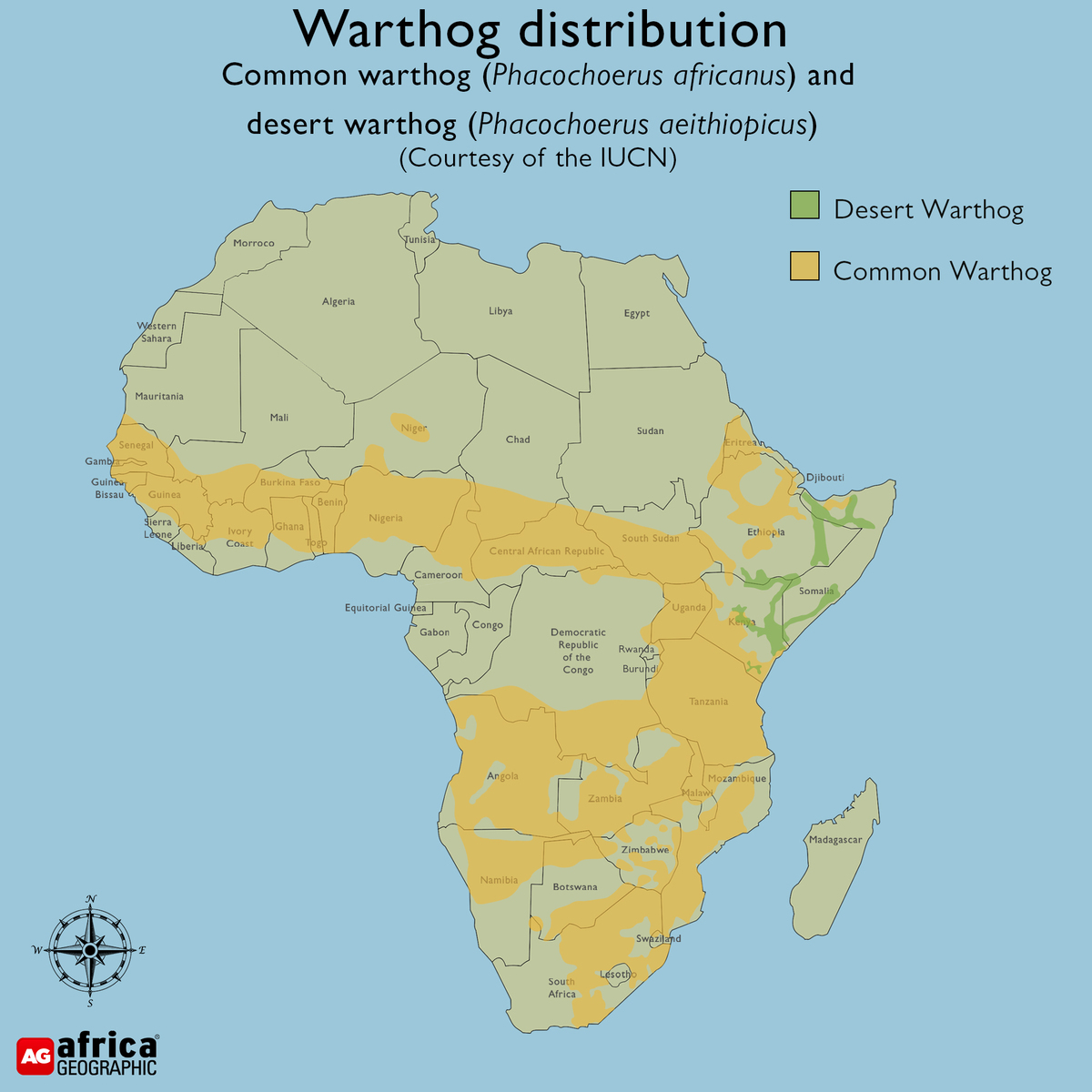

Unbeknownst to most, there are two species of warthogs roaming the African continent – the common warthog (Phacochoerus africanus) and the desert warthog (Phacochoerus aeithiopicus). As the name implies, the former is the more widely distributed of the two and is found throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa. The desert warthog is restricted to the Horn of Africa, extending from south-eastern Ethiopia through Somalia and central Kenya. They can be distinguished from their common cousins by a complete absence of incisor teeth. Neither species survives well in forest habitats.

The desert warthog was a surprise to researchers of the early 2000s. Until then, the species P. aeithiopicus was known to science but believed to have gone extinct in South Africa during the late 19th century. The warthogs of the Horn of Africa were thought to be a variant of P. africanus. However, morphological and genetic analysis revealed the desert warthogs to be the surviving members of P. aethiopicus.

Apart from minor morphological differences, the two species share most physical and behavioural features. They are both heavy-headed members of the Suid (pig) family, with modified canine teeth extending out of their mouths as tusks. Each warthog has two sets of tusks: the upper maxillary pair that in males may grow over 25cm in length and the shorter but razor-sharp mandibular pair. Like the tusks of elephants, these continue to grow throughout the warthog’s life. Though not as valuable as elephants’ ivory, warthog ivory is carved and traded.

The conical facial protuberances for which warthogs are named are outgrowths of thickened skin believed to serve a defensive purpose. Those of mature boars are particularly well-developed, and the suborbital pair below their eyes can protrude as much as 15cm, conferring a somewhat alien shape to their faces. Scent glands are positioned at the base of each tusk and corner of the eyes that both sexes use to mark sleeping and feeding areas and waterholes. (This rubbing behaviour is often wrongly interpreted as scratching.)To complete the oil-painting that is the warthog, the grey, wrinkled skin is covered by a sparse layer of bristly fur, and they appear almost bald but for the ridge of mane that runs down the centre of their backs. The absurdly skinny tail ends in a tuft of bristles and is held upright when the animal is alarmed or fleeing. Warthogs have minimal subcutaneous fat and this, combined with a thin covering of hair, makes them vulnerable to extreme temperatures, particularly cold. They will huddle together below ground to stay warm at night and often only emerge several hours after sunrise on cool, cloudy days.

Quick facts

| Height: | 63.5-85cm |

| Mass: | Males: 60-150kg |

| Females: 45-70kg | |

| Social structure: | Sounders |

| Gestation: | Around 170 days (roughly six months) |

| IUCN conservation status: | Least Concern |

Knuckle-walkers

Warthogs are primarily grazers and spend most of the morning and late afternoon foraging. This they do with rump raised skyward, resting on roughened pads on their carpal (wrist) joints. Warthogs exhibit omnivorous tendencies and will supplement their diets with insects, eggs and even carrion – they have even been known to chase cheetahs off kills to grab a bite or two. They are prolific diggers, especially during the dry season, when they survive predominantly on bulbs, rhizomes, and roots. Like other pig family members, their snouts are well-adapted for digging and rooting, with an extra prenasal bone serving as a support and attachment for muscles and ligaments. The top of the nasal disc is also hardened and shovel-like.

Warthogs are strictly diurnal and retreat to a network of burrows before the fall of darkness. They can dig out their own tunnels but often opt for the more efficient approach of renovating abandoned aardvark networks. Interestingly, these are often shared with nocturnal porcupines as differing diel cycles make the two species ideally suited bedfellows. These burrows also serve as boltholes for warthogs that have attracted the attention of one of their many predators.\

Sound(er) and fury

Though not strictly territorial, warthogs generally remain within a home range throughout their lives and have an intimate knowledge of the terrain. If attacked, their first defence is always to flee, and their turn of speed is simply astonishing. Not only are they capable of attaining speeds of close to 50km/hour, but their acceleration would shame some of the fanciest car models. They aim for the nearest burrow and disappear bottom first, with razor-sharp tusks facing front and centre to deter the more determined pursuers.

If the warthog fails to find refuge, it will fight fiercely to defend itself or its piglets. Though hyenas, wild dogs (painted wolves), leopards and lions are all potential predators, many do not walk away from such hunts unscathed. Though the top tusks are more for show than anything else, the bottom pair continually rubs against the upper, creating a razor edge easily capable of slicing through skin.

As a side note, many a novice guide or tracker has got the fright of their career when foolishly walking in front of a seemingly innocuous hole in the ground without giving it a suitable berth. The experience of 100-odd kilograms of pig flying past your legs at light speed is not soon forgotten and is at best, a learning experience, and at worst, may evoke the need for a few reconstructive surgeries and extensive physiotherapy.

This little piggy…

Warthog boars also use their tusks during the rut at the start of the dry season. Forehead to forehead, these dramatic fights can last for hours as competitors thrust and parry, often leaving both parties bloodied and exhausted. The fruits of their labours (so to speak) arrive with the next season’s rains, as tiny piglets begin to emerge from below ground on wobbly legs.

Beauty may well be in the eye of the beholder regarding adult warthogs, but their piglets are undeniably heart-meltingly winsome. Females can give birth to litters of up to eight piglets at a time, so they are almost ludicrously tiny during their first forays into the wide world. The sows live together in sounders – most likely consisting of related females – and will care for and suckle each other’s piglets. The vulnerable youngsters very quickly grow a line of white fur along the bottom of their cheeks, presumably to mimic tusks as nature’s way of making them seem less edible.

Unfortunately, it has no deterrent effect, and warthog piglets are preyed upon by everything from the larger predators to eagles and snakes. Less than half will survive their first year, despite the mother’s brave and fierce attempts to defend them. Surviving females stay with their mothers in their natal groups, but subadult males eventually wander off and form bachelor groups with other youngsters. It will likely be several years before they are large enough to compete for mating rights.

Final thoughts

Almost any safari is all but guaranteed to yield at least one sighting of a warthog. Chances are there will be a sounder or two that spends the day in and around your lodge. So it makes sense to fully appreciate them not just based on their rather haggard looks but for the fascinating creatures they are – warts and all.

Resources

Read all the facts you need to know about warthogs here.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()