Journey into the red zone: Kingsley Holgate's Afrika Odyssey expedition

People often ask us what the most important item is to have on an expedition. The expected answer is usually things like a well-stocked medical kit, fuel jerry cans, 4×4 recovery equipment, the basics (Nando’s sauce, Mrs Balls chutney, marmite), extra spare tyres, a big camp kettle and a bottle or two of your favourite plonk. But they’re a wee bit surprised when we give our answer. Over the years, one of the most important things we’ve found is, wherever possible, to have an empty seat so you can load up a local character who’s got the language, knows the culture and can bring your journey alive with homegrown knowledge and contacts.

After back-tracking from Ennedi in northern Chad to the busy Kousseri border with Cameroon and facing a daunting route into Nigeria to reach Benin, we load up a confident young fellow by the name of Barka Abani – a cross-border trader who knows the badlands and backroads of this region well. What a bonus Barka turns out to be: he easily handles the tricky paperwork of remote border crossings, and guides us along rutted sand tracks pockmarked with deep washaways and fuel smugglers in overloaded, swaying trucks going flat-out. He takes to camping wild in deserted quarries like an old-timer, and is a wizard at negotiating our way through countless military roadblocks in the volatile north-eastern territories of Nigeria.

Further south, Nigeria’s traffic is mindboggling: tuk-tuks and motorbikes weaving in and out at crazy speeds with not a crash helmet in sight, crabbing busses and trucks with names like ‘God Rules’, ‘Triumphant Child’, ‘God Knows Better’ and ‘Masha Allah’ coming at you on the wrong side of the road, and speedsters with a death wish. Some days later, a smiling policeman drops the rope at the last roadblock, shouting, “White man – how are you? God bless Nigeria!” One must admire the Nigerians’ good humour and zest for life.

Renowned African explorer Kingsley Holgate and his expedition team from the Kingsley Holgate Foundation recently set off on the Afrika Odyssey expedition – an 18-month journey through 12 African countries to connect 22 national parks managed by African Parks. The expedition’s journey of purpose is to raise awareness about conservation, highlight the importance of national parks and the work done by African Parks, and provide support to local communities. Follow the journey: see stories and more info from the Afrika Odyssey expedition here.

Amazons, slaves, voodoo and insurgency

At African Parks Benin HQ in Cotonou on the Atlantic coast, we receive a hearty welcome from regional manager Hugues Akpona and his team; it seems they’ve been looking forward to the expedition’s arrival for days and are relieved we’ve made it from Chad in one piece.

Benin is laid-back and calm after the energetic chaos of crossing Nigeria. It has an extraordinary history dating back to the 11th century, including a vast empire known for its gold, ivory and trading savvy; the sophisticated but now lost medieval city of Edo that had earthworks longer than the Great Wall of China; the world’s only all-female army – so ruthless that European colonists called them ‘Amazons’ after the merciless warrior-women of Greek mythology; and the exquisitely crafted Benin Bronzes – sculptures that date back to the 1500s.

We first explored this small, fascinating West African country some 15 years ago as part of a Land Rover journey to track the entire outline of Africa through 33 countries in 449 days. In our book from that expedition, ‘Dispatches from the Outside Edge’, we told the story of Benin’s voodoo king endorsing that expedition’s Scroll of Peace and Goodwill, the eerie Sacred Forest at Kpasse with its voodoo god statues, the ancient Python Temple and the heartbreaking sight of the Door of No Return on the beach at Ouidah, which stands at the place where a million slaves clad in chains were sent into the shallows to board slaving ships, to be carried away forever across the Atlantic to the Caribbean and Americas.

Now we’re back again with a different objective: to reach Pendjari and W National Parks, numbers 20 and 21 of this conservation, community and culture-themed Afrika Odyssey Expedition. But after more than a year of zigzagging across the continent to connect all 22 African Parks-managed protected areas, we’re starting to feel the pace. The grub boxes are near-empty, our clothes are stiff with dried sweat and dirt, we’re down a couple of belt notches, and everything is coated in thick dust.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari lodges and campsites where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? You can view and book accommodation to various African Parks destinations by clicking here.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari lodges and campsites where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? You can view and book accommodation to various African Parks destinations by clicking here.

Still, the expedition Defender 130s gamely grind on, now with 60,000 kilometres on the clock and redolent with that typical expedition smell of unwashed socks, over-ripe bananas and pungent curry powder from a spilt bottle somewhere. Graeme Madsen, who joined the team in Chad, says they’re the best he’s ever driven; he can’t believe their capabilities.

Into the ‘red zone’ en route to Pendjari

To complete this penultimate chapter, we must travel to the far north of Benin to reach the last strongholds of West Africa’s most endangered wildlife. However, there are plenty of travel warnings about jihadist threats spilling over from neighbouring Burkina Faso, which is, according to some security advisories, now high on the global terrorism index. Pendjari and Park W are currently off-limits to tourists. Still, Jaques Kougbadi, African Parks’ energetic head of communications for Benin, who’s travelling in the lead Defender as our interpreter, guide and cameraman, assures us that all will be OK.

We take a deep breath and tackle the long road north. Jacques arranges for us to overnight at a small, homely lodge called Le Bélier in the town of Natitingou, where Sammy Kassim, the friendly owner, tells us he is risking all in the belief that tourism to Benin’s national parks will soon return. “This place used to be full,” he says sadly, waving a hand across his empty restaurant whilst praising the conservation and community work being done by African Parks. “Now, the government and the military will secure the area; we have hope.”

Early the following morning, under the watchful eye of six well-armed military vehicles, we’re told to keep close – no more than four metres apart – as we push on in intense heat and dust through the thickly wooded country, following the base of the Atacora Mountains. Much to our surprise, a motorbike procession suddenly appears and, with loud chanting and singing, joins the convoy to lead us to the opening of a community water point constructed by African Parks.

Hundreds of colourfully dressed villagers are milling around the new solar pump borehole, storage tanks, livestock water troughs and a long line of taps for domestic drinking water. There’s frenetic drum beating, dancing, joyful singing and congratulatory speeches. At that moment, the seriousness of our military protection is forgotten as we join the celebrations. It’s also a reminder of how important it is for conservation to work with neighbouring communities, even in difficult and sometimes dangerous circumstances like these.

Pendjari

Back in the convoy, we reach the main gate of Pendjari National Park. Jacques explains we’re the first visitors in many months following an IED attack in 2022 that tragically killed a group of African Parks personnel, one of whom we knew. More recently, some villagers were brutally beheaded.

A small team of armed rangers on motorbikes ride slowly ahead of the expedition Defenders, carefully scanning the road and verges for any sign of IEDs that might have been recently planted. “It’s standard procedure; we grade the roads regularly to make it easier to identify human tracks and activities,” Jacques tells us. Our cheerful radio chatter fades to silence as the magnitude of what the park’s staff face daily hits home.

At Pendjari’s HQ, we meet the instantly likeable park manager Habte Tadesse – tough, stocky and full of fun. Over small cups of Ethiopian coffee, 42-year-old Habte tells us that he grew up in southern Ethiopia, where his father and grandfather had both been game rangers in the Omo National Park and learned his English at the South African Wildlife College.

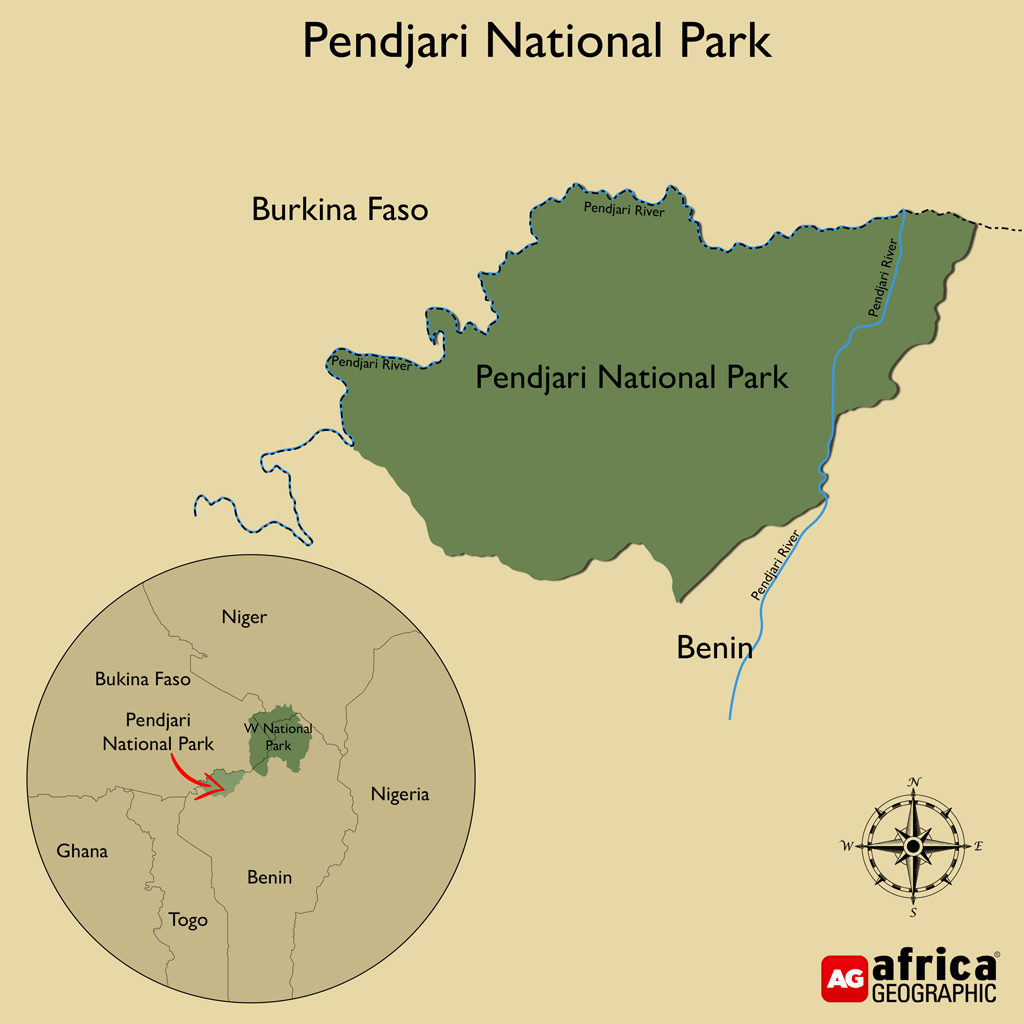

Sitting up on a hill in an open-sided rondavel that serves as a canteen with forever views, Habte explains that both Pendjari and W National Parks form part of the 26,361-square-kilometre transnational W-Arly-Pendjari complex that spans Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. It’s the largest intact ecosystem remaining in West Africa and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

“This is the last refuge for the region’s elephants – we’ve recently collared a number of them – and some of the remaining critically endangered West African lion population, not to mention the korrigum antelope (looks like a topi) and the western hartebeest – species that you’ve probably not seen before,” explains Habte.

“We must continue to protect and safeguard this area, not just for the wildlife but also for the people,” he continues. “The government of Benin is 100% supportive; they even help fund the conservation work in both parks, which with other important partners, helps us to keep our promises to the communities. We can win this war against the jihadists; theirs is a fight for ideology – ours is for conservation and communities. If the north falls to jihadists, it will be the beginning of the end for Benin, and the government knows that. That’s why we have such commitment with more than 3,000 soldiers deployed along the border. Their job is to protect; ours is to conserve for the future.”

The sky goes dark. Pendjari’s camp cook is a genius, producing the best crispy chips and sunny-side-up, soft-fried eggs we’ve had in months. That night, we resort to sleeping under wet sarongs to get some relief from the unrelenting heat and humidity. The following day, after the coffee ceremony with Habte (three or four small cups each Ethiopian-style), we explore the Park HQ; the infrastructure is impressive: graded roads, airstrip and hangers, neatly thatched accommodation units, offices, ranger quarters, a training centre and a state-of-the-art boma including a strong-walled quarantine pen – “For when the black rhinos arrive,” says Habte with a grin. “Everything you see is built by local labour,” he adds proudly.

After a night sleeping out under the stars at the Mare Bai waterhole, with an alert ranger team standing guard and Habte adding water to the expedition’s symbolic calabash, we fly by helicopter over Pendjari, spotting lots of wildlife and, in the distance, a military camp close to the border with Burkina Faso.

Later, at a flag-raising ceremony in the parade ground with the ranger corps, Habte thanks us for the immense journey we’ve undertaken to reach Pendjari despite it being in a ‘red zone’ and for assisting with their community work: Rite to Sight-reading glasses for the poor-sighted, malaria prevention for mums and children and the Wildlife Art competition for schoolkids at Pendjari’s environmental clubs.

“Our appreciation for your monumental effort to visit Pendjari is shown in the many messages from rangers, staff and government officials that have now been added to your Scroll of Hope for Conservation…what a great book for the future!” he exclaims.

Park W

Bidding the Pendjari team farewell, we turn the expedition Defenders towards Park W, so named for the w-shaped meanderings that the Niger River has carved in this border region. It’s a winding road that takes us through the lands of the Batammariba or Tata people; animists who, surrounded by ancient baobabs, live in tall, conical, thatched and mud-built fortified village complexes called ‘sombas’. They resemble miniature castles built on different levels with beautiful granaries and entrances protected by fetishes and shared by both people and livestock.

But Kingsley isn’t doing well. He’s been battling to shake off a nasty bout of malaria that surfaced as the expedition left Chad. Despite two courses of malaria treatment, the heat and unrelenting expedition pace have taken their toll. Arriving at Park W, he’s swaying on his feet like a big baobab about to crash. Still, he insists on participating in the energetic, traditional dance welcome ceremony, meeting the local Chief and Abdel-Aziz, the very professional park manager, who hustles our team into a waiting helicopter with well-armed protection on board, to fly to the centre of Park W.

At a beautiful river setting, Abdel-Aziz adds water to the symbolic expedition calabash, which has collected thimblefuls of water from all African Parks-managed areas across Africa. This is ceremony number 21 – the last but one of this Afrika Odyssey Expedition.

Picking up the story in Kingsley’s words:

“Back at base camp, we’re surrounded by elephants, who’ve come down at sunset to drink from the beautiful natural pools. These are some of the last remaining elephant herds in West Africa. Abdel-Aziz comes over to me, where I’m sitting alone, touches me on the shoulder and says quietly, ‘These elephants are safe here. Thank you for coming to Park W and allowing us to share them with you.’ Despite feeling as sick as a dog, this moment makes it all worthwhile. But next morning, I wake to see Ross, Abdel-Aziz and Dr Samuel Mvuyekure (the AP camp doctor) gathered around my bed and discussing ‘The Patient’. Last night hadn’t gone well: my heart rate was all over the place, and I struggled to breathe; Dr Samuel had to put me on oxygen.”

“I’ve radioed for the plane – we’re medevac’ing you to hospital. When it lands, the pilot isn’t going to cut the engine,” Abdel-Aziz tells Kingsley. “Dad, I’m not taking no for an answer,” says Ross firmly. Twenty minutes later, Kingsley is bundled into the front seat of AP’s Cessna 206, with the smaller Dr Samuel squeezed into the back and on a three-hour flight south to a busy government hospital in Cotonou.

Dr Samuel finds the last available bed for Kingsley and, refusing to leave his side, sleeps on the floor using Kingsley’s well-travelled, 20-year-old Melvill & Moon bag as a pillow and a Maasai shuka as a blanket. Dr Sam is from Bujumbura in Burundi and served with AMISON, the peace-keeping force in Somalia, where he had his fair share of challenging medical situations. What a good man. He is another example of the committed, quality characters that African Parks attracts, and he is very determined to ensure that the ‘Beard’ in his care isn’t going to breathe his last in Benin.

“The Beninese people are wonderfully kind and friendly,” says Kingsley in a ragged voice note a couple of days later. “They excelled themselves; a constant stream of doctors and nurses (I think curiosity was a driving factor), chest x-rays, every blood test, drip, painkiller and antibiotic imaginable. It got me breathing properly again; it seems it could be a double-whammy of complicated malaria and a pneumonia-type thing. Frightening experience, but I’m on the mend!”

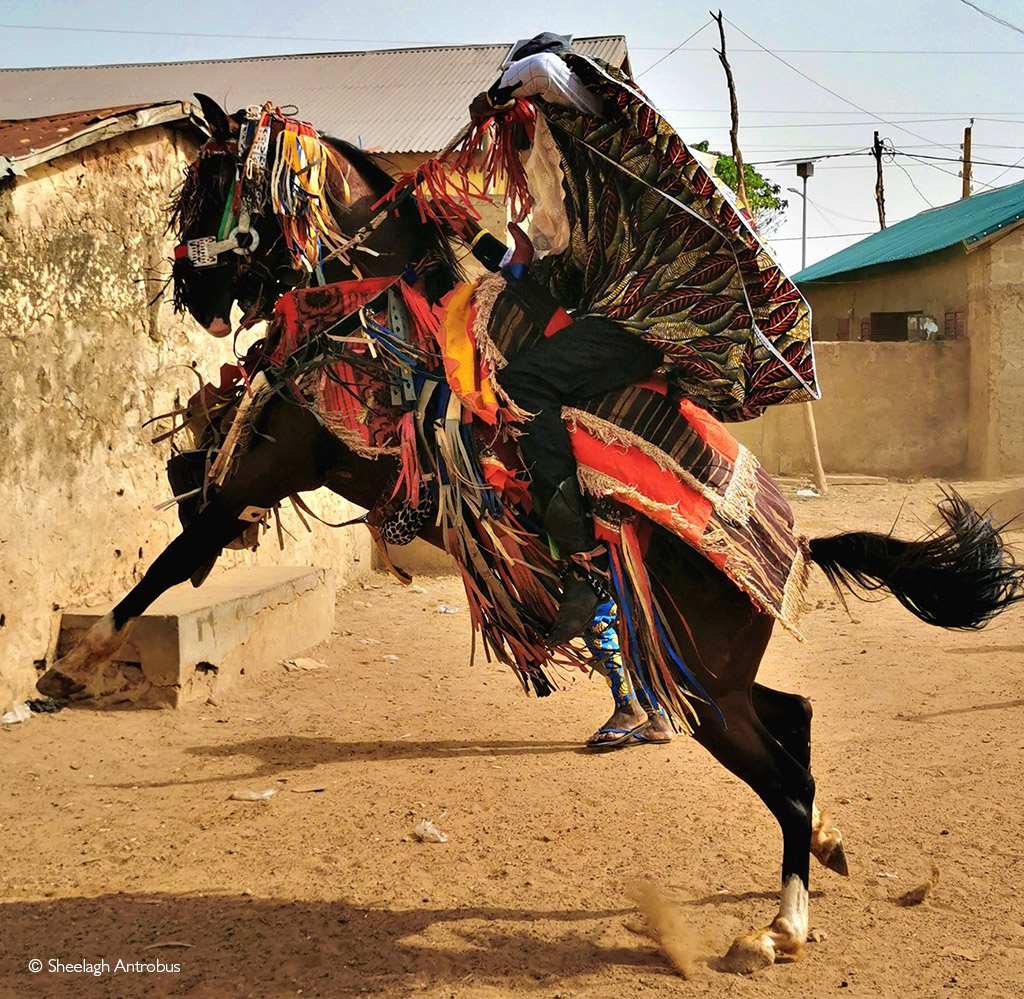

Meanwhile, the expedition team are in a race against time to complete the community work at Park W. Jacques whisks Ross and Graeme off to meet the celebrated Bariba Horsemen of the Banikoara Commune. “Their equestrian skills are incredible,” reports Ross. “The colourfully dressed horsemen on their richly harnessed mounts put on a great show to the accompaniment of sacred drums and blaring, hand-crafted two-metre-long trumpets. With great dignity, they also wrote messages in the Scroll to show their support for the conservation and community work being done in this border region.”

Constantly aware that we’re in a high-risk security area, the humanitarian work is conducted at an intense pace: malaria prevention with women, Rite to Sight for the elderly and Park W’s Wildlife Art competition for community kids; their joy at being singled out for their efforts is priceless to watch.

Our time in Benin’s northern national parks ends with a sobering event. With Abdul-Azziz and park rangers, we line up on either side of a simple, stone memorial for a moving ceremony to remember those who’ve died in the line of duty here, many of them from cross-border insurgent attacks.

Pendjari and Park W are the last conservation strongholds in this part of West Africa. More than 50 large mammal species rely on these two African Parks-managed areas for their continued existence, including elephant, buffalo, a dozen antelope species, hippo, spotted and striped hyena, leopard and the critically endangered West African lion and Northwest African cheetah.

Threats to their survival aren’t just from insurgents; habitat destruction from overgrazing, illegal hunting and fishing are just as severe as the pressure from cotton cultivation, Benin’s largest cash crop. But what a great conservation and community job the African Parks team does under these challenging circumstances; their resilience, passion and commitment make us proud to share their stories – well done, African Parks, for refusing to give up.

And so, we point the travelled-hardened Defenders back south to Cotonou and meet a cheerful but few-kilograms-lighter Kingsley. Over a few cold La Béninoise (Benin’s national beer), we discuss the final challenge: to reach Chinko in the eastern region of the Central African Republic, surely the most remote wildlife reserve in Africa and the very last of the 22 African Parks-managed areas we must visit to successfully complete the mission of this Afrika Odyssey Expedition. We can smell victory – but it’s not over yet.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()