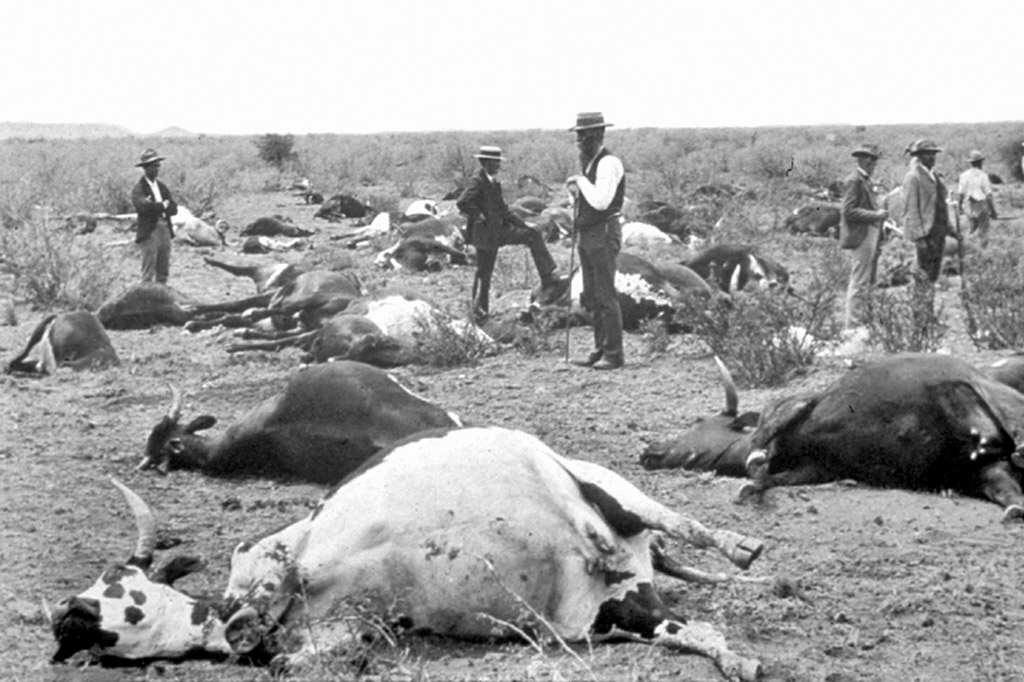

In June 2019, The Pirbright Institute in Surrey destroyed the most extensive laboratory stock of rinderpest virus remaining in the world. With the disease officially declared eradicated in 2011 and a digital record made of the genetic code, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and World Organization for Animal Health had begun to put pressure on labs around the world to reduce risks of accidental release. The rinderpest outbreak of the late 19th century was one of the most devastating plagues in African history – it killed 90% of Southern and East Africa’s cattle and the subsequent starvation killed as many people as the Black Death. It wiped out a third of Ethiopia’s population. Its effect on the continent’s wildlife was equally extreme, and the ramifications are still felt well into the 21st century.

The virus

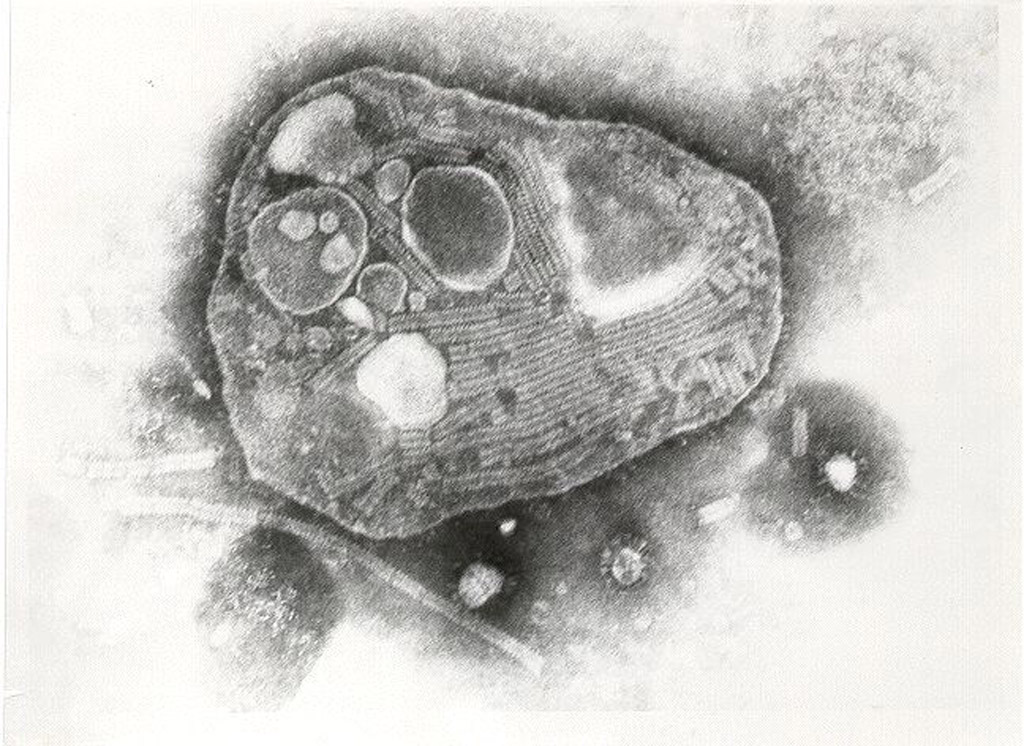

The virus that caused rinderpest was a member of the genus Morbillivirus, which also includes the measles and canine distemper viruses. Humans are unaffected by rinderpest, but measles evolved from rinderpest somewhere around the 11th century, allowing it to make the zoonotic jump to human beings. Like all viruses, the rinderpest was incapable of reproducing without a host – proteins on the surface of the virus’s surface allowed it to bind to receptors on the host cell membrane before fusing with the cell and emptying its genetic contents into the cytoplasm. From there, the virus essentially hijacked the cellular processes of the host to replicate before the newly created virions would bud off the cell membrane and infect the next set of cells. Though the virus initially targeted the lymphatic and respiratory systems, virions were present in all bodily fluids, making it easily transmittable.

The disease progressed rapidly and caused ulcerating sores in the soft tissues of the affected animals, along with a multitude of other symptoms including extreme fevers, loss of appetite, diarrhoea, and weakness, usually resulting in death after around ten days. While the name “rinderpest” means “cattle plague”, it was highly contagious and not specific to cattle – it jumped to wildlife species including giraffe, buffalo, warthog, and antelope such as kudu and wildebeest. It had a fatality rate of up to 100% for previously unexposed animals, meaning that it decimated vulnerable populations of wild animals.

The virulence of the virus, short incubation period and rapid progression of symptoms made it extremely difficult to control. After it was introduced to the Horn of Africa around 1887, it moved southwards leaving devastation in its wake, before reaching Southern Africa in 1896. Efforts to control the virus eventually eradicated it in Southern Africa in 1905, though other parts of Africa were less fortunate.

Vaccines

It was known that any animal that survived a rinderpest infection was immune for the rest of its life. There was also anecdotal evidence of farmers using the bile of infected animals to attempt to inoculate other animals, which carried risks of actually causing an infection. Naturally, the enormous economic, animal and human costs of rinderpest outbreaks ensured that a great deal of attention was devoted to developing a vaccine around the globe. Though there were several breakthroughs in developing vaccinations, it was Walter Plowright who is credited with developing the tissue culture vaccine in 1962 (based on similar techniques used to create the polio vaccine) that conferred lifelong immunity and was cheap and easy to produce.

A major outbreak in the 1980s originating in Sudan spread throughout Africa and, once again, killed not only livestock but local wildlife as well. This led to the African Rinderpest Campaign, which gradually rid most of Africa of the disease through a combination of vaccination programmes and close monitoring of outbreaks. In 2011 the Food and Agriculture Organization declared rinderpest officially eradicated. As such, rinderpest joined smallpox as the only infectious diseases to have been successfully eliminated.

Africa’s wildlife and the Serengeti trophic cascade

The cost of rinderpest virus outbreaks in Africa to human lives was staggering and largely incalculable. In some parts of Africa, the way of life for certain tribes and people that survived was irrevocably altered. With the scope of this human tragedy in mind, it is easy to see why the effect that it had on wildlife is often under-represented in discussions around the history of rinderpest. Yet some populations of wild animals remain under threat today at least partly due to its effects, especially those affected by the 1993-1997 outbreak in East Africa. That particular outbreak decimated populations of buffalo and eland, and the population of the lesser kudus (Tragelaphus imberbis) in Tsavo National Park in Kenya was believed to have declined over 60%. Roan antelope were also particularly susceptible to its effects. While many animal species face several threats, including habitat loss and poaching, rinderpest had a devastating impact on already struggling populations.

As is now well know, if not well understood, imbalances in natural ecosystems can have completely unforeseeable consequences and diseases play their own role in this effect. White-bearded wildebeest of East Africa were particularly hard hit by the virus and by the middle of the 20th century, the migratory wildebeest in the Serengeti-Maasai Mara ecosystem numbered under 300,000. However, from the mid-1970s, as Plowright’s vaccination research eradicated rinderpest in the area, the wildebeest population exploded to reach today’s equilibrium of around 1,5 million animals. This, in turn, led to what researchers describe as a “trophic” cascade, essentially: more wildebeest ate more grass which left less fuel for fire which increased the number of trees and mediated the balance between woody and grass plant cover. Pathogens like rinderpest with the capacity to devastate wild animal populations do more than only affect the animals that catch them – they can change the face of an entire ecosystem.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()