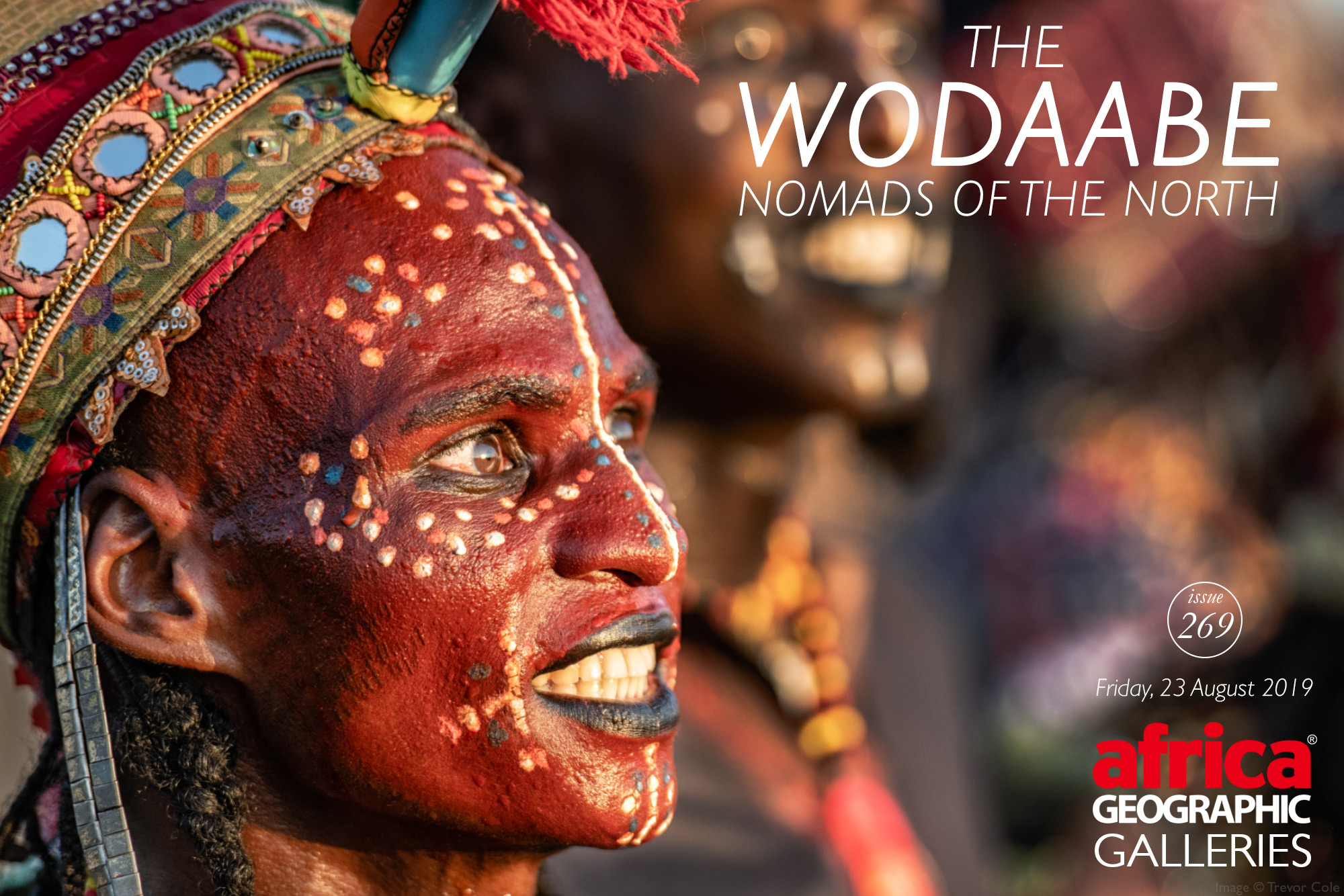

Where beauty reigns supreme among the 'people of the taboo'

The Wodaabe tribe are nomadic pastoralists of the Sahel region in Africa. Their migratory journeys cover the expanse of northern Africa, where they travel with their cattle and families across the arid areas of Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad and the Central African Republic. They are a small, isolated branch of the Fulani ethnic group and are considered by neighbouring tribes as wild, uncivilised people, labelled as Mbororo, or ‘cattle Fulani’ – those who dwell in cattle camps.

They speak Fula, but do not read or write the language. In Fula, Woodabe means “people of the taboo”. The code of ethics (pulaaku) of the Wodaabe emphasises reserve and semteende (modesty), munyal (patience and fortitude), hakkilo (care and forethought), and amana (loyalty).

The Wodaabe place great emphasis on beauty and charm as this plays a vital role in their culture. When it comes to establishing relationships, the responsibility falls to the man who is required to attract the attention of a woman. Because of this, men will invest large amounts of time, money, and effort into beautifying themselves.

Once a year these nomads come together in a festival known as the Gerewol. It is the most important ceremony among the Wodaabe where men compete to be selected by young marriageable women as the most beautiful. I went to Chad for a week to watch the Gerewol festival, the location of which is not decided upon until the last minute. Still, it is always held at the end of the rainy season in the Sahelian zone which has seasonal rainfall and grass that provides grazing for the cattle.

![]()

In this beauty pageant for the men, the women are usually younger (in some cases they may be as young as 12 or 13), and the men are seen as fair game in a society which is polygamous and polygynous. The male beauty ideal of the Wodaabe stresses tallness, white eyes and teeth; the men will often roll their eyes and show their teeth to emphasise these characteristics.

The men adorn themselves using an array of colourful face paints. Their outfits are also vibrantly decorated, embellished with beads, feathers, buttons and baubles in the brightest of colours. Mirrored tunics and hats add to the exuberance and adornment. The overall appearance with the paint, makeup and outfits can only be described as feminine from our cultural perspective. They dance like male peacocks or birds of paradise, which exhibit their plumage to attract females. They are animists at heart, and this may be why they emulate the animal kingdom.

At this festival, there were two groups of Wodaabe: the Sudosukai and Japta. They both use scarification on their faces and bodies, using razor blades and ash, which is then rubbed into the open wound. The result is a black tattoo which is slightly keloidal (raised).

This scarification starts when they are young children, and tattoos are added with time. The Japto are more heavily scarred than the Sudosukai. There are perhaps some physiological differences too, with the Sudosukai being finer – many have model-like features, and all are very slim.

They dance endlessly at this festival, keeping to their ancient rhythms which are repeated over and over. When it gets too hot, they take breaks, but on the last night, they will dance continuously until dawn. The dancers often drink a fermented bark concoction which provides them with the energy they need to dance for long periods. This ‘energy’ drink reputedly has a hallucinogenic effect.

The dances are the focal point of the festival, with the main dance spectacle being the Yaake. Here the men line up and put on their best show, while three women – who are specially chosen as judges by the male tribal elders based on their fortitude and patience – pick the most attractive male.

To participate in the Gerewol, the women must have menstruated before the festival. Effectively when choices are made, the women know they are going to have sex with the chosen Wodaabe male, if the male accepts them. This may be a one-night affair or may last for longer, sometimes culminating in marriage.

Men may have a few wives, with the second or third wife regarded in good stead by the first wife. If a husband is infertile, he may ask a fellow tribesman to impregnate his wife, and in some cases, men will allow their wives to have sex with more handsome men so they can have more handsome children. Children are seen as a sign of machismo, wealth and labour, and having many children helps to offset the high infant and child mortality rate.

Cattle also indicate wealth; they very rarely eat them. Instead, they are predominantly vegetarian and consume millet, milk and occasionally cassava or manioc. They do, however, trade the cattle for other goods. Their animal husbandry is superb, and I witnessed boys as young as seven in charge of tending to the herd. The children grow up quickly in such a society. They have no formal education, and their culture is still resilient to an encroaching outside world.

As a tribe, they perform the Gerewol for themselves and not for any visitors. From what I know, not many tourists have witnessed the festival in Chad, whereas more have seen it in Niger, although instability has curbed potential tourism opportunities. There were only a few photographers and travellers when I was there, but the friendliness of the tribe was universal – although quite a few were shy, which is part of their cultural code. I hope that tourism to this region and these cultural festivals remains sustainable.![]()

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, Trevor Cole

Born in the City of Derry (Ireland), Trevor Cole has lived most of his life outside the bounds of Ireland; in England, Singapore, Togo, Italy, Ethiopia and Brazil. He returned to Ireland (Donegal) in 2012. His photography, and travel, have become two of Trevor’s life’s passions. His photography focuses predominantly on culture and landscapes; images which reflect a spatial and temporal journey through life and which try to convey a need to live in a more sustainable world. He seeks the moment and the light in whatever context he finds himself and endeavours to use his photographic acumen to turn the ordinary into the extraordinary.

He leads small photo tours in his ‘own Donegal’ and Ireland but also to other destinations. He lived in Ethiopia from 2006-2010 and since then has returned to take photographers to the Western and Eastern Omo, Harar, the Danakil desert and the highlands of Ethiopia. Additionally, he takes photo tours to Iceland, Namibia and India and travels on his own to discover and capture new locations – often with a focus on indigenous people.

He has been published by National Geographic (online), several British and European digital photography magazines and newspapers and the Survival International calendar in 2016.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()