Trophy hunting is one of the most polarising topics in conservation. Supporters argue that, when properly regulated, hunting can generate funding for wildlife reserves, support anti-poaching efforts, and contribute to habitat preservation. Opponents say it threatens biodiversity, disrupts ecosystems, and undermines non-consumptive tourism models. But where does the truth lie? Is trophy hunting a necessary evil, a beneficial conservation tool, or an outdated practice needing reform? To explore this debate, we turn to Timbavati Private Nature Reserve (TPNR), a key component of the Greater Kruger ecosystem in South Africa.

Trophy hunting is one of the most polarising topics in conservation. Supporters argue that, when properly regulated, hunting can generate funding for wildlife reserves, support anti-poaching efforts, and contribute to habitat preservation. Opponents say it threatens biodiversity, disrupts ecosystems, and undermines non-consumptive tourism models. But where does the truth lie? Is trophy hunting a necessary evil, a beneficial conservation tool, or an outdated practice needing reform? To explore this debate, we turn to Timbavati Private Nature Reserve (TPNR), a key component of the Greater Kruger ecosystem in South Africa.

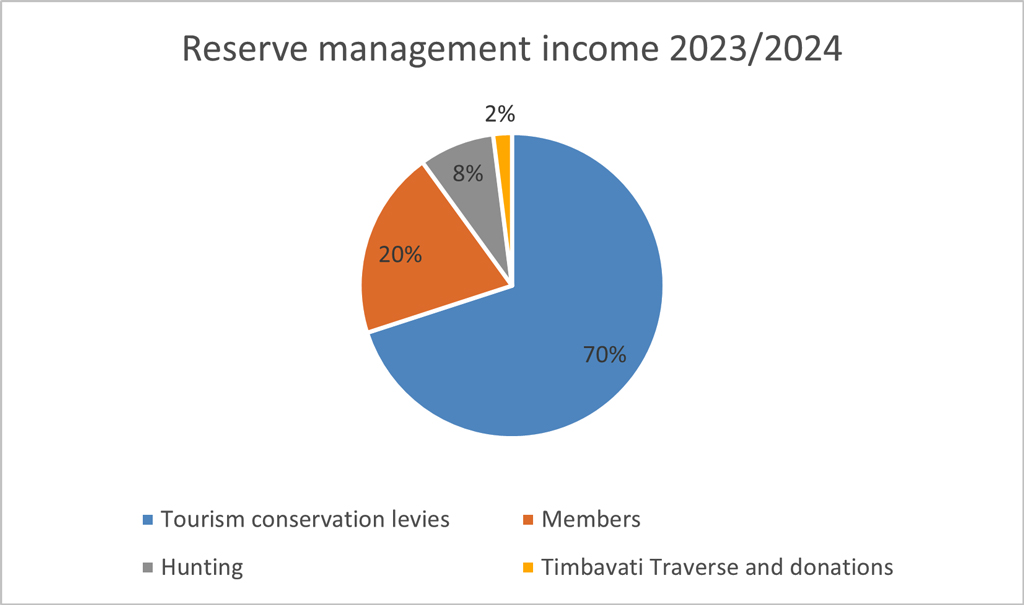

Unlike state-protected areas, Timbavati receives no government funding. The reserve relies on a mixed funding model that includes photographic tourism and regulated hunting. Africa Geographic has been engaging with Timbavati management to ask difficult questions about its trophy hunting policies and offtakes. Timbavati, in response, has supplied detailed information on their hunting offtakes and feedback on their current policies and philosophies.

In the case of Timbavati, it is essential to position this debate within the broader context of the Greater Kruger ecosystem, which operates as an interconnected social-ecological system. The discussion around hunting is not merely about ethics, but about balancing conservation, community needs, economic stability, and sustainable land use.

A crucial contextual note is that TPNR is distinct from the lodges in the reserve. Timbavati consists of privately owned properties whose owners have agreed to collaborate by removing fences to allow wildlife to roam freely. Some landowners operate lodges on their land subject to Timbavati regulations. Other landowners have no lodges on their land, and some have leased their land to third parties to build and manage lodges – again, subject to Timbavati regulations. The landowners pay levies to TPNR, and lodges pay Timbavati fees for every tourist visiting the reserve. The TPNR is responsible for managing the reserve in accordance with Kruger National Park regulations (as it forms part of the Greater Kruger open system), maintaining infrastructure and preventing poaching (their most significant cost). Landowner levies, tourism bed-night fees and trophy hunting fund Timbavati.

Timbavati offers a valuable case study for assessing whether trophy hunting can be a viable tool for long-term conservation. In this article, we analyse Timbavati’s financial model, hunting quotas, and ecological impact for the 2023/2024 period – and ask the ultimate question: is the reserve’s approach to hunting sustainable, or should conservation funding be secured through alternative means?

The role of trophy hunting in Timbavati’s revenue model

Timbavati faces the ongoing challenge of securing sustainable funding for conservation. Unlike national parks, Timbavati doesn’t receive any government contribution and must generate its own revenue to finance operations. The reserve relies on two main funding streams: photographic tourism and trophy hunting. While photographic tourism contributes most of Timbavati’s budget, and Timbavati is a popular Big-5 safari destination, trophy hunting has historically been a financially significant – yet controversial – element of the reserve’s financial model.

“The Greater Kruger area is a mosaic of values held by diverse stakeholders, including private landowners, local communities, conservation authorities, and tourism operators,” says Edwin Pierce, warden of Timbavati. “These stakeholders hold different perspectives on wildlife management and land use. TPNR’s model reflects this diversity, maintaining a balanced approach between photographic tourism and regulated hunting. Many landowners within the reserve express valid concerns about over-reliance on tourism revenue, fearing that it could lead to over-tourism issues similar to those observed in East Africa. Trophy hunting, when carefully regulated, thus serves as a complementary economic activity that mitigates economic vulnerability and the risks associated with tourism saturation.”

Within one year between 2023 and 2024, photographic tourism contributed over 70% of the reserve’s budget, with conservation levies paid by tourists ranging from R510 to R575 per person per night. Over the same period, 28 commercial hunters accounted for about 8% of the total income. The question, however, is whether this reliance on hunting remains ecologically and financially viable.

“The complexities of managing a large private nature reserve increase daily,” says an article on Timbavati’s sustainability approach. “A good example of this is the relentless challenge we face in dealing with rhino poaching. In our reserve alone, the costs for security and anti-poaching have escalated by a staggering 900% in the last 6 years, taking up 63% of our annual operating budget…. And while we fight against organised crime and illegal wildlife trade, other serious challenges need to be faced – like integrating the Greater Kruger wilderness and surrounding communities in ways that are sustainable and that reduce the risk of protected area fragmentation.”

Where does hunting revenue go?

Managing a private reserve is a costly endeavour. Conservation funding covers anti-poaching efforts (which alone consume 63% of the annual budget), habitat management, staff salaries, infrastructure maintenance, and ecological monitoring.

In the case of trophy hunting, as with all other revenue generated, revenue goes towards community engagement, anti-poaching initiatives, and reserve management. Regulated hunting also aligns with the Greater Kruger Hunting Protocol, which intends to ensure that hunting practices do not negatively impact the sustainability of a particular species.

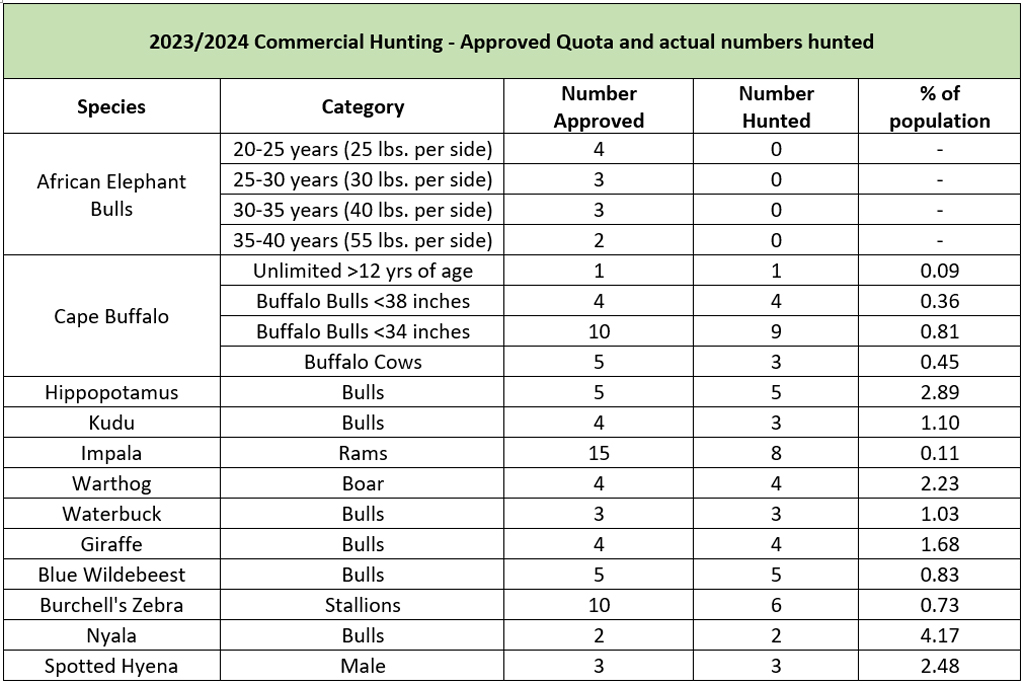

Analysing the numbers: lion, elephant, and buffalo

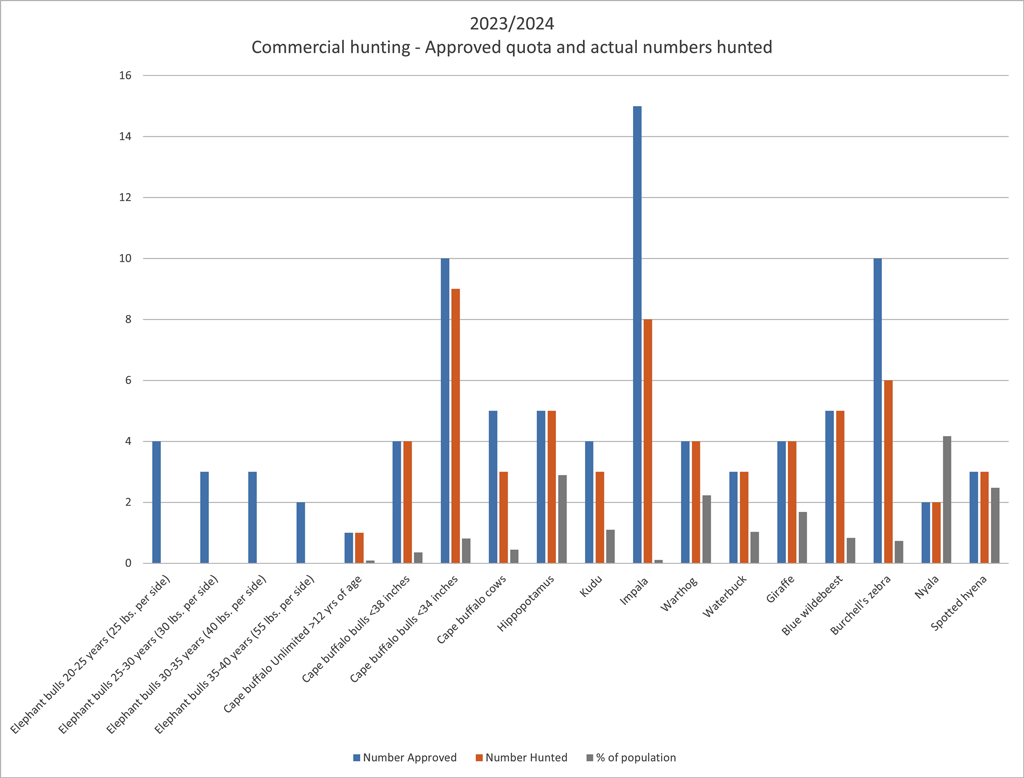

Timbavati adheres to strict quotas when it comes to hunting offtake. In the 2023/2024 hunting season, out of 87 animals approved for hunting by provincial authorities, 60 were hunted, amounting to less than 0.43% of the reserve’s total wildlife population. In the breakdown of species hunted, Cape buffalo made up 42% of the total, while no elephants were hunted due to ongoing CITES-related restrictions on trophy exports. Other animals trophy hunted included hippos, kudu, impala, warthog, waterbuck, giraffe, blue wildebeest, Burchell’s zebra, nyala and spotted hyena.

- Buffalo: A 2022 population study estimated that there were 1,106 buffalo in the reserve at the time. The recommended offtake was 25 individuals, including 15 bulls and 10 reproductive-aged cows. This represents 2.3% of the total population.

- Elephant: No hunting offtake of elephants happened during the 2023/2024 period, although Timbavati did request permission to hunt bulls. The reserve continues to monitor elephant populations closely.

- Lion: There is no specific mention of lion quotas in the most recent data, and Timbavati did not request permission to hunt any lions. Lion hunting remains a contentious issue within the broader Greater Kruger conservation landscape.

Hunting offtake details: age and trophy specifications

Details regarding approved and actual hunting offtake provide clues into the reserve’s approach to sustainable utilisation. No elephant bulls were hunted due to CITES restrictions, but quotas had been allocated for specific age classes based on tusk size per side. On the other hand, Cape buffalo hunting followed trophy measurement guidelines based on population insights obtained through annual surveys.

“Annually, a detailed Cape buffalo population assessment is conducted within the Timbavati,” explains Pierce. This systematic population assessment includes aerial surveys and ground-based observations, assessing physical characteristics such as horn size and body condition, which correlate with age classes.

“Cape buffalo herds are located daily within predetermined sections of the TPNR with a fixed-wing aircraft during the survey period. This systematic way of locating herds and individuals ensured a total coverage of the TPNR during the survey,” says Pierce. A total of 841 buffalo were aged and sexed during the demographic study.

80 out of 252 bulls aged 6 years and older within the sampled population were categorised for potential hunting. Therefore, 31.7% of bulls aged 6 years and older within the sampled population were classified according to the categories within the Greater Kruger Hunting Protocol:

- Buffalo bull < 34 inches: 29 individuals (36.2% of the sampled population)

- Buffalo bull < 38 inches: 39 individuals (48.8%)

- Buffalo bull unlimited: 12 individuals (15%)

Based on these demographics, the recommended offtake included 10 bulls with horn spreads under 34 inches, four bulls under 38 inches, and one bull classified as unlimited. Timbavati says that this approach ensures that older, non-reproductive bulls are primarily selected, minimising genetic disruption within herds:

- Buffalo bull < 34 inches: 10 individuals

- Buffalo bull < 38 inches: 4 individuals

- Buffalo bull unlimited: 1 individual

However, limited direct evidence addresses the genetic impact of selectively hunting older, non-reproductive bulls. One study examining the effects of trophy hunting on Cape buffalo horn size and population structure concludes that there were no apparent effects on horn spread or population dynamics. However, the study warns that while hunting pressures in Greater Kruger are not high enough to affect horn spread, more liberal hunting regulations may lead to artificial selection against smaller horn spreads occurring.

“The selection of older, non-reproductive bulls is guided by the Greater Kruger Hunting Protocol, ensuring that genetic diversity and population stability are preserved,” says Pierce. “While there is limited peer-reviewed data specifically on Cape buffalo breeding cessation, the management approach is based on field data and established wildlife management practices, prioritising the removal of older, non-breeding individuals to minimise genetic disruption.”

The role of culling: Impala management and the arrival of wild dogs

In addition to regulated trophy hunting, Timbavati undertakes culling operations to manage herbivore populations and maintain ecological balance. Impalas, particularly, are subject to culling due to their high numbers and impact on vegetation availability.

During the 2023/2024, “Of the 1,700 impala allocated for ecological offtake during the same period, a total of 822 were removed by management in culling operations, with 426 removed by landowners within the reserve,” says Pierce. This means 1,248 impalas were culled, representing just under 95% of the total offtakes of all species.

Wild dog packs moving into the reserve also influenced impala management decisions. “A decision was, however, taken by Timbavati management to request the removal of only 1,700 of the recommended 2,000 individuals, due to an increase in the number of wild dog packs frequenting the reserve,” Pierce explains. This shows how predator-prey dynamics impact conservation strategies, requiring constant monitoring and adaptive management.

Is this level of hunting sustainable?

From a purely numerical viewpoint, the hunting offtake follows a sustainable approach. The reserve conducts annual aerial censuses and demographic studies to ensure offtakes don’t compromise population stability. But we know that sustainability is about more than just numbers. A truly sustainable approach involves analysis of genetic diversity, ecological balance, and impacts on predator-prey dynamics within a reserve.

The debate around whether hunting in Timbavati is sustainable goes beyond this reserve’s borders. Timbavati’s open ecosystem means hunting decisions impact animal populations moving between private reserves and Kruger National Park. While a controlled hunting offtake of buffalo may not threaten the overall buffalo population, hunting apex predators like lions (if permitted) can disrupt pride structures and alter ecosystem stability. However, as noted above, Timbavati did not request lion offtakes for the 2023/2024 period.

“TPNR follows stringent scientific protocols to ensure sustainable hunting practices,” says Pierce. “These practices align with the overarching goal of maintaining ecological balance and preventing habitat fragmentation. The Greater Kruger landscape thrives on maintaining large, interconnected habitats, and TPNR’s practices are aligned with this principle.”

The bigger question: why continue trophy hunting?

However, the glaring question we have to ask is – if trophy hunting contributes only 8% of Timbavati’s budget and comes with ecological and reputational risks, why continue?

Timbavati’s strategy of economic diversification and land-use philosophy says that trophy hunting remains beneficial due to:

- Economic insurance: “Timbavati continues to include trophy hunting within its economic model because it provides financial stability during times when tourism revenue may be disrupted, such as global crises,” says Pierce. “While it only contributes 8% of the budget, its value lies in economic diversification, mitigating the risks associated with relying solely on photographic tourism. [Trophy hunting] is a strategic financial buffer during economic downturns.”

While photographic tourism provides the lion’s revenue share, it is vulnerable to market fluctuations. Global crises, like the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, highlighted the fragility of tourism-dependent economies. Although the epidemic was geographically distant from significant safari destinations in Southern and East Africa, photographic tourism in these regions experienced significant declines due to widespread travel fears. In contrast, trophy hunting operations continued with limited disruption. This disparity is attributed to the hunting market’s distinct clientele and operational model, often less susceptible to global travel apprehensions. Timbavati management argues that trophy hunting provides an alternative revenue stream that is less sensitive to seasonal downturns. “It is crucial to acknowledge that while hunting revenue is comparatively smaller, it offers resilience when tourism income is disrupted, such as during global crises,” says Pierce. But as hunting only contributes 8% of Timbavati’s revenue, its overall contribution would still be limited in times of crisis, considering its minimal impact on the overall budget. - Low human footprint: Unlike photographic tourism, which requires lodges, vehicles, and staff, there is a standing belief that trophy hunting has a lower ecological footprint – higher fees for fewer feet through the door. “Hunting’s lower human footprint compared to high-volume tourism helps balance the environmental impact, reinforcing the need for diverse income strategies rather than single-source dependency. Our aim is to maintain a diversified revenue model to ensure long-term conservation success and financial resilience,” says Pierce. A few hunters generate more considerable revenue. While hunting utilises some existing tourism infrastructure, such as roads and lodges, it does not require the continuous game drives and vehicle movements for high-volume photographic tourism. A single hunter contributes financially at a scale comparable to many photographic tourists but requires fewer game drives, staff, and vehicles, resulting in less continuous impact.

- Community initiatives: Timbavati reports that some hunting revenue is allocated to local community initiatives.“A portion of the revenue from regulated hunting is allocated to community projects in neighbouring areas,” says Pierce. “As highlighted in community engagement sessions, the most pressing issues for residents around Greater Kruger include employment, education, and reducing human-wildlife conflict. Presenting hunting as a practical tool that supports these socio-economic priorities can help contextualise its continued inclusion within the reserve’s financial model.”

By involving neighbouring communities in conservation benefits, the reserve is likely to foster support for wildlife protection. However, one can argue that this is not a differentiator because tourism revenue also contributes to community projects and involvement. - Political and policy considerations: While it may be a bitter pill for some to swallow, hunting is embedded in South Africa’s conservation policies as a tool for sustainable utilisation. It is important to note that Timbavati has demonstrated a commendable level of transparency by openly sharing data on sensitive issues like hunting when requested – setting a valuable precedent that other trophy hunting operations would do well to follow.“We are confident that our management practices and our robust monitoring and evaluation tools support every decision we make, whether it be about hunting, photographic tourism, or any other conservation management decision,” says Pierce.

The future of Timbavati’s funding model

Timbavati’s reliance on trophy hunting is far lower than in previous decades. The reserve has made strides in balancing its budget through photo tourism.

“TPNR has taken progressive steps to reduce dependency on hunting revenue,” says Pierce. “Transitioning to alternative funding sources is ongoing, but the current model ensures both financial sustainability and ecological balance.”

As conservation costs continue to rise, eliminating hunting may not be a practical solution. Instead, the focus should be on ensuring hunting quotas remain science-based, transparent, and aligned with ecosystem sustainability. It will also be an essential exercise to compare Timbavati’s 2024/2025 numbers when they are finalised.

The long-term challenge for Timbavati – and other private reserves in the Greater Kruger – will be to explore alternative funding models.

Want to go on a Timbavati safari? Browse our safaris to Timbavati here. Or longing to visit Kruger? Check out our ready-made safaris to Greater Kruger.

Further reading

- Take a deep dive into the reserve that makes up one of Africa’s most iconic safari destinations: Greater Kruger, South Africa

- Where to find revenue to fund much-needed anti-poaching operations? Don Scott explored what an increase in Timbavati levies meant for conservation

- Does the trophy hunting of elephant bulls with large tusks lead to the decline of Africa’s tuskers? We examine the science

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()