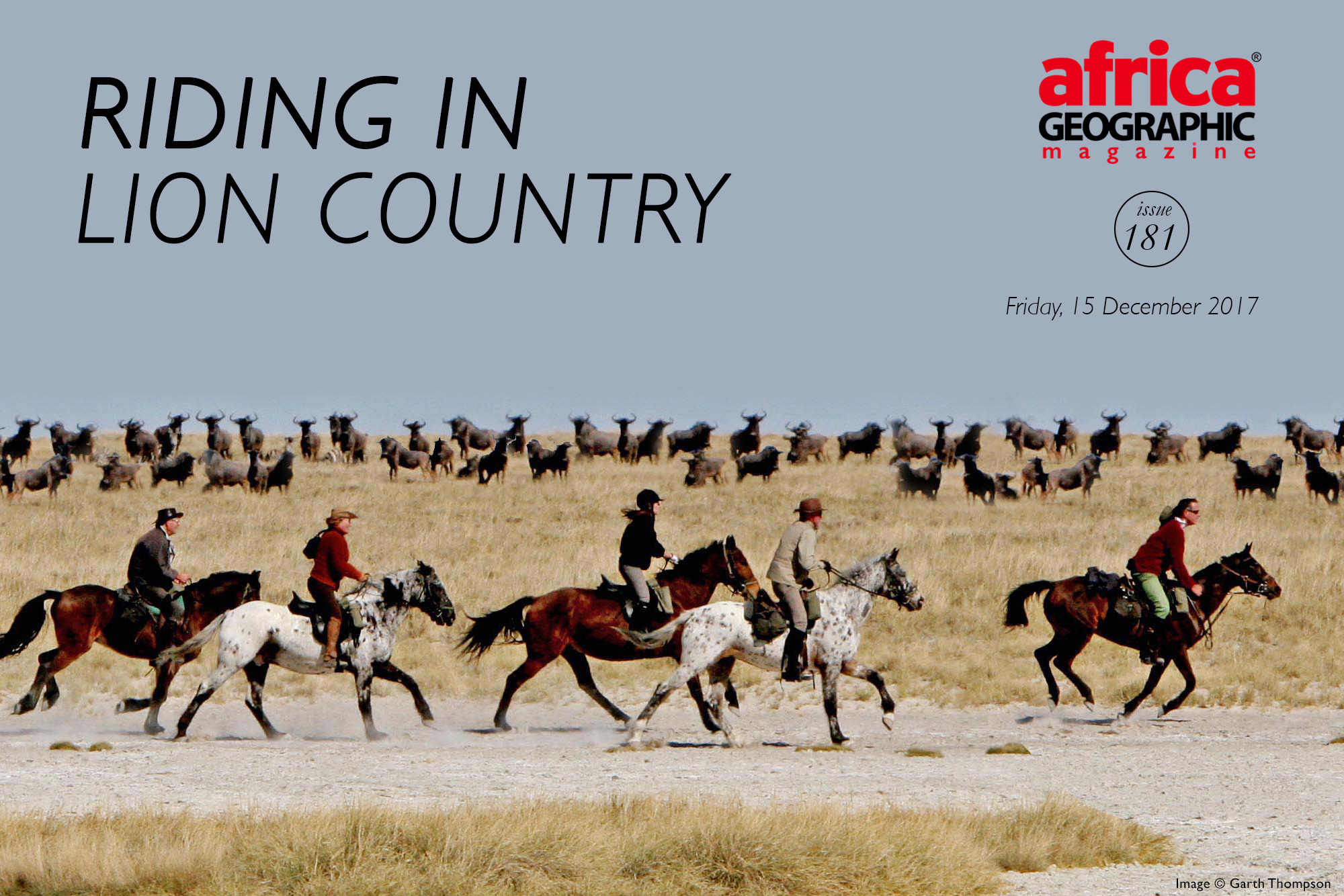

On horseback in Makgadikgadi Pans, Botswana

Equestrian types tend to come with a few traits that, while charming to fellow horsey folk, are unbearably irritating to those not of a horsey nature. One such quirk is the devout belief that having ridden one way, you probably know – better than most – how to ride another. We also have an unwavering belief that we know exactly what to expect from most types of rides, regardless of whether or not we’ve participated.

Indeed, that was the case for me. I’ve ridden since the age of two when I was plonked onto the back of an obliging Shetland pony. Since then I’ve ridden eventers, dressage divas, highly-strung showjumpers, focused polo ponies, and wild ex-racehorses. So, when the opportunity arose to go on a horse safari in Botswana, I knew exactly what to expect (not because I’d ever done one before of course, but because I’m a horse person).

I thought we’d be riding around safe game only – meerkats would probably be the only carnivores we’d encounter; the horses would be dead to the leg, gone to the world, and know exactly where to walk, where to stop, and where to trot (if indeed such speed was allowed). I also knew jolly well that this was to be a glorified trail ride – a bit boring perhaps, but an excellent opportunity for those all-important insta-snaps and an experience to supplement future conversations.

Or, so I thought.

Being a horse person, I insisted on taking my own gear: a lightweight ventilated helmet, jods, chaps, riding boots, gloves, and even a GoPro. My husband (himself a very experienced safari-goer and former guide) raised his eyebrows further north with each pristine piece of clothing I produced and folded carefully into my canvas bag. I should point out at this stage that our luggage allowance was minimal, but he knows better than to argue with a horse person. I could not have felt more ready for my impending horseback safari… I was not ready.

The evening before my ride we went on a game drive through Botswana’s Makgadikgadi salt pans, and amongst the abundance of wildlife we saw lions. As we sat and watched the sun set behind a huge male, his lady friend began to call.

“She’s calling to her mother,” our guide explained.

“Where is her mother?” I asked.

“Somewhere on the other side of the pans,” came the relaxed response as we watched the golden cat slink off towards the pans.

As we pulled up for our evening drinks a short while later, our guide checked carefully that neither lion was tucked behind the foliage nearby before releasing us from the vehicle. Still, in the haze of wine and excited lion chatter, we thought little more of it.

Horse safari day dawned with the pastel-infused skies that only Botswana can produce. We were travelling with our young daughter, so lengthy rides were off the table for me; I’d signed up instead for a sunset ride that evening.

We spent the morning on another drive, during which we enquired about the whereabouts of the lions we’d seen the previous night. Our guide wasn’t sure exactly where they were since they’re nocturnal and had moved overnight, but there was plenty more wildlife for us to see – happy hours were spent watching elephants feed on and destroy the trees at the edges of the pans.

Aren’t there lions out here?

When the time came for my ride, we were driven through an electric gate and up a drive to where the horses lived. I saw a smile play on the lips of the horse guide as he watched me hop from the 4×4 vehicle, GoPro strapped to the top of my helmet like evolution’s most dastardly attempt at an antenna.

Consummately professional though, he greeted me without so much as a snigger, and introduced me to my mount – a chestnut named Socks.

I felt rather smug to see that Socks looked every inch the trail horse, standing calmly as his girth was tightened, and not batting an eye at the strange contraption protruding from my head. I was busy congratulating myself on my correct intuitions about the ride when I realised that my guide, Levius, was heading for the gate through which we’d driven.

Without a moment’s hesitation, he rode into the park where we’d watched lions the night before, and where that very morning, our guide had been unable to confirm their location. I’d imagined a sedate amble behind the safety of the game fence, and now here we were, riding straight into lion country.

Suddenly, aware that I genuinely had no idea what to expect from the ride, I noticed a chunk missing from Socks’ ear; as we rode deeper into the reserve, it began to look increasingly jaw-shaped.

“Aren’t there lions out here?” I eventually squeaked, hoping I didn’t sound too terrified.

“Yes, there are,” came the cool response. “That’s why I have my banger.”

I glanced down to Levius’ hip, attached to which was a small, almost gun-like contraption.

“It makes a loud firing noise that frightens lions away,” he reassured me. “But the horses know when there are lions. They smell them, and they won’t want to go that way.”

I furtively scanned the horizon to ensure that we would spot the big cats with plenty of time for Levius’ banger to be deployed, should the need arise. If there were lions around, Socks had yet to smell them.

I’ve ridden many horses, and in my experience, most find plastic bags more terrifying than genuine danger. I desperately hoped that Socks’ intuition was more finely tuned. I felt confident that Levius had the faster mount, so if a lion did give chase dear old Socks and I were surely supper.

Levius, it turned out, hailed from a small village in Botswana and now guides for a company called Ride Botswana who operate between the Uncharted Africa camps here in the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park, and routes through the Okavango Delta. He’d never been interested in horses until David Foot (the owner of Ride Botswana and safari guide) took him under his wing and taught him how to ride and how to guide. Still, he’s now every inch the horse person, with leather gaiters perfectly tailored to fit, and gloves that made me decide to upgrade my own.

To read more about the safari guide on horseback, continue reading below the advert

He’s also nothing that I’d expected a trail guide to be because he isn’t. He’s a safari guide who happens to do the job on horseback. There was none of the boredom I’d encountered on treks through the Welsh hills on family holidays. Levius loved his job, his horses, the area; he rode beautifully despite likening his style to that of a cowboy. His mount was a former racehorse intriguingly named Bon Jovi, and with plenty of spirit (horse person speak for ‘you’ll probably fall off’), but instead of pulling and hauling the thoroughbred, his hands remained soft and gentle – showing balance, kindness and confidence that many a more experienced rider lacks.

“Do you ever worry about lions coming for the horses during the night?” I queried, unable to shake the big cats from my mind.

“I sleep with my tent open so that I can hear,” he answered. “They are my babies, and I have to take care of them.”

Despite the dedicated care and commitment that Levius showers upon his steeds, he’ll admit to a close call where lions are concerned, telling me that he’d come out of his tent to check on the horses one night only to find a lion playing with a piece of tarpaulin. He assures me that his trusty banger did its job, seeing off the enormous cat, but it’s not an experience he’s keen to repeat.

“You know, we did see lions here last night,” I offered, concerned that he might not have realised they were in the area.

“Where were they?” he asked.

“Well, I’m not exactly sure, but one was under a palm tree,” I offered.

Levius’ face cracked almost open with a wicked grin as he gestured towards the landscape, which is punctuated every few metres by palm trees. It wasn’t, I suppose, a particularly helpful landmark to offer.

After some time riding through the grasslands, we came to the pans. The Makgadikgadi salt pans are the world’s most extensive salt pan system, and quite a sight to behold. Despite having ridden through the sea, river, woodland, countryside and much more, to ride across the pans was incomparable.

Animals, grassland and the moon

The vast, silent landscape could very well be likened to standing alone at the top of a ski slope and is almost exactly how I imagine it might be to stand on the surface of the moon. This was unlike any trail I’d ever ridden, and Levius dispelled my expectations once more by suggesting we pick up the pace. As we progressed through the horses’ gears, I saw Bon Jovi starting to get excited, but his gentle rider was unfazed, expertly guiding his mount instead of fighting him.

Socks, meanwhile, was also surprising me with his turn of speed and love of life, waiting for commands rather than merely following the horse in front, and offering a keenness rarely seen on trails and treks.

We reached the edge of the pans and slowed back to a walk as we proceeded through the grasslands; the guide and horses were fit enough to hit their strides straight away, while I did my best to conceal my lack of fitness. Taking pity on me, Levius paused alongside an aardvark hole, and kindly took his time to explain how they get utilised by a variety of different species.

Feeling fine, we continued through the grasslands, chatting as the sun began to sink through the sky, painting the horizon with strobes of orange and pink.

Through the splashes of colour and dust, we began to make out the shapes of wildebeest and zebra, making their way to congregate in the safety of the open for the night.

We rode towards the animals, and I was waiting for them to scatter, but they didn’t, and before long, we were almost upon them.

“They don’t worry about the horses,” explained Levius. “We can get much closer to them like this than in a vehicle.” So we were able to spend time with both species, watching their interactions and dynamics. While they were aware of our presence, they didn’t seem to mind it one bit, and it felt a wonderfully unobtrusive way to be around them.

Eventually, with the light fading, we left this intriguing mixed herd who’d welcomed us to join them and turned back towards the camp, taking advantage of a dirt track along which we could enjoy a final canter, the horses even faster in the direction of home. In a flurry of hot African dust, we reached the game drive vehicle in which my husband and daughter sat, waiting to meet us with drinks and an array of snacks. The car seemed so cumbersome after my adventure with Socks.

“What would have happened if we’d met a lion?” I felt suddenly brave enough to ask, now that the vehicle was within hopping distance.

“I’d have stood in front of it until it went away,” explained Levius.

“What if it didn’t go away?” I pressed.

“Then I’d have stood there for a very long time,” he smiled.

The final horse straw

There remained one final question that I was reluctant to ask though, all too aware that when horses are business, the answer is rarely kind. “What happens to the horses when they can’t be used for safaris anymore?” I grudgingly enquired.

“They go to rest,” replies Levius, but he looked confused when my face fell. Understanding my dire assumption, my guide reassured me, “there’s a mare in Maun who’s in her thirties. She’s worked hard, so now she relaxes.”

My heart sang. I bade Socks farewell, seeing this brave, sweet horse in a new light as the horizon flashed its kaleidoscope of colours behind him. Gone was the trail horse I’d first imagined him to be. This Socks was brave, independent and capable of negotiating lion country with only a nicked ear.

To read more about the final leg of this horse riding safari, continue reading below the advert

As we watched Levius ride and lead the duo back to the safety of camp, I caught sight of a cat-shaped piece of gold in the distance.

“Lion!” I shrieked, at which my husband and our safari guide chortled in unison: “That’s a termite mound.”

I never did find out whether Socks’ ear was bitten by a lion, and I know that Levius would never have allowed such a thing to happen. Still, when I tell the story around dinner tables to fellow horse people, the ear was bitten fully off before brave Socks fought his way to freedom, or at the very least, a happy retirement in Maun.

As for the lions, I didn’t see them again, but I’m pretty darn sure that they were watching us for every step of the ride. ![]()

Makgadikgadi Pans info

SIZE

Makgadikgadi Pans is a 16,000 km² network of natural salt pans and surrounding Kalahari Basin bushveld in Botswana. Together, these pans comprise one of the largest salt pan ecosystems in the world – with the Sowa, Nxai and Nwetwe pans being the largest individual pans.

The Makgadikgadi Pans National Park (3,900 km²) and Nxai Pan National Park (1,700 km²) together cover one-third of the Makgadikgadi Pans area. The two primary sources of seasonal water to the pans are the Boteti and Nata rivers.

HISTORY

The pans are the dried-up lake bed of the ancient Lake Makgadikgadi that once submerged the entire area. Human habitation is evident here since the early Stone age, and the area is rich in archaeological history, displaying tools and other remnants of early man.

Chapman’s Baobab, an iconic landmark of the Makgadikgadi landscape that has stood the test of time for nearly 4000 years, was made famous after a Makgadikgadi crossing by celebrated explored Dr David Livingstone in the 19th century. Unfortunately, the giant tree crashed to the ground on 7th January 2016 but is still regarded as an impressive sight. Other noteworthy icons are the rocky Kubu Island in Sua Pan and Baines baobabs in Nxai Pan.

FLORA

The salt pans themselves cannot support major plant life, and the only flora here is comprised of a very thin layer of blue-green algae. However, the dry salt pans are surrounded by salt marshes, grassland and shrubby savannah.

WILDLIFE

During the dry winter months, most wildlife will be found to the west of the Makgadikgadi Pans, near the Boteti River. After the first rains in November, the second largest zebra migration in Africa occurs as zebras and wildebeest move in an easterly direction, to the grassy areas north of the pans. Other large species found in the area include oryx, springbok, eland, red hartebeest, giraffes, elephants, lions, cheetahs, leopards, hyenas, white rhinos and wild dogs.

The pans attract large numbers of waterfowl when full of water, and are an essential habitat for one of only two breeding populations of greater flamingos in southern Africa.

SEASONS

Makgadikgadi sees a tremendous environmental and landscape change between the seasons. In the drier months, between April and November, the landscape is dry and arid with little life. During the rainy season, between November and March, the landscape is transformed into a thriving paradise for both flora and fauna.

TRAVEL

For accommodation options at the best prices visit our collection of camps and lodges: private travel & conservation club. If you are not yet a member, see how to JOIN below this story.

The pans themselves are only accessible in the drier months. This attraction alone makes the months between April and November a more popular time to travel. However, January through March is popular as well – to witness the second largest migration of animals in Africa on the grassy plains north of the pans.

Pru’s Makgadikgadi Pans Accommodation

Camp Kalahari is a traditional safari camp on the fringes of the Makgadikgadi Pans. It is designed in the old, Meru-style of safari camps reminiscent of the pioneer explorers of the African continent. The camp has ten of these spacious, luxurious tents and is the perfect place to relax, unwind and cool off after a day exploring the hot and sweltering pans.

Activities here include bushwalking with local Bushmen, a visit to the famously fallen Chapman’s Baobab, and safaris to witness the last-surviving migration of animals in southern Africa.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Originally from England, Pru Allison first completed a degree in theatre before furthering her studies in animal behaviour. This proved a winning combination for the spectacle of the natural world when love brought her to Africa and a new home in Cape Town.

Originally from England, Pru Allison first completed a degree in theatre before furthering her studies in animal behaviour. This proved a winning combination for the spectacle of the natural world when love brought her to Africa and a new home in Cape Town.

She’s written for a range of magazines in a variety of countries, and wildlife highlights so far include sitting with baby brown hyenas in their den in Namibia, meeting giant tortoises in Seychelles, finding snow leopards in the Himalayas, and following wolves in India.

Pru has ridden horses since the age of two, and can currently be found scouring tack shops for a helmet small enough to fit her baby daughter so she too can saddle up. You can follow her on her Instagram account.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()