Written by Francesco Nardelli – IUCN/SSC Asian Rhino Specialist Group / Save the Rhino International

*The views expressed are those of the author

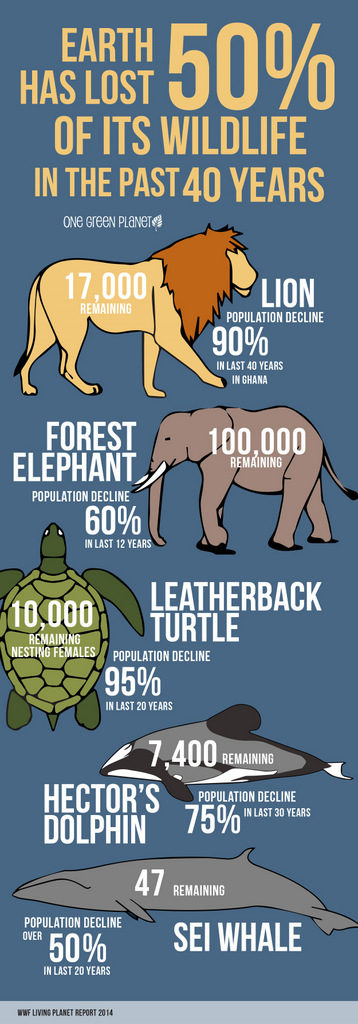

In the middle of the sixth mass extinction, when 50% of the living species are at risk of extinction due to the ever-growing, destructive human hands, six rhinoceros species are at the tip of the pyramid, and are among the most endangered species on Earth. Africa, in particular, is troubled by rampaging poaching. Countries with rhinos, NGOs, rhino owners, conservationists, ‘celebrities’ and corporate business owners are trying several schemes to save the rhinos: Dehorning, horn poisoning, synthetic horns, horns embedded with micro-cameras or chips, educational campaigns and intergovernmental agreements. These have yet to bear significant results to eliminate the poaching-trading plague which is killing rhinos by the thousands.

The time has come to change some of the solutions, proven to be ineffective, with new strategies to save the last pachyderms.

The Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) is nearly extinct; just three Nile rhinos (Cerathoterium cottoni) Groves et al. 2010, exist; the last sixty Javan rhinos (Rhinoceros sondaicus) are critically endangered; the black (Diceros bicornis) and the Indian (Rhinoceros unicornis) rhinos are surviving in a few thousands. The white rhino (Cerathoterium simum), the second largest mammal on Earth, seems to hold on at reasonable numbers despite rampant poaching.

The killing fields, trading routes, smuggling tricks, countries involved in trafficking, location of the exit-entry points, and identity of the people involved are all recognised. Conservation action plans are completed and a number of options are on the table, but few are totally implemented. Lack of political will, of funds, of ‘education’, overwhelming corruption, are exposed as undeniable causes of the disaster. Nevertheless, the scenario emerges without one collective, cooperative and factual global action to save the rhinos.

African rhinos versus poaching

The majority of African rhinos suffer from the plight of poaching, and at first sight it would appear that by simply removing the horn the problem is solved: rhinos should be worthless to poachers. However, there are numerous cases where dehorning has proved insufficient to prevent rhinos from falling victim to poachers. After any dehorning exercise, a stub of horn will remain, and although poaching is made less profitable, the sad reality is that poachers will still kill for a horn stub due to its high value – or merely to end their chase ‘successfully’.

What is there to say about poisoning, tagging or inserting micro cameras into the horns of live animals: good intentions, but ineffective? On a large scale, those procedures consume too much time and funds and pose too great a risk for the animal’s health.

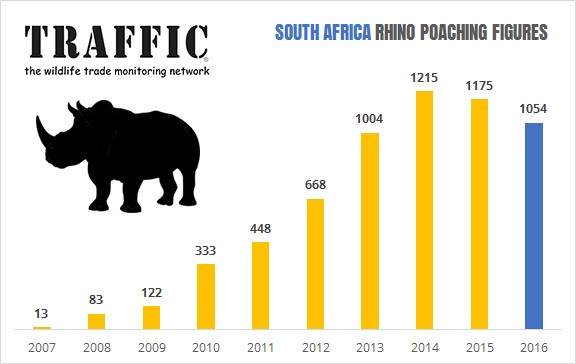

Are those initiatives deterrents for daredevil poachers? South Africa’s Minister of Environmental Affairs, Edna Molewa revealed that “from January to June 2017, 529 rhino have been poached, compared to 542 over the same period last year”(Brandt 2017). Such a similar figure has become nearly constant since 2013 (Table 1), to confirm that poachers need other kind of deterrents.

What it is of further concern is that legal trade in rhino horn has resumed in South Africa, ostensibly to raise funds for protection and to bring poaching to end (DEA 2017a).

Two fundamental questions rise spontaneously: why and how is legal trade in rhino horn going to stop poachers and traders?

Rhino horn should not be trafficked, just like pangolin scales, shark fins, giant clams, ivory, whale meat, etc. Wildlife trading only favours present and potential dealers who exploit animals for their livelihoods and lifestyles – in fact they refuse to look at any alternative which may work for the rhinos.

To complicate the efforts, there is the ever-increasing presence of ubiquitous corruption.

A primary predicament is the obsolete and unethical theory that “wildlife has to pay for itself”, hence to be considered as a commodity like corn, wheat, rubber, oil, etc. That approach has evolved in all sorts of destructive activities to become the principal reason behind habitat destruction and wildlife extinction. Too many people still have this primitive consideration for living beings, and that it is a fatal correlation for the rhinos and other species, unless their alive or dead status are clearly divided (e.g. a touristic safari is not a trophy hunting safari).

Several scientific studies prove and provide irrefutable evidence that non-human animals are sentient and conscious, thus they have rights to be respected, their life in primis (Allen & Bekoff 2007, Mountain 2012, Bekoff 2013, Grasso 2014, Jones 2015, de Waal 2016).

On April 30, 2017, The New Yorker reported: “More than six thousand tigers live on Chinese farms that often raise them in concrete pens solely for their parts”. While such harvesting may seem to take pressure off wild populations, tiger experts indicate the opposite: “Tiger farms actually legitimise the business”. The article’s author, John Goodrich went on, “users always think wild is better than farmed, so they will just pay more for wild”.

Zhou Fei, the head of China’s office for TRAFFIC, the foremost organisation monitoring the global wildlife trade, states: “China’s domestic ivory ban is a milestone for the conservation of wild elephants in Africa. Nevertheless, if even a fraction of Chinese consumers want to collect ivory tchotchkes, or grind up rhino horn for clueless medicinal properties, global animal populations will continue to suffer” (Beech 2017).

Expert Bryan Christy has comprehensively exposed the rhino horn trade situation and reported a convicted criminal’s (would-be-legal-trader) blunt confirmation of his dishonest intentions (Christy & Stenton 2016).

Legalising the domestic trade

A significant example of the aphorism, “they have a few ideas but… confused”, is the recent attempt to legalise the rhino horn trade by some countries.

To legalise the domestic trade and eventually the export of rhino horn is likely to bring down national and international efforts to protect rhinos, not only the African species. In reality, there is no domestic consumption of rhino horns in Africa – are trade is smuggled offshore.

Because of CITES Appendix II listing of the South African and Swaziland’s white rhino populations, some legal trade has been possible, though only for limited numbers of hunting trophies and live rhinos. In addition, the end of the 2009’s trade moratorium is surely not good news for the rhinos, especially when there is already a well-documented link between the sale of wildlife ‘born’ in breeding farms and illegal trading (Nuwer 2017).

On June 24, 2017, John Hume, the major private rhino owner in South Africa, announced that in the middle of August 2017 two online global auctions were going to sell 500kgs of rhino horns, taken out from his stockpile (Carnie 2017).

Less than a week later, on 30 June CY, the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) clarified that rhino horn may not be traded internationally (DEA 2017c). At the time of writing, a last minute auction was held, with poor results. Easy to predict: what trader would buy the same item at a higher price than the amount he/she is used to paying? The DEA explained that only domestic trade will be allowed, listing a series of conditions clearly dictated by haste rather than logic, only to forget that a domestic market for rhino horn does not exist.

Hume’s victory is a slap to those countries that voted against the traffic of rhino horn at the CITES CoP17 in Gauteng (2016), to conservationists, to rangers’ family members, people killed to protect rhinos – 100 a year (Gill 2017) – with serious repercussions on the active Rangers (Moreto et al. 2017), but a great victory for the small number of rhinos farmers, the latent traders.

Meanwhile, the DEA has yet to answer a series of sensible questions by Save the Rhino International (SRI 2017):

• Who will the buyers be?

• Is it being considered for financial or conservation reasons?

• Why – given that judges had so far agreed with the challenge to the moratorium on domestic trade but based on a technicality (that the government did not follow due process) – hadn’t the South African government used this time to draw up a new moratorium that would be announced through all the correct channels and with an adequate notice period?

• Does South Africa have the funding, capacity or expertise to regulate a legal domestic trade and continue to police an illegal one?

• How would a domestic trade affect court cases against those accused of rhino horn trafficking?

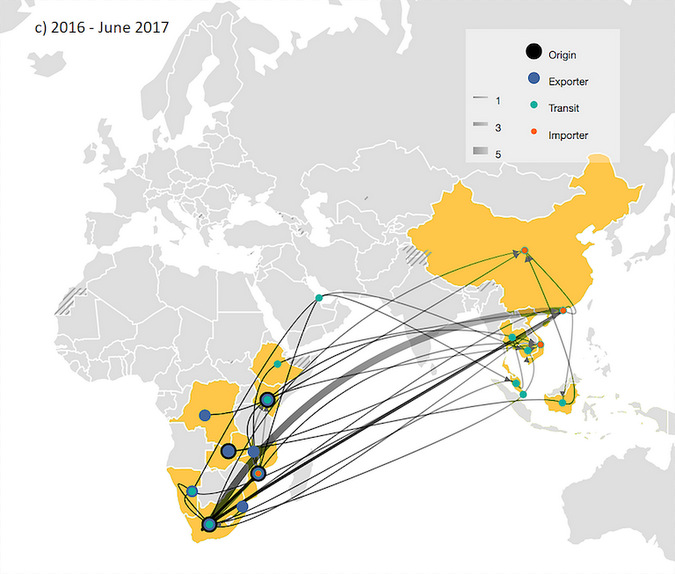

Author’s thought: maybe decision-takers wish to create a brand new market or a huge loophole for smugglers to sell horns to real consumers? The two biggest markets for illicit wildlife products are in Asia; in particular China and Vietnam are the main culprits, but the problem is ultimately global.

If the new regulations will become law, it is not just South Africa that will become a de facto market, open to internal and external rhino horn trade. In West and Central Africa, the vast area where insurgents and terror groups are most active, the western black rhino, the Nile rhino, and elephants are extinct or very close to disappearing – all killed by poachers.

In the last three years alone, over 3,500 rhinos (SRI 2017), circa 20% of the total population, were hunted down for their horns. The conservation of the two African rhinos species is now in a muddle – in a state of affairs resulting already in the loss of three rhinos a day (WWF 2017).

Results

The Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA b) on 27 February 2017 stated that “During September 2016, a rhino survey using the scientifically accepted block count method* recorded that a total of 6,649 – 7,830 white rhinos lived in Kruger National Park. A total of 1,054 rhinos were poached in 2016, compared with 1,175 in the same period of 2015, a decline of 10.3%. Specifically for the Kruger National Park (KNP), a total of 662 rhino carcasses were found in 2016 compared to 826 in 2015. This represents a reduction of 19.85% in 2016. This despite a continuous increase in the number of illegal incursions (2,883) in the Kruger National Park. A total of 6,649-7,830 (medium 7,239) White Rhinos (survive) in the Kruger National Park, a significant lower data given the 8,365-9,337 (medium 8851) of 2015.”

*Initially the total area is divided into blocks or transects. A block is known as a sampling unit. Therefore it is unlikely all the animals of the sample area are to be seen and counted. The total population estimate is considering that animals are distributed evenly, by multiplying the average number of animals on the sample for the whole territory. For example, we know that animals congregate in areas of good habitat (and where there is water), so an accurate census has to consider this distribution as uneven to obtain accurate and precise results.

This means, as per media numbers, that the KNP rhino population decreased at a minimum 26,5% in one year. This high percentage could very well be ascribed to more rhinos lost than those recorded. Worse, the moment in time when losses exceed the births means the species’ steep descent to extinction.

Even assuming that in the population of the KNP, 30% are breeding females (about 2400), that every three years a calf is born from each female; that all newborns reach adulthood; that 2,400 females produce 800 rhinos over a twelve-month period. In this (over-optimistic) case, the birth rate oscillates at around 11%, compared to a mortality rate of 26,5%, this is unsustainable for the survival of a species.

From these calculations, based on media numbers, it results from a loss of around 1,600 rhinos just in KNP in 2016, against an official figure of 1,054 rhinos throughout South Africa.

According to Keith Somerville (2017), “There are at most 5,458 black rhino and 21,085 white rhino, of the latter between 19,000 and 20,000 in South Africa”. Too many, according to the author’s calculation.

In any case, figures are not supported by a much-needed scientific comprehensive survey.

Furthermore, all subspecies of the black rhino (Diceros bicornis) are in the CITES Appendix I, therefore they should be excluded from DEA’s new regulations. Nevertheless, the South African population of the eastern black rhino (Diceros bicornis michaeli) is included, because the animals were introduced and listed as invasive species. To reinforce that deviant concept, six black rhinos are going to be captured in South Africa, transported and released in Chad, a country that lost its last rhino in 1972 (AFP 2017).

Illegal wildlife trafficking

Since security agencies are strengthening counter-terrorism measures – for instance, better control of offshore bank accounts – terror-armed groups are increasingly turning to new sources of income such as wildlife trafficking. The rise of the price and trade in ivory and horn – fuelled by growing demand and enabled by weak law enforcement and porous borders – has led to an increased militarisation of poaching that also fuels conflicts, to become a cause of forced migrations from fragile African countries.While the international community battles terrorism and tackles mass migrations, the time has come to also consider courageous action for the conservation of endangered species. Those major tragedies are linked, and by tolerating poachers who traffic in rhino horn and ivory, we are neglecting a relevant aspect concerning our world’s security.

Together with drug trafficking, illegal wildlife trading is among the main sources of revenue for terror groups, such as the Lord’s Resistance Army in the Central African Republic, the Sudanese Janjaweed or Al-Shabaab.

A comprehensive, planned and coordinated global strategy is of the essence. The time is now to capitalise on this unique opportunity in history in which several countries are looking for consistent, dynamic and timely control in going after the omnipresent criminal organisations that traffic in narcotics, human migration and terrorism.

Secret services play major roles in the implementation of the anti-terrorism strategy and their activity should be further expanded into wildlife illegal trading, to stop a major source of money for all the factions involved.

Responses so far to the alarming pace of wildlife crime have been inadequate for the scale of the problem, and mostly are based on defensive rather than offensive strategies. As a matter of urgency, stringent controls and rigorous protection on the ground should be fulfilled, along with methodical conservation procedures.

Evolution of poaching

Meanwhile, poaching is evolving. Very recently, an investigation has determined that criminal networks smuggling rhino horns out of Africa are turning them into jewellery to evade detection in airports. A comprehensive report by TRAFFIC, released in September 2017, documents that seizures have typically comprised whole horns, or ones simply cut into pieces. Chinese e-commerce sites are selling rhino horn beads, bracelets and other similar jewellery – all status-symbol products rather than traditional paraphernalia (EIA 2017, Ong 2017).

Conclusion

Substantial army deployment is quite desirable, though the magnitude of the territory makes this action, unless substantial, more a palliative than a long-term solution, not to mention unpredictable consequences (Walton 2017). However, by promoting local communities’ involvement and participation, by exercising the ranger forces engaging special army units to train and assist them, the international community could disrupt traffic networks, the illegal trade in endangered wildlife and its consequences.

In the absence of reliable data, a comprehensive African rhinos census should be implemented, not only in South Africa, as it was recently completed for the savannah elephant (Loxodonta africana), (Chase et al. 2016).

The claimed 20,000 white rhinos are the progeny of a tiny and critically endangered population of just two dozen individuals, hence in a genetic condition susceptible to fall into an extinction vortex. Once samples are collected, a Population Viability Analysis (PVA) should also be performed by local and foreign specialists.

A resolution to extend full legal protection to all elephants and rhino species, subspecies and local populations, upgrading them to CITES Appendix I, may well close all the loopholes which are still accessible for trading in Appendix II species.

Nearly all the available information comes from South Africa, thus a good sign of concern by that country, so that they should lead the way out of the present, awful situation.

It is time for all the involved governments to concur on new regulations in order to obtain concrete results for the benefit of rhinos and local human communities. Fresh negotiations should begin right now, founded on realistic chances of success.

References

Agence France Presse (AFP) 2017. Black rhino to return to Chad after South Africa deal. Online 09 October 2017.

Allen C. and Bekoff M. 2007. Animal consciousness. The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness. 58-71.

Beech H. 2017. Pandas, Pangolins, and China’s Fitful Attempts at Wildlife Conservation. The New Yorker. Online 30 April 2017.

Brandt K. 2017. Rhino Poaching Deaths Down – Minister Molewa. Eyewitness News (EWN). Online 24 July 2017.

Carnie T. 2017. 500 kg of rhino horn up for grabs as South African breeder hosts first ever online global auction. Sunday World. Online 24 June 2017.

Chase MJ, Schlossberg S, Griffin CR, Bouché PJC, Djene SW, Elkan PW, Ferreira S, Grossman F, Kohi EM, Landen K, Omondi P, Peltier A, Selier SAJ, Sutcliffe R. (2016) Continent-wide survey reveals massive decline in African savannah elephants. PeerJ 4: https://doi.org e2354/ 10.7717/peerj.2354

Christy B. & Stenton B. 2016. Special Investigation: Inside the Deadly Rhino Horn Trade. National Geographic Magazine. Online: October 2016.

Department of Environmental Affairs Republic of South Africa (DEA) 2017 a. Draft regulations for the domestic trade in Rhinoceros horn, or a part, product or derivative of Rhinoceros horn. Department of Environmental Affairs, Republic of South Africa. Gazette Vol. 620, 8 February 2017 No. 40601

Department of Environmental Affairs Republic of South Africa (DEA) 2017 b. Minister Molewa highlights progress on Integrated Strategic Management of Rhinoceros. DEA statement 27 February 2017.

Department of Environmental Affairs Republic of South Africa (DEA) 2017 c. Department of Environmental Affairs clarifies that rhino horn may not be traded internationally. Media release 30 June 2017.

de Waal F. 2016. Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? W.W. Norton & Co. United States. 352 pages.

Environmental Investigation Agency EIA 2017. Illegal Trade Seizures Mapping the Crimes. eia-international.org; Online 18 September 2017.

Gill V. 2017. Rhino horn smuggled as jewellery. BBC News. Online 18 September 2017.

Grasso M. 2014. Cognitive Neuroscience and Animal Consciousness. In Bonicalzi S., Caffo L. & Sorgon M. (eds.); Naturalism and Constructivism in Metaethics. Cambridge Scholars Press. 182-203

Groves C. P., Fernando P., Robovsky´ J. 2010. The Sixth Rhino: A Taxonomic Re-Assessment of the Critically Endangered Northern White Rhinoceros. PLoS ONE 5(4)

Jones R. C. 2015. Animal rights is a social justice issue. Contemporary Justice Review 18(4): 467-482.

Moreto W., Gau J. M., Paoline E. A., Singh R., Belecky M., Long B. 2017. Occupational motivation and intergenerational linkages of rangers in Asia. Oryx. Cambridge University Press. U.K.

Mountain M. 2012. Scientists Declare: Nonhuman Animals Are Conscious. Earth in Transition. Online July 30, 2012.

Nuwer R. 2017. Asia’s Illegal Wildlife Trade Makes Tigers a Farm-to-Table Meal. The New York Times. Online 05 June 2017.

Ong S. 2017. The Rich Men Who Drink Rhino Horns. The Atlantic. Online 7 June 2017.

Rademeyer J. 2017. The Shifting Dynamics of Rhino Horn Trafficking. Inter Press Service News Agency Online 21 September 2017.

Save the Rhino International (SRI) 2017. Domestic trade in rhino horn. Save the Rhino International, London. Online 8 October 2017

Save the Rhino International (SRI) 2017. Poaching statistics. Save the Rhino International, London. Online 05 September 2017

Walton G. 2017. Africa poaching now a war, task force warns. Physorg. Online 23 September 2017.

WWF 2017. South Africa is still losing three rhinos a day. WWF South Africa. Online 27 February 2017

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()