sinuous, amphibious mammals

“Underwater eyes, an eel’s

Oil of water body, neither fish nor beast is the otter:

Four-legged yet water-gifted, to outfish fish;

With webbed feet and long ruddering tail

And a round head like an old tomcat.” ~ Ted Hughes, An Otter

![]()

There is something unaccountably beguiling about otters. Perhaps, as Ted Hughes wrote, it is their duality: a creature equally at home on land or in the rivers and oceans of the world. Or maybe it is the coiled tension in their sinuous bodies, which melt, sleek and powerful, into the water. Like their cousins worldwide, the otters of Africa have lively eyes, expressive features and utterly adorable squeaks, which have gone a long way to securing literary and internet fame.

Otters are intelligent and fascinating predators with an irresistible propensity for play. In Africa, this appeal is complemented by a sense of the mysterious – otter sightings are brief, infrequent and treasured by those fortunate enough to catch a glimpse of these extraordinary, amphibious mammals.

The musky mustelids

There are 13 recognised otter species, four of which are found in Africa. They belong to the mustelid family – the largest family within the order Carnivora and one of the oldest and most diverse. Other mustelids include weasels, badgers, wolverines and honey badgers. Almost all mustelids share a similar morphological design, with long slender bodies, short legs, and thick fur. Most are fierce, little predators. Another characteristic held in common is that almost all mustelids possess anal glands which produce a pungent (and to the human nose, obscenely malodorous) secretion used in olfactory communication.

The otters of Africa are sometimes referred to as “fisi maji” in Swahili, which translates as “water hyena”. Though the initial similarities may seem somewhat obscure, this is a surprisingly apt description. Like hyenas, otters are fast-paced and efficient hunters, but they are also opportunistic carnivores with mighty jaws capable of cracking open even the hardest crustacean shells. Otters are also expert problem-solvers.

The largest of the 13 otter species is the sea otter, which is also the heaviest member of the mustelid family and an exception to most otter “rules”. Sea otters are the only entirely marine species and, as a result, do not return to land or occupy burrows. Survival on the open sea has also necessitated a more flexible social structure than most freshwater otter species. Those plying their trade in fresh water spend much of the time on land and use holts/couches (the official names for otter dens) underground or in dense vegetation. All the otters of Africa otters are freshwater dwelling, though most will happily venture into the sea.

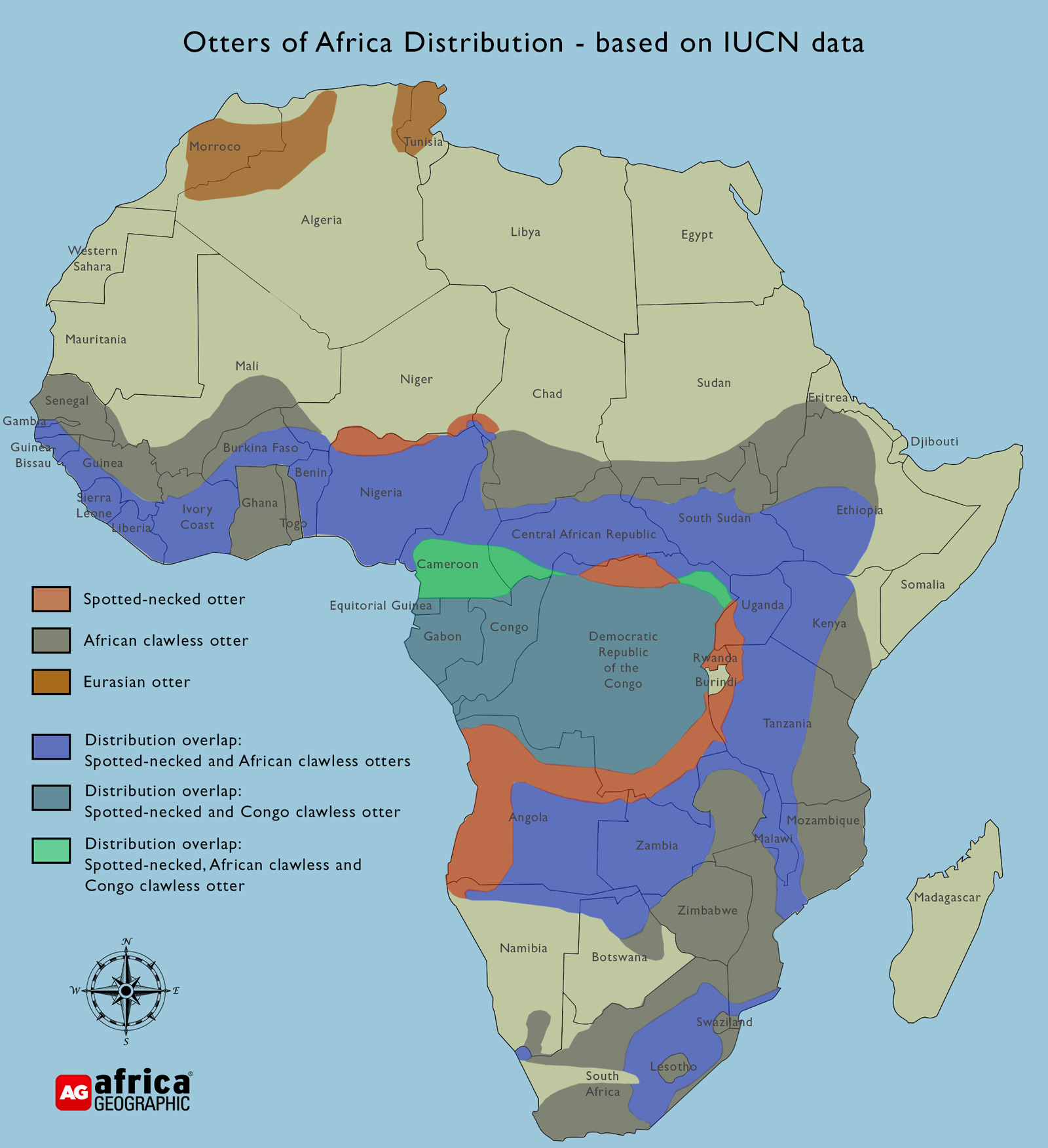

African clawless otter/Cape clawless otter (Aonyx capensis)

The African clawless otter is Africa’s most well-known and is widely distributed throughout most of sub-Saharan Africa (though they are most common in Southern Africa). As the second-largest freshwater otter species in the world, African clawless otters can reach over 1.5m in length and weigh up to 36kg (though the average is between 12 and 21kg). While not entirely clawless as their name suggests, their claws are significantly reduced, and their toes are only partially webbed, allowing for much greater dexterity.

Adaptable and resilient, African clawless otters can be found in various habitats, from dense forests to semi-arid savannas (provided there is a permanent body of water surrounded by sufficient vegetation). Though most are found in freshwater rivers and dams, African clawless otters will also readily enter the shallow ocean surf to hunt. They will also scavenge along beaches in search of crustaceans. Clawless otters are not picky eaters, and everything from fish and shellfish to amphibians and invertebrates are on the menu. Unlike the spotted-necked otter (discussed below), their thick whiskers allow them to hunt in murky water.

African clawless otters are primarily solitary but live within relatively tolerant family groups. Each individual occupies its range in a communal territory, marked by anal gland secretions, urine, and droppings (referred to as “spraints”). The females usually have between two and five pups, and the male plays no parental role.

Clawless otters are preyed upon by pythons, crocodiles and fish eagles in the wild, but habitat loss and water pollution are far greater threats. These factors have contributed to significant population declines over the last century. The IUCN currently lists African clawless otters as near-threatened.

Congo clawless otter (Aonyx congicus)

Fractionally smaller and slenderer than the African clawless otter, the Congo clawless otter was once believed to be a subspecies of the former (a matter that some zoologists still contest). As its species status is still relatively new (and their habitat comparatively tricky to traverse), this is probably the least researched or understood of the African otters.

They inhabit the swampy areas of the Congo Basin, and researchers believe that they are likely to be more terrestrial than other otter species. The agile fingers on the front feet are used to dig through the mud in search of molluscs and worms. Though little is known about their populations, the IUCN lists the Congo clawless otter as near-threatened.

Spotted-necked otter (Hydrictis maculicollis)

This tiny otter is considerably smaller than the two clawless species, though its distribution overlaps with both. Even the heaviest individuals seldom weigh more than 6kg. With their keen eyesight and webbed feet, spotted-necked otters are expert fish hunters, though they have been recorded eating crustaceans and amphibians as well. They are sight hunters and prefer deep, clear, flowing water.

The little white markings and spots on their chests are unique to each otter and can be used to identify individuals. They are also more sociable than the larger African otter species, though solitary when hunting. Spotted-necked otters manage their busy social lives through a wide range of vocal squeaks, and they are known to chatter merrily away during social encounters. The IUCN lists the spotted-necked otter as near-threatened

Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra)

The Eurasian otter, while highly elusive, has one of the widest distributions of any Palearctic mammal. These are probably the most well-known of all otters, yet few people realise that they occur in northern Africa (as well as across most of Europe and Asia).

Eurasian otters are strongly territorial and solitary, apart from mothers with young pups. Hunting and water pollution (particularly by pesticides) decimated otter numbers over the latter half of the 20th century. Increased restrictions have seen numbers recover in parts of their range, particularly in the United Kingdom. Their current population numbers in Africa are unknown and in urgent need of further research, according to the IUCN’s Otter Specialist Group. Overall, the species is listed as near threatened.

Pet pebbles and other otter oddities

Though tricky in itself to define, tool-use in the animal kingdom is often used to measure cognitive ability and subject to considerable research. Many animals use tools to varying degrees – including primates, elephants, cetaceans, birds, and, of course, otters. Sea otters are the most famous example – they use rocks to break open abalone shells and show a distinct preference for a specific rock suited to this purpose. These favoured rocks and pebbles are stored beneath a flap of skin in the otter’s armpit and are often kept for life.

Other otter species have been observed ‘juggling’ favourite rocks, displaying a considerable degree of dexterity and skill in the process (have a look here). The reasons behind this entertaining behaviour are a matter of considerable debate. It has been described as displacement behaviour (often observed in captive otters) or possibly as an indication of hunger-frustration. Whatever the biological reasons, this unusual behaviour comes across as playful and charming to the casual observer.

Pet otters

Unfortunately, there is an inevitable aspect to the charisma and charms of otters. “Celebrity” pet otters have seen a meteoric rise to fame on social media in recent years, and, inevitably, this has precipitated a demand in the pet trade (both legal and illegal). Worse still, “otter-petting cafés” have sprung up in parts of Asia, with the predictable associated welfare concerns. Though this trend has yet to affect African otters, the ever-increasing demand for exotic pets may well add the illegal pet trade to the list of threats facing otters in Africa.

Though exacerbated by social media in recent years, this is not a new phenomenon. Perhaps most famously, otters captured the heart and mind of Scottish naturalist Gavin Maxwell. However, the loving, playful character of Mij, the pet otter, described by the novel (and film) Ring of Brightwater, eclipsed a much darker tale. Edal, Maxwell’s female African clawless otter, was as famously misanthropic as the author himself and regularly attacked visitors. Edal once removed two fingers from one of her caretakers with one swift bite in a fit of understandable pique born of her captive frustration.

It should go without saying that otters do not make good pets. They are territorial and fierce, driven by wild instincts and possess strong jaws full of sharp teeth capable of biting through bone. These powerful and fascinating carnivores are designed to spend their days gliding through the waterways of the world, and it is in the wild that the otters of Africa are best appreciated.![]()

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()