Spear-wielding antelope

Heraldry, Renaissance artworks, animated films, cutesy toys, and the national animal of Scotland all bear testament to mankind’s appreciation of the mythical unicorn. Of course, most of us over the age of ten are aware that there are no horned horses in real life (a great disappointment to many). However, the ancient Greek scholars of natural history were entirely convinced of their existence. Ctesias describes them as fleet-footed wild asses, red, white, and black and sporting a one and a half cubit (around 70cm) horn. Aristotle took it one step further and described this particular creature as the unicorn’s ‘prototype’. He was, in fact, referring to the (admittedly two-horned) oryx.

While certainly not unicorns, there is something mythical about an oryx. Robust, dignified and courageous, the majestic sight of a spear-tipped oryx cresting a red dune, silhouetted against the setting sun, is iconic. In moments like these, this antelope is an embodiment of Africa’s desert spirit.

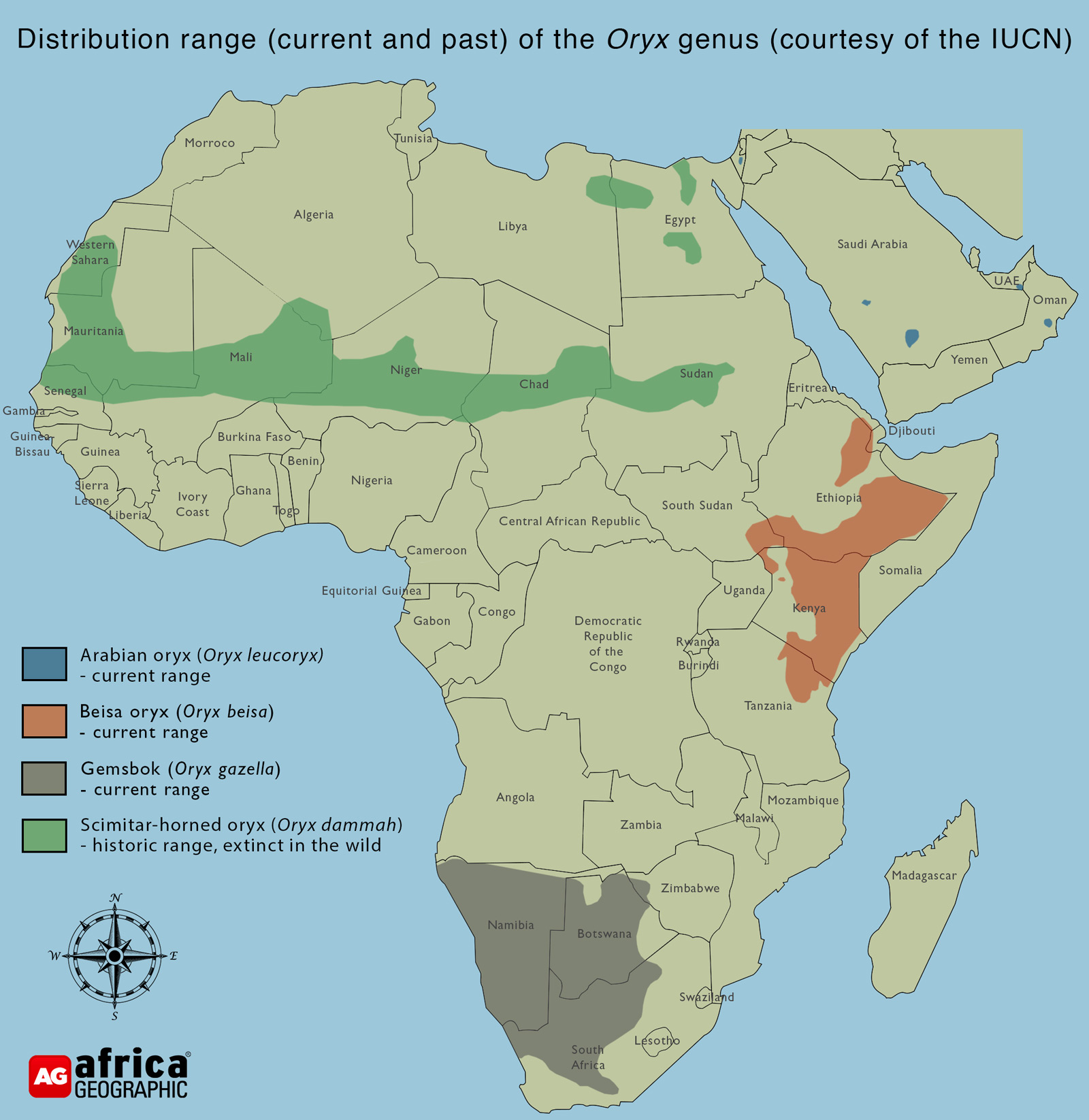

The Oryx family

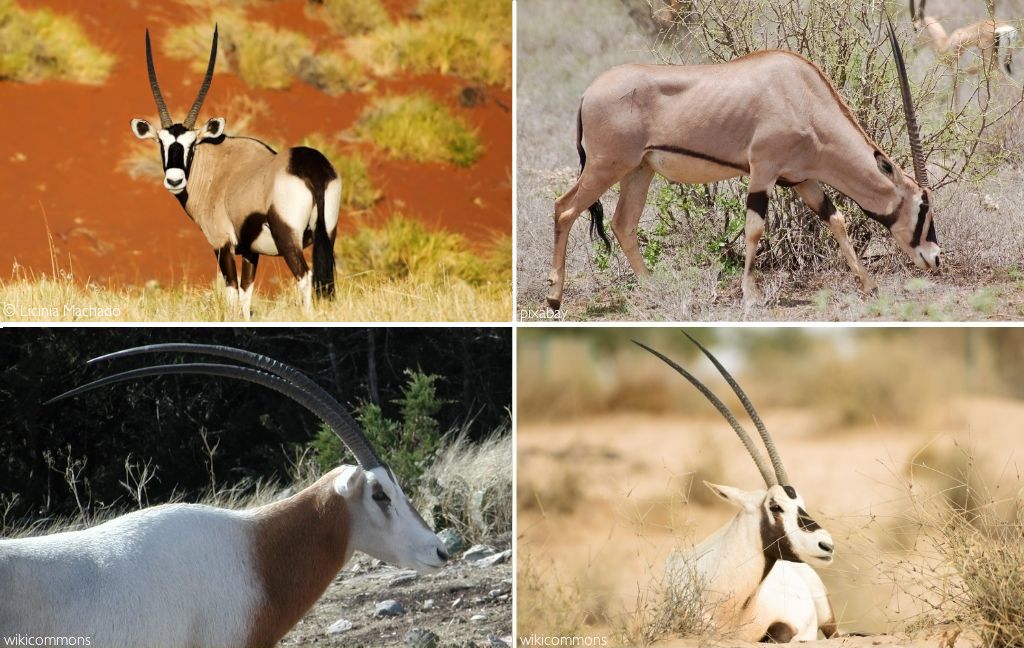

The oryx refers to four large antelope of the genus Oryx: the Arabian oryx (O. leucoryx), the scimitar-horned oryx (O. dammah), the Beisa oryx (O. beisa – also referred to as the East African oryx) and the gemsbok (O. gazella). All four are well-adapted to life in arid areas and can survive for several weeks without access to surface drinking water (more on this below). Black and white markings adorn the faces of all oryxes, but their coat colours vary from the white and cream of the Arabian and scimitar-horned oryxes to the tan of the almost identical Beisa oryx and gemsbok.

Another family trait is the formidable pair of horns that can reach over a metre in length. These sabre-like weapons are carried by both sexes and are used in battles for mating rights (or to ward off unwanted attention from enthusiastic males), and in defence from predators. Like other horned animals, oryx display exceptional proprioception when it comes to the tips of their horns. Even lions exhibit trepidation when tackling the scything weapons of a desperate gemsbok.

The Oryx genus is part of the larger Hippotraginae subfamily, also known as the grazing antelope. This subfamily includes the addax, as well as sable and roan antelopes.

Scimitar-horned oryx (O. dammah)

Like the Arabian oryx, the once widespread scimitar-horned oryx was hunted to extinction across North Africa, and they were officially declared extinct in the wild in 2000. They remain listed as ‘regionally extinct’ by the IUCN, as all populations in North Africa are fenced and managed such that they are not considered “wild” populations.

These striking antelope are almost entirely white, apart from their russet chests and necks. Unlike the other members of the oryx genus, the horns of the scimitar-horned oryx curve backwards towards their shoulders. Several captive populations are kept in research centres – most notably the Smithsonian National Zoo – so a fair amount of research into oryx morphological adaptations and social structure has been conducted on scimitar-horned oryx.

Beisa oryx (O. beisa)

The East African oryx was once considered a subspecies of the gemsbok, and the two species are physically very alike. However, genetic and morphological studies have proved their separate status. The Beisa oryx as a species is listed as ‘endangered’ by the IUCN.

There are two recognised subspecies of Beisa oryx. The common Beisa oryx (O. b. beisa) is found north of Kenya’s Tana River and into the Horn of Africa while the fringe-eared oryx (O. b. callotis) is distributed south of the Tana River and into parts of Tanzania. Both subspecies have been allocated their own IUCN classification, with the former considered ‘endangered’ and the latter ‘vulnerable’.

Arabian oryx (O. leucoryx)

In the early 1970s, the Arabian oryx was declared extinct in the wild. The wild populations in Oman, Saudi Arabia and the UAE today owe their existence to intensive reintroduction projects from zoos, breeding programmes and private collections. There are now an estimated 1,600 Arabian oryxes in the wild, and while they are still listed as ‘vulnerable’ by the IUCN, their population is considered stable.

The Arabian oryx is the smallest member of the Oryx genus, and the species name leucoryx refers to their almost luminously white coat.

Gemsbok (O. gazella)

Also known as the South African oryx (though its range extends across Namibia, Botswana and southern Angola), the gemsbok is the only oryx that is not vulnerable, endangered, or extinct in the wild. It is the largest species of the genus, with males standing about 1.2m at the shoulder and weighing up to 240kg.

As the most common of all the oryx, the information below relates to gemsbok unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Quick facts

| Social structure: | Herds of 10-40 animals, occasionally accompanied by a dominant bull |

| Mass: | 150-240kg (males heavier than females) |

| Shoulder height: | 1.2m |

| Gestation period: | 270 days (9 months) |

| Number of young: | 1 calf (twins extremely rare) |

| Average life expectancy: | around 18 years in the wild, longer in captivity |

The gemsbok is a large antelope, around the same size as a sable or roan and only fractionally shorter and lighter than a greater kudu. Their hooves are disproportionately large, and the two halves are flexible, preventing the antelope from sinking into the soft desert sand. They have been recorded reaching speeds of up to 60km/h.

They are highly nomadic, following rare seasonal rains and subsequent green flushes. Where drinking water is unavailable, gemsbok feeding habits become more selective. They target succulent plants such as tsamma melons and cucumbers and dig to access roots and bulbs.

Keeping a cool head in the face of great thirst

All oryx species are adapted to living in arid areas where daytime temperatures can easily exceed a sweltering 50˚C. A human exposed to such scorching weather would soon be awash with sweat in an involuntary physiological effort to cool down. However, the oryx does not have the luxury of wasting precious water on sweat unless absolutely necessary.

Instead of fighting a losing battle, oryx metabolisms are adapted to run at higher temperatures than most other mammals (something they have in common with camels and other desert-dwelling creatures). The internal temperatures of gemsbok have been recorded rising by over 4˚C during the day. Research conducted on scimitar-horned oryx showed that their body temperatures could increase to over 46˚C before they began to perspire. This is primarily due to the carotid rete – a network of blood vessels that essentially “trick” the brain’s hypothalamus into thinking the animal is cooler than it is.

Contrary to misconception, this selective brain cooling does not seem to protect the brain, nor is the brain more sensitive to rising temperatures than any other part of the body. (In fact, it is the digestive system that is most vulnerable to internal temperature changes.) Instead, selective brain cooling is a water conservation strategy. Many animals, including most of the artiodactyls (even-toed ungulates), have an operational carotid rete. Blood travelling from the carotid artery divides into fine blood vessels that run parallel to a network of veins carrying cooler blood from the oronasal passages. The arterial blood is cooled as it passes the cooler venous blood and then flows into the brain, cooling it slightly. The thermoreceptors in the hypothalamus typically respond to increased internal temperatures by triggering sweating and panting, which results in a loss of moisture due to evaporation. Even a small cooling effect on the receptors can conserve considerable amounts of body water. Thus, selective brain cooling is closely correlated to dehydration or lack of available water rather than external temperatures. This process is complex and is regulated by different physiological factors, including the salt concentration in body fluids.

In addition to the carotid rete, the kidneys of the oryx are specialised to reabsorb as much water as possible from the urine and oryx show greater water reabsorption levels from the colon. These methods, along with certain behavioural modifications (shade-seeking, for example) and specialised feeding, allow some oryx species to survive without drinking for up to 10 months at a time!

All’s fair in love and war

Gemsbok males are loosely territorial, and while fights are rare and generally short-lived, the horns are sharp and occasionally deadly at close range. However, a victorious male still has to face the ire of his intended mate, and female gemsbok are equally combative in their approach to love. Thus begins the “mating whirl around” phase of courtship as the female turns to meet her intended head-on, presenting him with a literal barrier of spears (and, from his perspective, the wrong end). Her eventual submission may well reward a persistent male, but only once he has proved his mettle in battle.

Nine months later, the cow moves away from her herd to give birth to a tan calf that initially looks nothing like the striking antelope it is destined to become. The tiny calf is highly camouflaged and will spend the first six weeks of its life in hiding, emerging only to suckle when its mother visits roughly twice a day. As the black facial markings and budding horns emerge, mother and calf reunite with the rest of the herd.

Enemies beware

Lions, cheetahs, spotted hyenas, and African painted wolves (wild dogs) all prey on gemsbok, though all do so with a considerable degree of caution. Renowned naturalist Jonathan Kingdon records instances of lions dying from gemsbok-inflicted wounds. Though the gemsbok will almost always flee if it has the choice, a trapped antelope will turn on the offensive, swaying, whirling, and stabbing at attackers with the grace of a fencing champion.

Conclusion

Whatever the Ancient Greek naturalists may have thought to the contrary, the oryx is about as far from a fairytale, horned pony with a penchant for maidens as conceivably possible. Instead, these mighty creatures with their fearsome horns and black warpaint markings exude an unmistakable “don’t mess with me” aura. This rugged design has allowed all four species to survive in some of the most inhospitable habitats on the planet. Yet for three of the four, it has done little to save them from a human fascination for their horns and pelts or from human-introduced diseases like rinderpest. Though the gemsbok is relatively common, the sad fact is that we have come disconcertingly close to losing the other three spear-tipped species.![]()

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()