Scientists have conducted one of the world’s first studies into the entire genome sequence of lions to reveal the evolutionary history of living and extinct lion species. They created a genomic dataset from DNA collected from 6 living lions from Africa and India, as well as 12 other historical specimens and two extinct Pleistocene cave lions.

The cave lion specimens originated in Siberia and Yukon and were previously dated as being around 30,000 years. The more modern lion specimens were sourced from between the 15th century right up until 1959. The genomes of four wild-born lions were sourced from Eastern and Southern Africa, and two came from the sole remaining Asian population. The study concluded that cave and modern lions shared an ancestor some 500,000 years ago and that the two main lineages of modern lions (Panthera leo leo and Panthera leo melanochaita) diverged some 70,000 years ago.

Once, the lion had one of the largest distribution ranges of any terrestrial mammal. The American lion (Panthera leo atrox), which stalked North America until around the Late Pleistocene (14,000 years ago), was the first of the “modern” lion species to go extinct, along with the cave lions (Panthera leo spelaea) of Eurasia, Alaska and Yukon. Modern lion species (Panthera leo leo) disappeared from southwestern Eurasia around the 19th to 20th centuries and, more recently, the Middle East. The Barbary and Cape lions disappeared in the middle of the 20th century. Surviving lions now occupy restricted ranges in sub-Saharan Africa and a small, isolated population of Asiatic lions in the Kathiawar Peninsula of Gujarat State in India.

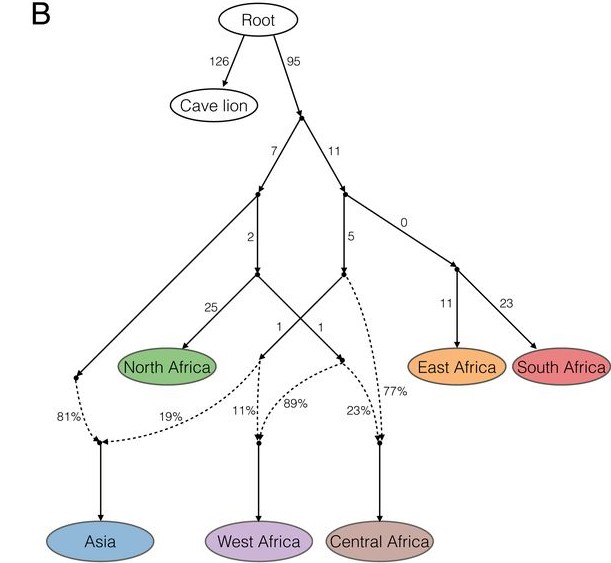

Previous work by the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group recognised two subspecies of modern lions. The first is the P. l. leo subspecies believed to have included the Asiatic lion, the extinct Barbary lion (thought to be related to Asiatic lions) and Central and West African lions. The second is the P. l melonchaita believed to include lion populations of East and Southern Africa, as well as the extinct Cape lion. The decisions of the task force were based on previous studies that analysed mitochondrial DNA.

However, the results of this genome-wide study produced different results. It seems as though Barbary lions (North African lions) were, in fact, more closely related to West African lions and that Central African lions should probably be grouped with the P. l. melonchaita subspecies. However, Central African lions were found to share more alleles with Asiatic lions than Eastern and Southern African populations do, and a Senegalese lion was also found to carry a large number of “southern” alleles. As an explanation for these mixed results, researchers suggest that West-Central Africa was a “melting pot of lion ancestries” where mixing may have occurred after the subspecies diverged. They emphasise that more study is necessary.

Interestingly, they were also able to infer that the P. l. leo subspecies (the northern lineage) went through a severe genetic bottleneck around the same time as the two subspecies diverged, suggesting that the northern lineage was populated by a few migrant individuals from the P. l. melonchaita (southern) lineage. An evaluation of more recent effects on the genetic diversity of both subspecies showed that lions of the northern lineage exhibit even less genetic diversity than those from the southern lineage. As a previous study has shown, humans are not always entirely to blame for a loss of genetic diversity, but in the case of the northern lineage of lions, anthropogenic pressures are likely to have had a significant impact. The tiny remaining population of Asian lions showed the least genetic diversity and scientists warn that this puts them at high risk of health issues due to inbreeding, including susceptibility to diseases.

While the researchers do acknowledge the need for further research, their research does have practical implications beyond historical interest. For example, they have shown that Barbary and Cape lions did not represent distinct groups or unique subspecies. In the case of efforts to restore populations of North African lion populations, those involved need to be aware that Barbary lions were more closely related to West African lions than Asian populations and so West African lions would be more appropriate as a “donor” species. Also, their results suggest that the subspecies classification of Central African lions may need further consideration. These distinctions may seem small, but they play an enormous role in fundamental policy decisions in determining the conservation status of an animal or where relocations/translocations programs are concerned. On a microscope level, complete genome maps can be translated as a history of species, but on a macroscopic level, they translate into crucial conservation policies.

Read the full study here: “The evolutionary history of extinct and living lions”, de Manuel, M., Barnett, R., et al, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA (2020).

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()