What rural Batswana feel about elephants – beyond politics and ideologies

SO, WHAT’S IT LIKE LIVING AMONGST ELEPHANTS?

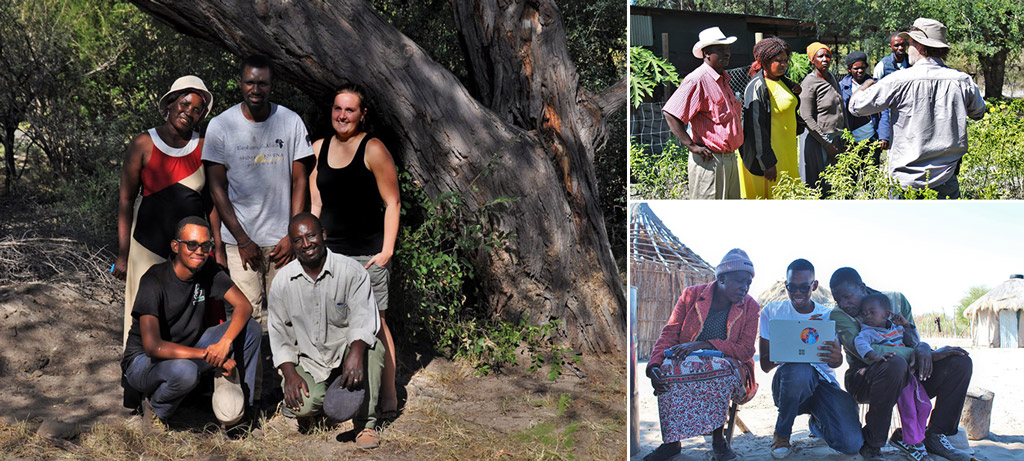

I wanted to find out for myself. The debate has been heated since the Botswana government decided to resume trophy hunting and other elephant control measures. Competing vested interest groups all claim the moral and factual high ground, and the elephants have become political collateral in the process. I found myself confused, frustrated and conflicted by the dominance of binary ideologies in these debates. During this trip to Botswana, I wanted to go beyond the angry rhetoric, and focus exclusively on the most important humans in this ongoing drama – those that live amongst elephants.

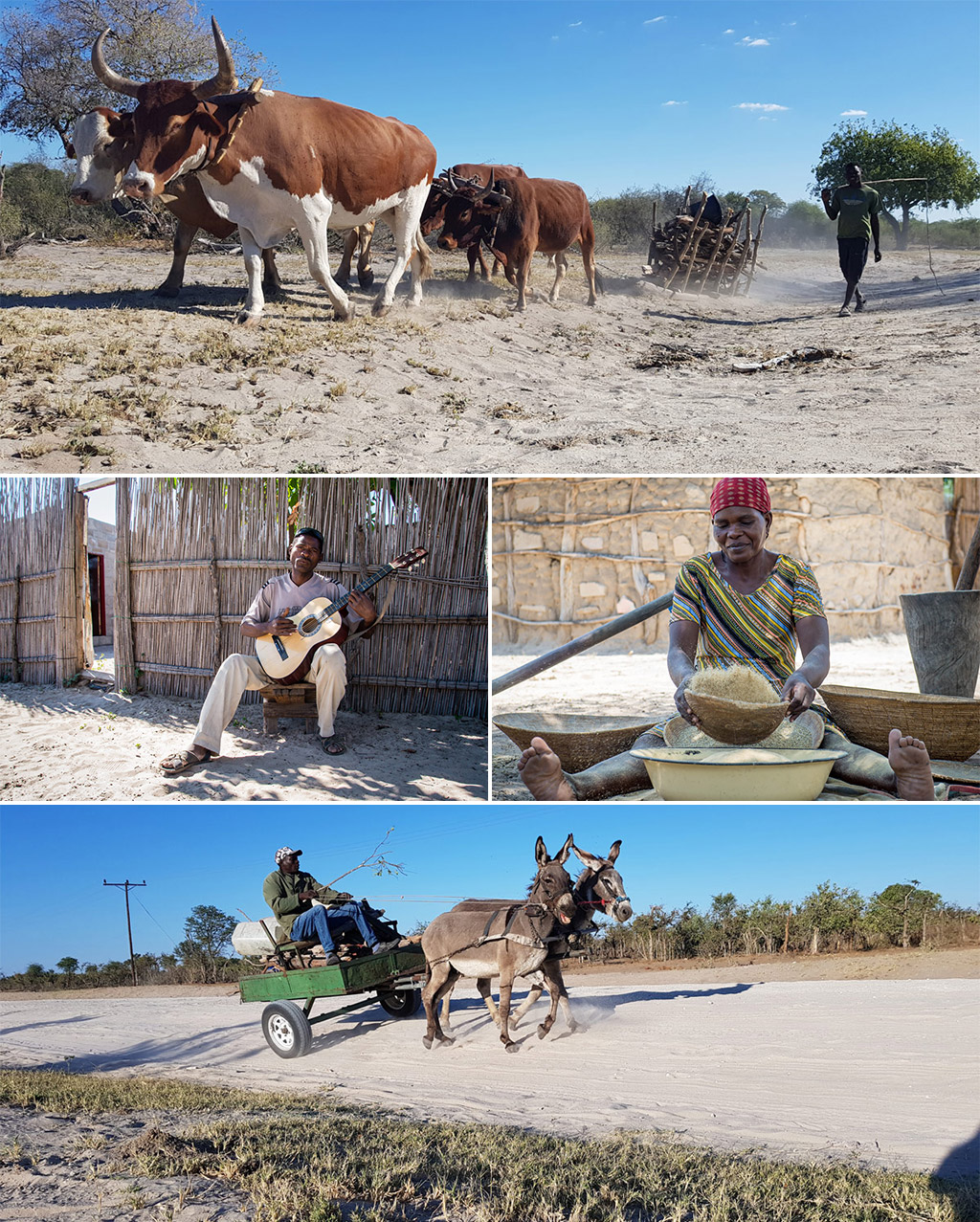

My travels saw me based in two communities suffering under significant ongoing human-elephant conflict – one being the eastern Panhandle area immediately north of the Okavango Delta, and the other being on the banks of the Boteti River, bordering Makgadikgadi Pans National Park. I chose not to visit that other area of major human-elephant conflict, Chobe’s Kasane area, because of the focus of mainstream media on that area, and my perception that the area is highly politicised.

First though, here are five critical pointers that came through clearly from the approximately 40 people that I spoke with during this mission. This was not a scientific survey, and I emphasise the local and anecdotal nature of my encounters. My hosts arranged some of the discussions, and others occurred during ad-hoc encounters. My approach to each discussion was to prompt a debate about elephants and listen.

1. None of the citizens I spoke to appeared to harbour hatred or resentment towards elephants – although there was an underlying sense of frustration and in some a fear of elephants. This does not imply that there is no anger out there, but it does provide an alternative lens to some of the talking heads unearthed by news media and vested interest groups;

2. All of the citizens I spoke to felt that there are currently too many elephants in their community and surrounds. None wanted elephants to be obliterated, but most wanted elephants reduced in number;

3. Without exception, citizens that I spoke to recall that elephants were rarely, if ever, encountered in their neighbourhood in the comparatively recent past, and that there were few human/elephant conflict issues back then. Elephant numbers started increasing in the mid-1990s in the Panhandle area, and after 2010 in the Boteti River area – keep reading to find out why. They stressed that they are learning how to live with these new arrivals to their neighbourhoods;

4. Trophy hunting was not viewed by those that I spoke to as a solution for their elephant-related problems. Many had no recollection of ever having benefited in any way from historical trophy hunting operations, but some expressed hope that the reintroduction of trophy hunting would provide some benefit to them in the future;

5. Attacks by elephants on people happen regularly, and below I will tell you about my meeting with a survivor of one such attack. There have been numerous recent reported incidents of rural Batswana being killed by elephants, and shortly before my visit to the Panhandle area, a 4-year-old boy from a village called Beetsha was killed by an elephant while out with his father, who was herding his livestock. I cannot even imagine the anguish his family must feel, and the resultant emotional scarring for the entire community. The boy’s name was Kefeletswe Barelelwang.

PANHANDLE

It was my first evening in the Eastern Panhandle area, and Graham McCulloch from The Ecoexist Project and I were staking out an elephant corridor on the well-used dirt road between Seronga and several small villages towards the east. Before long, a breeding herd of about 200 elephants scurried across the road in the dying light – a tightly-bunched herd of all ages moving fast in the dust cloud, with curled tails and rolling eyes. “Imagine being caught in that frightening avalanche” I muttered, as the elephants eventually disappeared into the treeline south of us. “Indeed,” agreed Graham, “and this is the norm for the many people that use this road to get to school, the shops, or work. Elephants are continuously moving across this road from March to when the rains arrive in October or November, between the dry deciduous woodlands to the north and the Okavango Delta to the south. As they follow timeworn migratory routes, they have to negotiate paths between fields and settlements, and cross this busy road”.

Along the way, these elephants snack on crops, with devastating consequences for these subsistence farmers with no other means of earning a living. Data from Ecoexist director Anna Songhurst’s PhD research reveals that ploughing fields less than 1km from an elephant pathway are twice as likely to be raided by elephants. This and other data extracted from 40 collared elephants are used to develop strategies to minimise elephant-human conflict, and new farming techniques are taught, to help farmers increase their yields.

Graham continues: “The incidents of elephant conflict with humans in these areas are high, and they are scared, nervous and sometimes irritable when they pass through – these are ‘fear zones’ for elephants. But, unlike the situation in poaching and trophy hunting fear zones which elephants stay away from, here they keep on crop-raiding – possibly because the risk-return equation is comparatively lower, but also because of the need to access critical resources. Elephants can be legally killed if caught in the act of crop-raiding, and of course, if they attack humans. Currently, about 20 elephants per annum are killed in this area, as problem animals.”

Just minutes before the herd scurried across the road, we had given a lift at this specific location to two young girls that were walking to school after a weekend at home. What if they were there when the elephants crossed, I wondered?

Makhata’ Max’ Baitseng, a senior team member of Ecoexist, later explained that this block of about 8,500 km2 in northern Botswana is ideal elephant habitat, in that it includes nutritious woodland to the north of the road and water, fruits and grass to the south. Elephants are not alone here though, humans also inhabit this land, and the humans are concentrated in a narrow band of villages to the south of the block – bordering the watery Okavango Delta. The estimated 16,000 human inhabitants share this space with an estimated 18,000 elephants (the estimated elephant population in 2008 was 8,905). To provide context to this density of elephants, the 20,000 km2 Kruger National Park is home to about 21,000 elephants, and there are no indigenous communities in the park.

This influx of elephants after the mid-1990s is likely due to poaching pressure in Angola, Namibia and Zambia, although Graham surmises that the elephants are also breeding well here, thanks to favourable conditions. He mentioned that the upward elephant population curve would probably flatten out when the current drought sets in, with young elephants dying first. This is a natural process that must be allowed to occur in a healthy population such as this. But, he cautioned that incidents of human/elephant conflict would surely increase even further as competition for water and food intensifies during the drought.

Graham also explained that elephant carrying capacity in a shared landscape is all about social AND ecosystem thresholds. He continued: “We all need to recalibrate our perspectives and understand that these people are successfully living with elephants, which compete with them for water, food and space, but that this existence is a hard one. We need to develop ways to keep people and elephants safe, mitigate incidents when they do happen, and provide an incentive for people to continue tolerating the threat to lives and livelihoods and to benefit in some way from the presence of elephants. If we do not do these things, then these areas will go the way that much of the ‘developed’ world has gone – where animals perceived by people as being dangerous are extirpated and where ecosystems are tamed and utilised for farming and recreation.”

Meet subsistence farmer Kunyima Ramosimane, who has been farming since 1988. Her tshimo (ploughing field) is 6 km from her hometown of Gunotsoga, and she walks between the two – along a path that leads through mopane woodland with elephant tracks everywhere. Every year in about November (when the rains start) she plants her crop – including millet, sorghum, beans, groundnuts and watermelons. Before the influx of elephants in the mid-1990s, she used to visit and tend the crop every week or so, but these days she has to sleep at the field throughout January till the harvest in April and May, to try to keep the elephants away. When the elephants arrive, often at night, she shouts and bangs a pot to try to scare them away. She is now scared of elephants because they often react aggressively when she tries to scare them away from her fields, and when she encounters them while walking in the area to forage for wood and bush fruit. This year the elephants arrived early (possibly due to the drought) and ate her entire annual crop. In a good year, she harvests enough food for her family and sells any surplus to buy clothes and pay for school fees for her son Steven. This year, she does not know how she will get by until the next harvest. She has applied to the government for compensation but has received nothing for the past three years. I was subsequently advised that government coffers have run dry, due to the escalation of compensation claims. As if life was not tough enough, Mma Kunyima’s chickens are dying from an unknown ailment.

Subsistence farmer John Mbango also lost his entire crop this year – to the drought. This long-time Gunotsoga resident told me that trophy hunting in this area was stopped in 2008 (the country-wide suspension was imposed in 2014), due to repeated bad behaviour by the professional hunters that operated the concession. He said that the tourism lodges now operating in those community areas bordering the Okavango Delta provide more permanent jobs compared to the seasonal hunting jobs, but that as a farmer he does not benefit directly from tourism. He also did not receive any direct benefits from trophy hunting at the time – pointing out that the carcasses were left far away, in remote areas, and so the meat was not accessible to people from the village. When I asked him how trophy hunting could help him and other local farmers, he said that the money needs to be enough, and go directly towards securing all ploughing fields in the area against elephants, using solar-powered electric fences.

I also met with a group of subsistence farmers in the area, and their message was similar to others – the elephants are the new arrivals, and they wanted there to be fewer of them. They had all lost their crops this year – to a blend of drought and elephants. When asked about whether elephants are damaging large trees in the area, they confirmed that elephants were now targeting previously untouched neighbourhood trees like jackalberries and baobabs. They mentioned that elephants kill cattle once or twice a year when they compete for water and when the cattle sleep at night under camelthorn trees which elephants target for the nutritious pods. There seemed to be no grasp amongst this group of how trophy hunting could help them, or why it was seen as a solution for their problems with elephants. One wizened gentleman said that there is no system in place for trophy hunting benefits to flow down to them.

Later that day, Graham and I were staking out an area of ploughing fields often visited by elephants. In the dying light, he explained that Ecoexist has been assisting the government to reduce conflict by consolidating ploughing fields together, called ‘cluster fields’, and taking advantage of economies of scale to erect solar-powered electric fencing and boreholes. He explained how the corridors are critical in forming part of a holistic, landscape approach that includes space to allow elephants to move through field areas and these ‘cluster fences’ that more effectively protect field areas. The method has been working so far, but this route will require significant funding and management, and changing of generations of traditional farming practices to more sustainable ones. During this time of twilight contemplation, my mind drifted to the efforts by lodges bordering Hwange National Park, which face similar issues, and who embrace the challenges via conservation safaris.

During my last morning in the Panhandle area, I attended a wonderful community-run village tour called “Life With Elephants”, facilitated by Ecoexist director Amanda Stronza, which focuses on educating tourists about living with elephants. A few lodges already send clients for this valuable exposure to real village life, including an ultra-luxury lodge whose guests arrive by helicopter! Guests get to visit a ploughing field, the local iron monger and operate the manual village water pump which was installed to reduce the need to compete with elephants at the river. They also pass by a large fallen baobab tree around which the ancestors gather at night to discuss village matters in whispered conversations. The baobab fell in 2000 (without any assistance from elephants) and still lives.

My favourite part of the tour was story-telling and music in the shade of an enormous rosewood (false mopane) tree. Born in Eretsha in 1942, Daniel Senwametsi tells how he regularly used to walk to Namibia in bare feet and how he used to wear animal skins until a stint of working in the South African mines meant he could afford to buy clothes for himself and his family. He remembers seeing very few elephants before 1996, after which poaching in Angola saw them fleeing to the safety of his neighbourhood. He also worked at a luxury lodge for many years before becoming a subsistence farmer in 2004. Daniel gave a demonstration of how to behave when attacked by an elephant, a replay of when he was attacked while walking to his fields. His enthusiastic and animated demo had us all in stitches :-). This finale of a wonderful tour takes place on the shore of what would normally at this time of year be a floodwater plain, but this year it is bone-dry because of low rains in the Angolan highlands headwaters. Daniel told me that this is the first year in his entire life of no floodwater at this time of year. The ‘Life with Elephants’ tour is an example of the kinds of elephant-related enterprises that Ecoexist is facilitating that need to be promoted more to provide support and benefits to people who live with elephants.

During my stay in the Panhandle area, I spent my sleeping hours at a rustic community-owned guesthouse called Sausage Tree Lodge (no known website or Facebook page) in the village of Eretsha, with meals at the nearby Ecoexist base camp.

BOTETI

TO BE ATTACKED BY AN ELEPHANT

So, what’s it like to be attacked by 5-6 tons of fury, an animal capable of pushing over huge trees and casually flipping cars?

One sobering meeting for me was with a subsistence farmer who is convalescing after recently being attacked by a bull elephant. She was collecting firewood near her home town of Khumaga (Xhumaga) on the bank of the Boteti River, bordering Makgadikgadi Pans National Park. The attack was unprovoked, and the furious elephant only relented after its inert victim was covered in dust and obscured by a bush. I spent time with this dignified lady and her husband in their neat home in Khumaga, and heard her story firsthand. Her broken leg was still in plaster, and she was in obvious discomfort and pain. She did not want to be photographed or named. She is now terrified of elephants and does not see how humans and elephants can co-exist. My lasting memory of her is her brave smile and apparent determination to move on from what must surely have been a terrifying ordeal.

I spent time in this particular elephant conflict zone with community outreach officer Walona Sehularo and research assistant Thatayaone Motsentwa (TT) of Elephants for Africa, and was based at their research camp on community land on the banks of the Boteti River.

Walona explained that the problem-causing elephants in this area are usually bulls, which comprise 98% of their research sightings. Again, based on current memory, elephants only arrived in the village area comparatively recently – after 2010 when the Boteti River flowed again after a 20-year hiatus of no floodwater from Angola. Before then, male elephants were seen in the national park, but seldom in the neighbourhood community land. Again, local people now have to learn how to live with elephants. Walona went on to explain that many local people tend to view wild animals as belonging to the government and that they expect the government to control them, as farmers have to control their livestock.

This region has its own unique dynamic. Because of the regular human/elephant conflict, the government undertook to erect a new fence between the national park and the community. The fence would cut the community off from the water of the Boteti River, except for access via small pedestrian gates, and so the plan was to provide piped water. Community members with farming plots on the river bank have been advised that they will have to move their subsistence farming operations into the sandy hinterland. River plots are highly sought-after because they offer two plantings per annum – one before the rainy season of November to March and the other before the annual floodwaters from the Angolan highlands arrive from June to August. These government plans have stalled for a few years, and the locals are restless. There is in fact already a double fence line that crisscrosses the river – one being the veterinary fence that separates cattle from wildlife to abide by European beef export rules.

But both fences are mostly broken or partially removed by the authorities, with wildlife and livestock passing freely between the national park and community land. I sat at the research camp and watched livestock come and go from the national park, and elephants cross in the twilight hours to forage on community land. During one extended drive into the national park, I saw many goats and cattle a few kilometres inside the park.

Walona and I managed to secure a meeting with the chief of Khumaga, Kgosi Keeditse Orapeleng during a kgotla (village meeting). This respected gentleman explained via Walona as an interpreter that he and his people feel a strong connection with elephants. But, he added, life with elephants is tough, now that there are so many of them. He recalls that before the elephants arrived, life was better, and he hoped that the new fence would solve the problems caused by elephants. He also mentioned that lions also used to be a problem historically when they came from the national park to kill livestock until trophy hunters exterminated them many years ago.

Meet Clifford Tekanyetso – the son of Gakeitseope, a former tourism lodge guide and now farmer, who is being helped with elephant issues by Elephants for Africa. He and his father live in Khumaga, but sleep in a tiny hut on the family field whenever there are crops to look after and protect. Clifford proudly showed me his family field, which is secured by a solar-powered electric fence – a local success story. Clifford explained that they do not lose crops to elephants anymore, although vigilance is still required – just last week Clifford had to chase away an elephant that broke through the fence. In addition to an annual crop of beans, watermelons, maize, millet and sorghum, they grow a summer legume known as ‘lablab’ that is dried for supplementary livestock fodder during the dry winter months.

One meeting that left a strong impression on me was with 60-year-old farmer Gofentsemang Johane, who has two ploughing fields – one in the dry sandy woodland and one on the bank of the Boteti River (she will lose this field in terms of the new fence plan). This determined lady has seen many growing seasons and faced many challenges in addition to the recent increase in elephant presence, and her stoic approach impressed me. She also collaborates with Elephants for Africa and has a solar-powered electrified fence that keeps her crops safe from elephants. She burns ‘chilli bricks’ to keep elephants away. Chilli is mixed into balls with dry elephant dung, which smoulders when heated coals are placed on top – elephants do not like the pungent smoke.

Despite these measures, Gofentsemang is too afraid to sleep at her fields because of the elephants that come at night. At one stage during our chat, she fixed me with a quizzical eye and asked: “So, how will your story benefit me? Maybe it will change people’s perceptions, but here and now I really need a water pump, to increase my production from one to two harvests per year. That will make a real difference for my family and me. Will your story help me?”

That, dear readers, is up to you. How you react to my personal experiences with these real people depends on your ability to see the wood for the trees.

This is a story of hope, of people who are sharing their home with elephants and other wildlife.

How does this perspective differ from your home context? Do your children face life-threatening animals on the way to school, or could wild animals eat your entire annual food supply in one raid? Perhaps those threats to lives and livelihoods were removed from your society long before your time, and you cannot recalibrate your perspectives to appreciate the reality for these people in Botswana. Whatever your situation, these rural villagers ARE living with elephants to the best of their ability, and for that, they deserve our respect. They certainly need our willingness to try to understand their daily struggles, and to change the debate from acrimonious finger-pointing and threats of tourism boycotts, to finding real solutions for real problems. So that they can continue living with the largest concentrations of elephants in the world.

Keep the passion

~ Simon Espley, CEO

ABOUT ECOEXIST

Ecoexist operates in the Eastern Panhandle area of northern Botswana to reduce conflict and foster coexistence between elephants and people. The team finds and facilitates solutions that work for both species, by combining science with practice. Its mission is to support the lives and livelihoods of people who share space with elephants while considering the needs of elephants and their habitats. Ecoexist works in close partnership with the Botswana Governments’ Department of Wildlife and National Parks and Department of Crop Production, as well as the communities of the Eastern Panhandle. Its supporters include The Howard G. Buffett Foundation, The GoodPlanet Foundation, USAID/WWF Namibia, USAID SAREP, and The Amarula Trust.

ABOUT ELEPHANTS FOR AFRICA

Elephants for Africa works towards human-wildlife coexistence in community land bordering the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park of Botswana. They take a holistic approach to human-elephant competition by understanding the social and ecological requirements of both humans and male elephants. Partnering with the communities bordering the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park and working closely with the Botswana government’s Department of Wildlife and National Parks to ensure their work addresses the needs and concerns of local and national stakeholders. Their education programs focus on developing the conservation leaders of the future and empowering local communities. Its funders include GoodPlanet Foundation, the International Elephant Foundation, The Columbus Zoo Fund for Conservation, The Memphis Zoo and Jacksonville Zoo.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, SIMON ESPLEY

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in South Africa with his wife Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()