A recent survey by Space for Giants in South Sudan shows that one of the largest mammal migrations on earth, the white-eared kob and tiang migration, continues, apparently oblivious to the decades-long civil conflict. Numbers are sketchy for obvious reasons, but white-eared kob, tiang (a close relative of the topi) and a smattering of Mongalla gazelles (possibly a subspecies of the Thomson’s gazelle) continue their annual migrations.

South Sudan is a large country – one and a half times the size of South Africa. It is also a country that has seen horrific, long-standing conflicts. The First Sudanese Civil War dragged from 1955 until 1972. The Second (essentially a continuation of the first) went from 1985 to 2005 and resulted in independence for South Sudan (previously controlled by Khartoum in the north). A multi-sided South Sudanese Civil War then kicked off in 2013 and only really ended in February 2020.

Migration overview

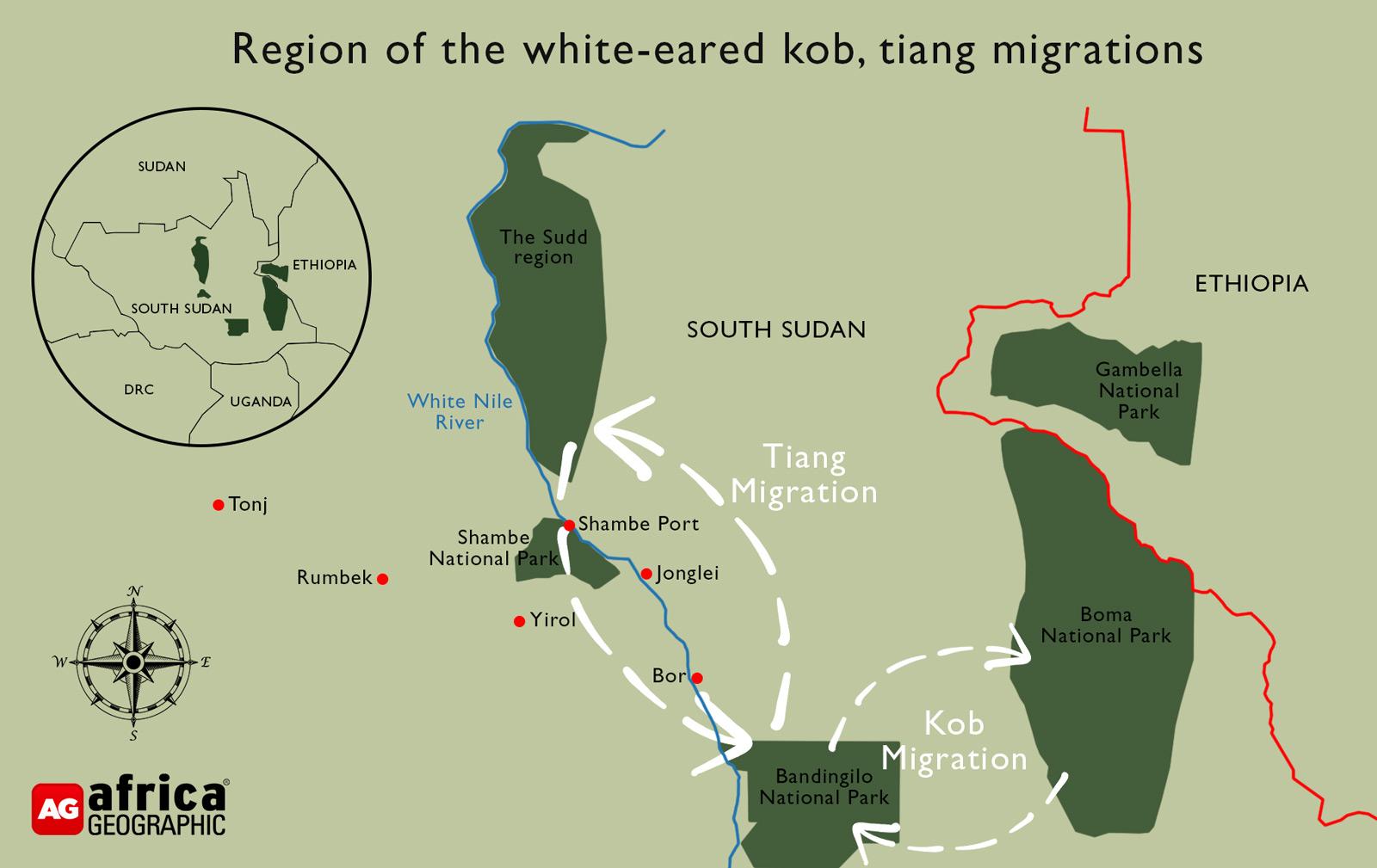

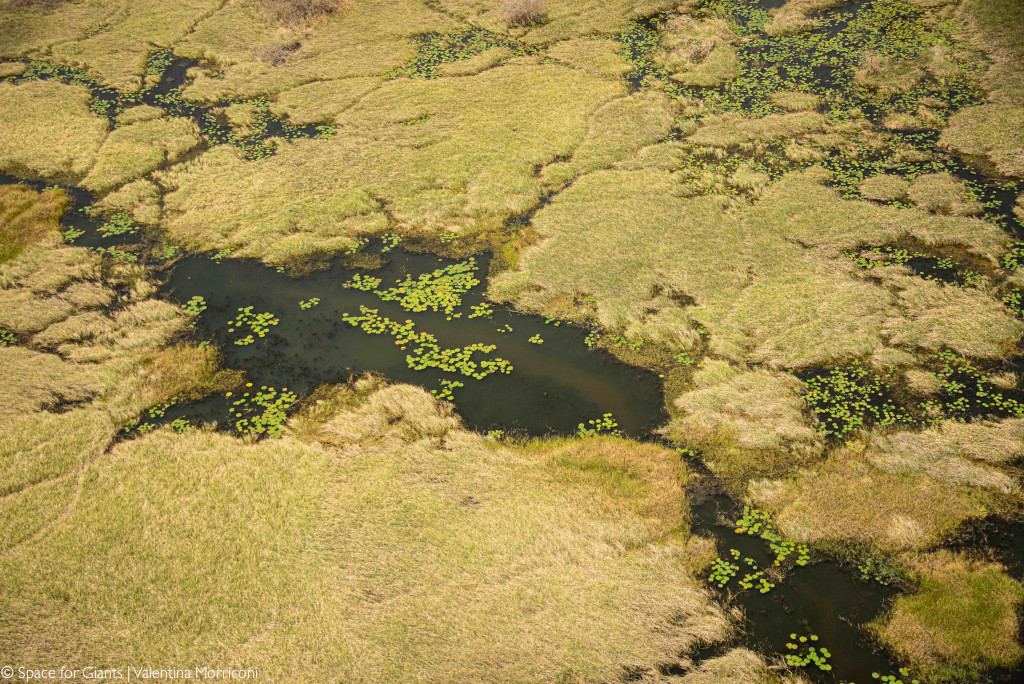

Between January and June, the kob, tiang and gazelle move north and east from the wetlands on the eastern bank of the White Nile towards Boma National Park and Gambella National Park just across the border in Ethiopia. They return to Boma National Park and the vast inland delta known as the Sudd between November and January. The delta is the biggest in Africa and, in the wet season, may extend to 130,000 square km. It is home to 400 bird species and, in addition to the kob, tiang and gazelle is a refuge for the endangered Nile lechwe. Fifty years ago, there were 80,000 elephants in the region; now, there are probably fewer than 2,000.

With all the civil war, conservationists have been unable to monitor the extent of the herds or the effects of the conflict. Soldiers killed masses of bushmeat to supply the war effort while ivory was exported from the region via Juba. The war for independence saw the local extinction of zebras and rhinos, once abundant in the southern areas.

Hope

In March 2021, Dr Max Graham, founder and CEO of the international conservation organisation Space for Giants, led a rapid conservation reconnaissance survey of a selection of South Sudan’s protected areas. The goal was to understand the country’s wildlife better and explore options to support the government with its conservation work and, eventually, attract conservation tourism investors. The five-person team logged 33 hours of aerial surveys from a low-flying helicopter, travelling across Rumbek, Tonj, Yirol. Shambe National Park, Shambe Port and The Sudd, Jonglei, Bor and Boma National Park.

A key area of their focus was the status, following South Sudan’s most recent civil war, of the world’s second-greatest large mammal migration of tiang and white-eared kob.

Dr Graham talked to Africa Geographic about the survey mission and its findings.

Can you give us some broad findings from the recce?

There was a paucity of large wild animals in the areas we visited in and around Shambe National Park, west of the Nile, except for aquatic or semi-aquatic species, including sitatunga, Nile lechwe, hippos, and Nile crocodiles. Reedbuck, bushbuck, and duikers were seen but were uncommon. We saw indirect evidence of elephants and buffalo from old spoor around watering holes and came across a significant population of roan antelope west and north of Shambe.

Clearly, the elephant population here is under extreme hunting pressure given their local scarcity and the ubiquitous presence of ivory bangles among local herders. I think it could also be said with some confidence that the possibility of the Shambe area holding any remnant population of northern white rhino is extremely low given the large number of armed individuals, including specialist local hunters, and the territorial ecology of rhinos.

The area to the immediate east of the massive, abandoned, German-built machine designed to dig the Jonglei Canal was abundant in wildlife at the time of our recce with large populations of tiang, lechwe, white-eared kob and Bohor reedbuck. (The abandoned Jonglei canal project aimed to divert water from the Sudd to deliver more water downstream for agriculture in Sudan and Egypt). There was very little evidence of people in this area, east of the Nile, and it is clearly a stronghold for wildlife. Subsequent discussions with key informants suggest this area may be a no man’s land between conflicting ethnic groups, creating a haven for wildlife. As we travelled south towards Bor, wildlife began to disappear in the face of human presence, charcoal burning and deforestation.

Boma National Park and its immediate vicinity held the bulk of white-eared kob seen on this reconnaissance survey. We observed them in their tens of thousands, with smaller but significant populations of tiang. A small group of just four giraffes and around twelve eland were also observed. Both groups were highly nervous and it is clear they were under intense hunting pressure. We observed armed people throughout the park.

How have the numbers of migrating animals changed with the civil war?

After the wildebeest migration of the Mara-Serengeti ecosystem, these herds of white-eared kob, tiang, and associated other species, are the largest concentrations of large mammals left on the planet. That this is one of the wonders of the world is indisputable. That it has survived the long, persistent, armed conflict within South Sudan is testament to how little development there is in the country and the inaccessibility of the seasonally water-logged flood plains east of the Nile and into Ethiopia.

Research led by South Sudanese wildlife ecologist Dr Malik Morjan and supported by the Wildlife Conservation Society found that white-eared kob numbers were not dramatically affected by the 1985-2005 South Sudanese Liberation War. However, tiang were affected, with numbers estimated to have dropped from 500,000 to 160,000, mainly due to hunting by the armed forces at the time. This may be because the tiang dry season range is closer to the conflict. It isn’t clear what has happened to Mongalla gazelles which were counted at around 66,000 in the 1980s but could actually number many more today.

It also isn’t clear how the recent civil war, from 2013 to 2020, has affected overall numbers of all of these species, as we could not undertake a complete aerial survey during our recce. What surprised us was the numbers of tiang we came across to the north of their dry season range, near the Jonglei canal. Given the absence of human settlement here, possibly due to insecurity created by the civil war, we wonder if the tiang might have recovered from the negative impacts of the Jonglei canal construction, which began in 1978 but stopped at the opening of the 1985 war and never restarted.

We were also struck by the number of hunters and scattered settlements in and around Boma and Bandingilo National Parks and the clear evidence of hunting evidenced by the many animal carcasses. When we did come across kob in large numbers in parts of Boma National Park, there were always people in relatively close proximity, suggesting they may be under pressure, despite their large numbers.

I would tentatively suggest that white-eared kob may have been worse affected by hunting in and around the national parks in the Boma-Jonglei ecosystem than tiang, which used a different part of the range, towards the Sudd swamp, during the recent civil war. This would need to be verified through a complete aerial survey.

How much pressure is there in the Boma and Bandingilo corridor?

What is important to note is that most of the kob and tiang migration actually falls outside of the two protected areas so it is not so much a ‘corridor’ as an entire 200,000 square km ecosystem, stretching from the Sudd and White Nile in the north-west, to Boma National Park and the Ethiopian border in the south and east. The animals move across this whole landscape seasonally. Currently, the only pressure on the corridor is hunting by local people and armed forces. This may have been amplified during the recent civil war because of the lack of alternative food sources.

The medium-term pressure is, however, far more significant. According to research led by Dr Morjan before the recent civil war, 72% of the known kob migration, and more than 99% of the tiang migration, fall within leased oil concessions. With the country desperate to exploit the benefits of oil revenue, the associated infrastructure development that might emerge could be devastating for the migration. For example, three of the ten priority roads planned by the government cut through the migration. Furthermore, South Sudan has a high population growth rate, and settlements within the ecosystems could soon become urban centres.

Has the migration route changed with human encroachment and settlement?

It appears from our recce survey that the distribution of ungulates was similar to that found in previous dry seasons, if not a little more extensive in the north than described previously. It is important to note just how big this migration is. Kob have been recorded moving across 68,805 square km and tiang across 35,992 square km, both sparsely populated by people. However, there appears to be growing pressure on the kob in the southern part of their range due to increasing human settlement and possibly an increase in hunting.

How secure are Boma and Bandingilo from human encroachment?

Both have significant, growing human settlements within and outside the parks, accommodating traditional villages that existed before the parks’ establishment. What isn’t clear is the extent to which people here are engaged in commercial bushmeat poaching due to a lack of alternative food sources given the effects of the civil war.

What is the condition of the rangelands in the national parks and corridor areas?

The habitat, currently, is intact across the 200,000 sq km Boma-Jonglei ecosystem. However, there is extensive burning of habitat nearly everywhere we travelled. This is associated with the cultural tradition of using fire as a rangeland management tool to improve pasture for livestock. It isn’t clear what role the extensive burning plays on the ecology of the ecosystem. It is possible that, on the one hand, this burning could be a factor in driving migration patterns of wild ungulates by providing them with highly palatable grasses, whilst it could also be threatening overall species diversity.

How much pressure is there from local livestock?

There is a large scale pastoralist movement into parts of the ecosystem during the dry season. There is clear pressure around watering points in Boma and Bandingilo, which we presume could accentuate conflict and hunting during the dry season.

What are the barriers to setting up a viable safari circuit that might support conservation in the area?

There is no tourism infrastructure in the parks, and indeed very little accommodation in South Sudan as a whole. Access to these wild places is very challenging, given the absence of road infrastructure. Furthermore, sporadic and unpredictable conflicts, together with the proliferation of arms, mean that travel needs careful planning and local knowledge. All of that said, there is very little evidence to suggest that visitors to South Sudan have been targeted during all the years of conflict. I was pleasantly surprised by the warmth of the welcome we received from local people. Any tourism initiative would have to begin with an air-based travel solution which could be possible and very rewarding for intrepid travellers. Putting in place a simple and effective tourism visa system would also help.

What’s needed next?

Space for Giants recommends that the government works with conservation partners to undertake an immediate aerial survey of South Sudan’s national parks to establish the distribution and density of wildlife populations and identify key conservation priorities. That should include provisions for specialist survey methodologies for rhinos if credible intelligence networks can identify suitable survey areas. It should also include identifying the full extent of the area required by the white-eared kob and associated species for their annual migration and prioritise their protection through an expanded protected area system. South Sudan could submit to the United Nations for designation as a World Heritage Site and “wonder of the world”.

Through the Ministry of Conservation and Tourism, the Sudanese Government could also convene a summit of conservation NGOs and associated partners in Juba to agree on a road map for national park protection, expansion, ongoing management, and development. Based on our expertise advising national governments elsewhere, primarily in Uganda, Gabon, Kenya and now Mozambique, Space for Giants would suggest South Sudan put in place co-management agreements with reputable conservation NGOs to resource wildlife security, park infrastructure and management. In partnership with regional mobile tourism operators, South Sudan could then launch expeditionary tourism to visit its unique offerings to global tourism, including birding, sports fishing, cultural heritage, and the kob migration, to build the country’s brand as a wilderness destination.![]()

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()