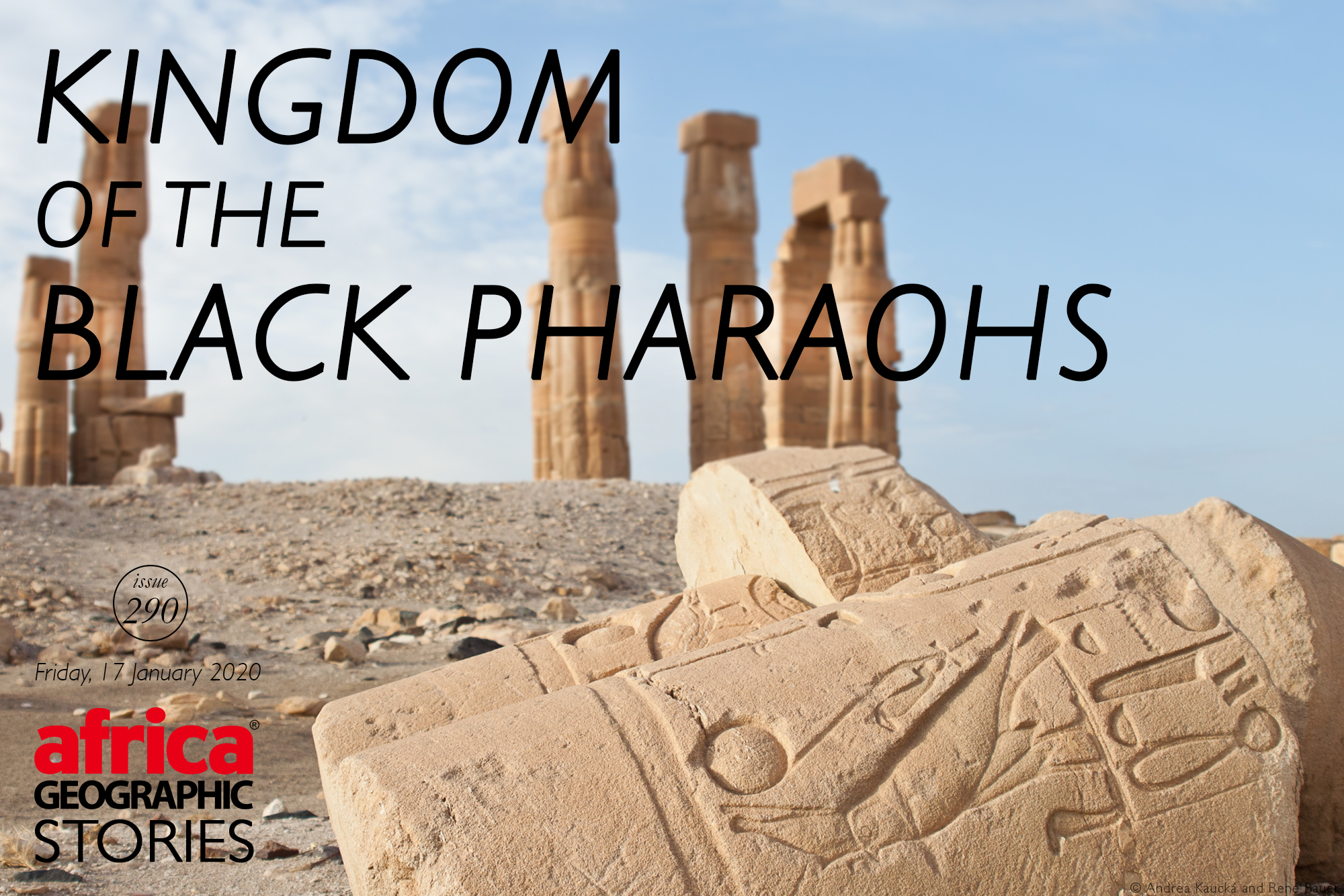

Braving Sudan's Nubian Desert to discover hidden mysteries

When we mention Sudan, most people don’t react positively, either because they don’t know much about the country, or they recall negative news reports about it. Ten years ago, when we visited the “kingdom of the black pharaohs” for the first time, there were very few tourists. Nowadays, fortunately, some prejudices have disappeared, and more foreigners (khwadja) have started visiting this northeastern African country.

Though most tourists tend to stay close to Khartoum and stick to the main routes, to visit the impressive Nubian pyramids at Meroë and remnants of ancient temples. There is so much more to discover in the country of the black pharaohs, so many more archaeological sites that tell stories from ancient times.

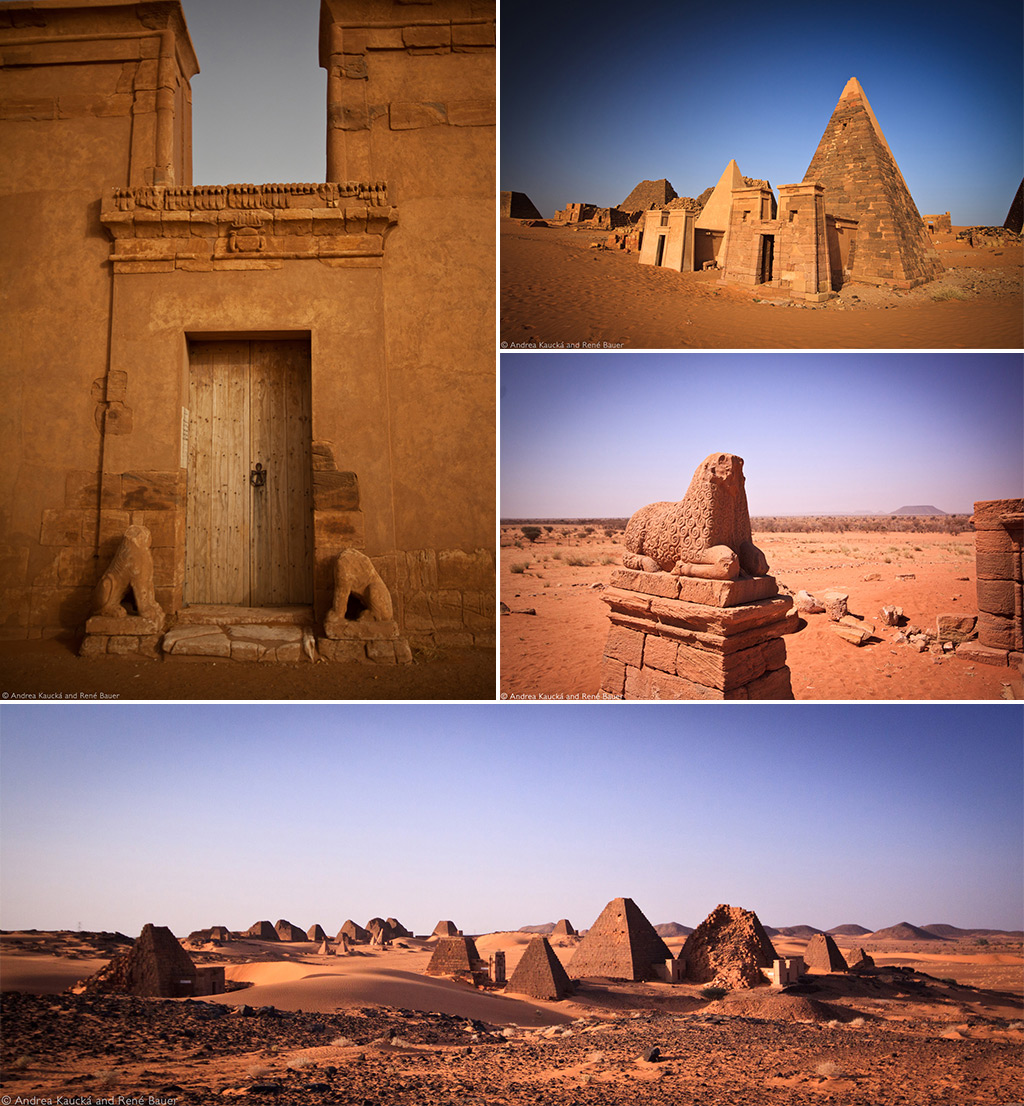

? Sudan boasts many temples and ancient remnants – the most famous being the Nubian pyramids at Meroë © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

The ‘tourist boom’ started in about 2012 when several archaeological societies began working in various locations to uncover treasures of long-forgotten civilisations. Every year we returned to Sudan on expeditions that zigzagged across the barren countryside, and every year we discovered new and interesting places.

? Left) The prayer hall at Khatmiyah Mosque in Kassala; Right) The pyramids at Meroë were built by the rulers of the ancient Kushite kingdoms that are known as the ‘black pharaohs’ © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

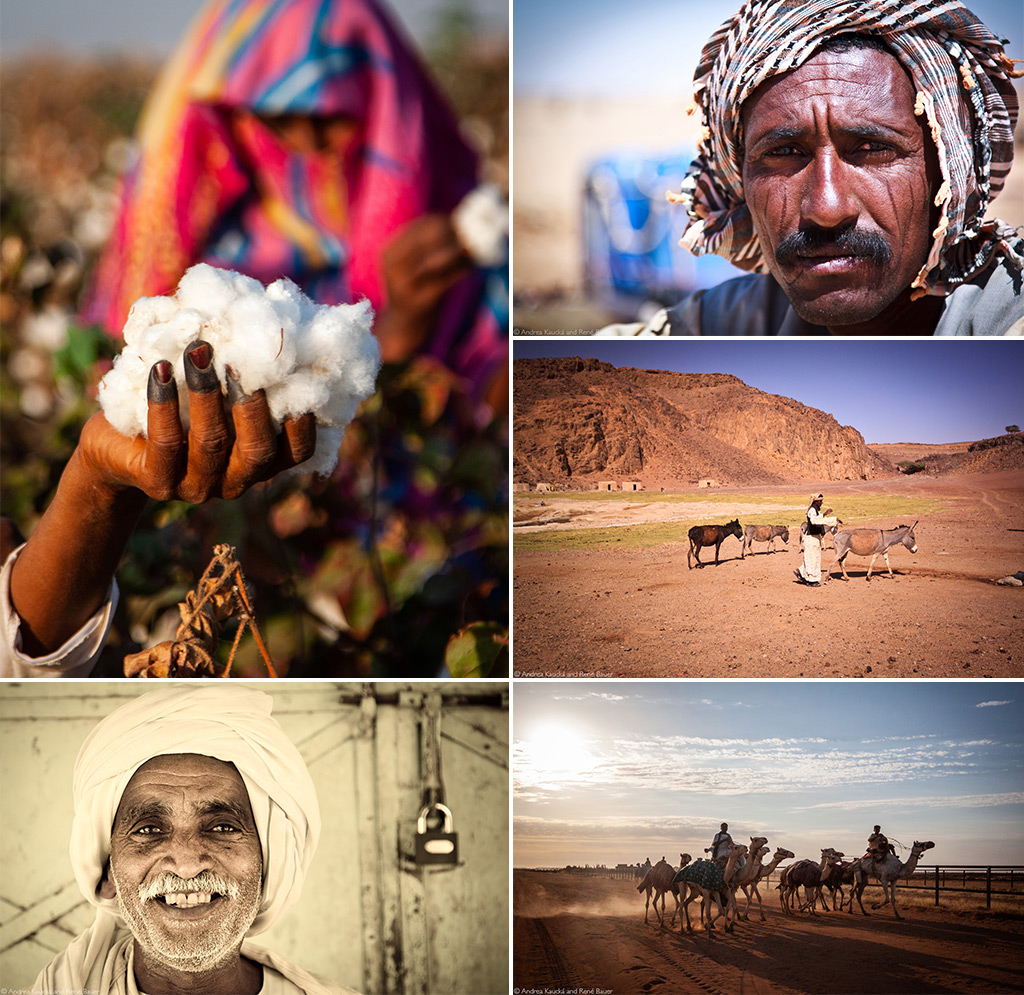

? A nomad woman in Kassala, Sudan © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

ASK UNCLE GOOGLE

It was during one particular trip to Sudan that we found ourselves deep within the desolate Nubian Desert, on a quest to find an intriguing-looking rock with an even more interesting name: Jebel Magardi.

Our adventure started when we came across a large poster of this rock in the national museum in Khartoum. We questioned all of our Sudanese friends and their friends to help us find this mysterious Jebel Magardi in an area called Bir Nurayet – the massive rock no one had ever heard about. We ended up spending hours on Google Earth searching for the mysterious rock in the middle of the Nubian Desert and eventually pinpointed an approximate location close to the Egyptian border, deep in the desert.

? Clockwise from left: 1) Camping in the Nubian Desert; 2) Roughly 1 000 km of off-road driving was a fun experience; 3) Climbing to the top of the dunes provided some great landscape shots of the Nubian Desert; 4) Another beautiful desert camp, in the middle of nowhere and not a hint of civilisation. All images © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

We created a waypoint and started looking into how to get there and decided to approach the desert from the Red Sea coast so that we could find a lonely beach to rest up before the strenuous journey. We picked out routes that went through wadis (dry riverbeds), as this seemed like the easiest way through the Red Sea mountain range. In the comfort of our home, it only took us a few hours to find a route on the computer, but of course, the reality was somewhat different.

? Clockwise from top left: 1) A temple with lion statues at Musawarat – dedicated to Apedemak – a lion-headed warrior god; 2) Sudanese pyramids are smaller than their Egyptian cousins; 3) Statue of a ram. The ram is attributed to Amun, the god of the air; 4) The pyramids at Meroë are smaller than their Egyptian counterparts and were built between 2,700 and 2,300 years ago © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

MESSAGES FROM THE END OF THE WORLD

With our three off-road vehicles loaded up, we travelled from Khartoum to Port Sudan, and north towards the Egyptian border. In Mohammed Qol, they already knew who we were, because in the previous year we had been arrested at the police checkpoint. The officers had no idea what a tourist was and why we would want to explore Sudan and instead believed us to be CIA spies. Looking back, this misunderstanding was actually quite amusing…

? “We love the desert; one feels free there. For those who respect it, the desert is rewarding, but those who ignore its rules could face fatal consequences.” © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

About 50 km behind Mohammed Qol, we found a remote and quiet spot by the beach and made camp. There was no phone signal and, as we set off the next day, our careful planning was all we had to rely on to get us to our destination. Heading towards a towering mountain range in the distance, we followed a wadi of deep sand that wound its way into the mountains. What a mighty river this wadi must once have been!

We passed rocks of all different shapes and colours and now and then came across small villages along the route. Green acacias dotted along the wadi helped to break up the bleak-looking landscape of sand and rocks.

There were times when we were faced with a fork in the road, and I had to double-check the GPS and radio René (who was driving the lead vehicle) to discuss which route to take. Sometimes we took the wrong turn, ending up in a dead-end, and had to backtrack. On other occasions, we got hopelessly stuck in the deep hot sand, and the whole team had to dig and push – back-breaking work.

? Left) Beja tribesman with his camel; Right) Reaching an oasis in the desert. Both images © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

SUDAN’S GOLDEN VEINS

Travelling over the golden sands of the Nubian Desert, we felt like explorers of decades long past. Sometimes we met people along the way – mostly nomadic Beja – and the way they looked at us made us think that we must have looked like aliens to them.

Often we would take a break to take photos or because our Sudanese drivers had to pray. And it is was then that the emptiness of the landscape hit home. We would stand in awe, listening to the quiet around us. We could hear the wind blowing through the wadi and felt it on our skin, the sands slightly shifting below our feet. The ‘nothingness’ was broken only by the odd acacia tree, small village or occasional goat or camel.

We were seven hours into our adventure and had only covered a mere 150 km. On Google Earth, it didn’t look that far, but then we were spending quite a bit of our time stopping for photos because there was something worth photographing around almost every corner.

? The people of the desert, clockwise from top left: 1) A cotton picker; 2) A nomad with facial scarring; 3) A nomad tends to his donkeys; 4) In areas not conducive to farming, people (many of them nomads) support themselves by raising cattle, sheep, goats, or camels; 5) “The locals welcomed us with a smile”. All images © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

Finally, we reached Wadi Oko, the biggest wadi in the area. There was more traffic here, and a gold diggers town! Our Sudanese drivers were not too happy about it, but the locals welcomed us with a smile and even pulled out their smartphones to take selfies with us.

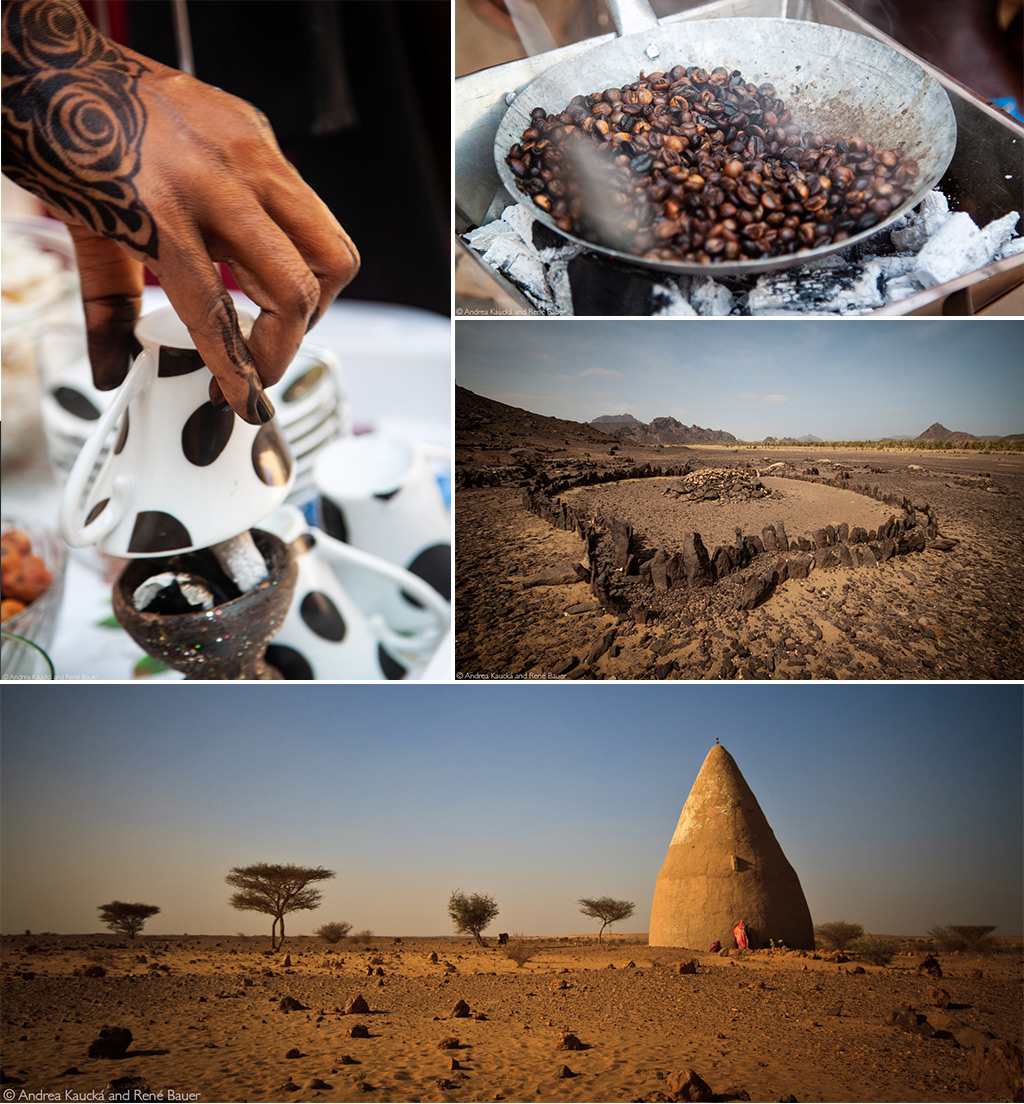

It was scorching, so we stopped for lunch and of course jebenah – a fantastic Sudanese coffee prepared in a specially-designed flask.

? Drawing water from a well at a gold mine © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

There are many more of these gold digger towns in the Nubian Desert and the Red Sea Hills. This is no huge surprise, considering that Nubia was the primary source of gold for ancient Egyptians. Descriptions of the precious metal appeared in hieroglyphs as early as 2600 B.C., and by 1500 B.C. gold had become the recognised medium of exchange for international trade. Pharaohs sent expeditions to Nubia to mine the quartz lodes for gold, which Egyptian goldsmiths transformed into vessels, furniture, funerary equipment and sophisticated jewellery. Even the name Nubia is considered by some to be a derivative of the Egyptian word for ‘gold’.

? Clockwise from top left: 1) Jebenah, Sudanese coffee, being prepared; 2) Freshly roasted coffee; 3) An ancient gravesite along the way to Bir Nurayet; 4) A qubba is an Arabic term for tomb structures, particularly Islamic domed shrines. These tombs were dotted along the way en route to Bir Nurayet. All images © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

LOST IN THE DESERT

Moving on from the gold-digging towns we found ourselves off-roading for about two hours when suddenly a green valley opened up before us, and as the sun started to dip below the horizon the golden light illuminated a majestic rock rising out of the valley ahead of us – Jebel Magardi! From afar, the rock looked like the head of a moray eel coming out of the ground, but in an archaeological context, Jebel Magardi represents a phallus symbol, an ancient sign of fertility. In its shadow, we found an area that the locals call Bir Nurayet to make camp.

It was quite late by the time we had set up camp. We sat around the crackling campfire and celebrated – not only because we had found Jebel Magardi, but also because it was René’s birthday. What better celebration could one wish for than sitting deep in the desert with absolutely no civilisation around us? It was just us and the desert that night.

? Left) Jebel Magardi and the contrasting cracked earth of the Nubian desert; Right) Camping at Bir Nurayet. Both images © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

The Sahara is a seemingly barren sea of hot sand, and yet a mere 13,000 years ago it was a thriving, lush landscape teeming with life. Wildlife such as giraffe, various antelope, elephant, ostrich and (later on) cattle once roamed this area, along with human hunter-gatherers. It is hard to believe what the desert once was, but thankfully there is evidence left behind by the ancient inhabitants, in the form of petroglyphs (rock paintings) of their life and the wildlife they encountered.

These petroglyphs are found in one of the biggest rock art galleries in the world. Discovered in 1999 by the Polish archaeologist Pluskot and his Dutch writer and photographer Baaijens during their camel caravan expedition, these petroglyphs depict scenes such as ancient hunts and cattle herding practices – lively proof of how the locals lived thousands of years ago.

? Jebel Magardi, a massive monolith, rises out of the desert and towers above Bir Nurayet © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

At sunrise, we used the golden hour to walk around Jebel Magardi, looking for these petroglyphs. The rock looked even more majestic when we stood at its base, and we wondered what it would tell us if only it could speak. In times of the old caravans and bushmen, Jebel Magardi was used as an orientation point in the desert, easy to see from far away and with a wellpoint next to it.

But even after walking all around the rock we couldn’t find any petroglyphs. Just nothing. Where were the petroglyphs? Opposite the rock there was a dry riverbed and behind were a few rocks and cliffs, one of which looked like a camel head… and something told us we should go over to investigate.

SURROUNDED BY ELEPHANTS

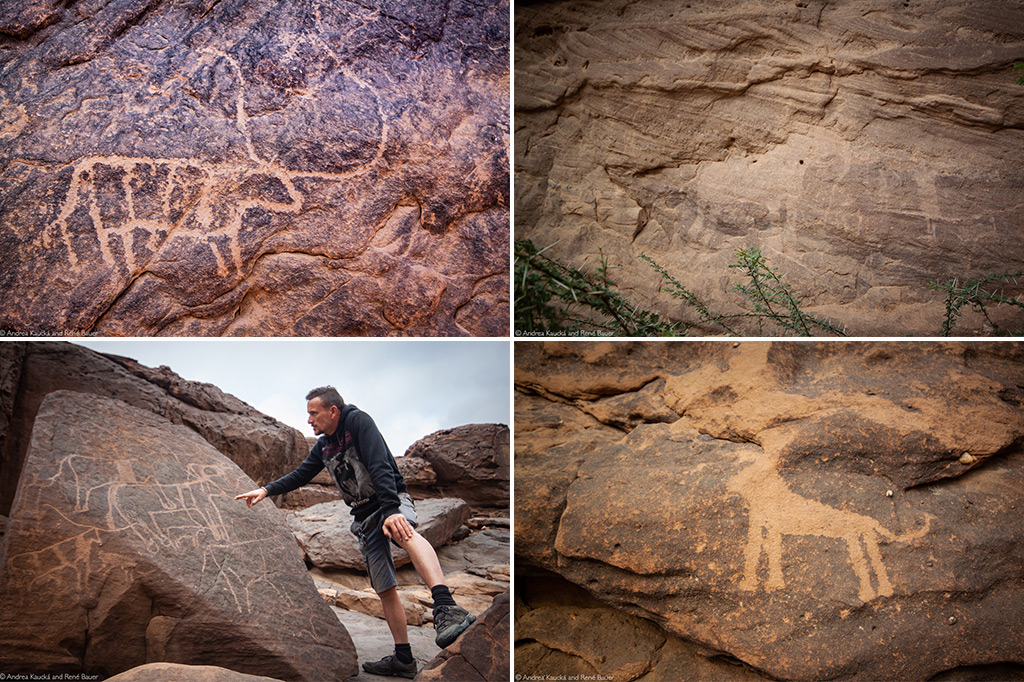

We entered a little valley in between the rocks and on every rock face there were drawings of hundreds of cattle, all with very long horns, side by side with herds of camels and humans. We made our way past all these rocks paintings, utterly fascinated. In between these petroglyphs, we found a scene of an antelope hunt, then, a few metres further, elephants walking along, and even further down, we recognised a leopard.

? Pastoralists using petroglyphs of longhorn cattle to communicate the ancient tradition of raising cattle © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

One can see what animals lived in this area when humans settled here for the first time. Some petroglyphs were very simple; others were very intricately engraved – a good sign of the progress of human art.

The art of Bir Nurayet is attributed to the Neolithic period and mostly depicts a fertility cult. We explored, discussed and imagined the stories for each drawing we saw. In the national museum in Khartoum, one can see 63 little statues and clay pots found at Bir Nurayet.

? Various petroglyphs found at Bir Nurayet, clockwise from top left: 1) Longhorn cattle; 2) Evidence that elephants once roamed the area; 3) A depiction of what is suspected to be a lion; 4) René getting a closer look at the ancient petroglyphs. All images © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

We were fascinated and happy to have found a place deep in the desert, which only a handful of people know of and have visited. We had accomplished our mission to see Jebel Magardi and its petroglyphs! Our state of delight made the two-day return journey to Khartoum a breeze, as we left ‘our’ discovery of the ancient hidden riches of Sudan’s Nubian Desert behind.![]()

? The main subject matters of the various petroglyphs at Bir Nurayet are longhorn cattle, camels, wild animals, and shepherds, hunters and battle scenes © Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS, Andrea Kaucká and René Bauer

Andrea and René met in New Zealand in 2005. Since then they have worked and travelled in various places in Europe. Their biggest adventure was crossing Africa from north to south in their vehicle in 2008/2009. During this trip, they travelled through Sudan and knew that it wouldn’t be the last time. They return to Sudan every year to discover more places, especially in the Nubian Desert. They are both tour guides, conducting trips in Europe and Africa, and write regularly for magazines, as well as hold photo exhibitions and slideshow presentations.

Andrea and René met in New Zealand in 2005. Since then they have worked and travelled in various places in Europe. Their biggest adventure was crossing Africa from north to south in their vehicle in 2008/2009. During this trip, they travelled through Sudan and knew that it wouldn’t be the last time. They return to Sudan every year to discover more places, especially in the Nubian Desert. They are both tour guides, conducting trips in Europe and Africa, and write regularly for magazines, as well as hold photo exhibitions and slideshow presentations.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()