The tiny killifish lives in a state of suspended animation – until seasonal rains trigger the shortest known lifespan of any animal with a backbone. This rapid lifecycle has scientists scrambling to unlock secrets to our own ageing processes.

The turquoise killifish (Nothobranchius furzeri) lives in temporary pools of water in some semi-arid regions of Mozambique and Zimbabwe, and, when the water dries up, the adult fish die and their drought-resistant eggs and embryos are entombed in hard mud where they enter a state of suspended animation (diapause) until the next rainfall event – months or years away.

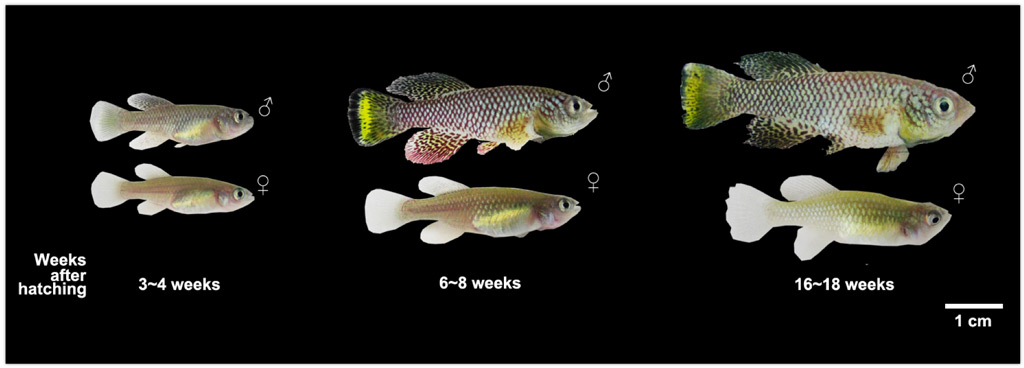

The arrival of precious rains triggers a frenetic race against time to hatch, grow to sexual maturity, mate and lay the next generation of eggs before their puddle dries up. After hatching, the turquoise killifish only lives for about nine to ten weeks in the wild before succumbing when the water dries up and has the dubious distinction of reaching sexual maturity sooner than any other vertebrate species – at about 14 days.

Studies of captive turquoise killifish and a related species, Nothobranchius kadleci, show that their body length increases by up to a quarter every day in their first two weeks of life.

Killifish are predators, eating small crustaceans and aquatic insect larvae that co-exist in the same temporary pools of water. Captive juvenile killifish have been known to cannibalise on smaller killifish, but this has not been recorded in the wild.

Males are more colourful than females, with some species reflecting colour morphs (red and yellow morphs in the case of N. furzeri). Populations of wild killifish are female-biased, with the ratios increasing towards the end of the life cycle. Ratios of N. furzeri have been recorded as increasing from 1:2,7 at the beginning of the breeding season to 1:4,7 later in the season. The reason for the sex-bias is presumed to be that more males die due to their brighter colouration attracting a higher predation rate as well as aggressive competition amongst males for access to females.

The ways in which killifish disperse are unknown, but scientists assume that the fish are swept from their natal pools during flooding to settle into new pools and that eggs are transported between pools on the skin of large herbivores that drink and mud bath there. In his story about Gonarezhou National Park in Zimbabwe, Africa Geographic CEO Simon Espley described how it is possible that eggs are carried upstream by elephants, and that the reduction of elephant populations and restriction of their historical migration routes could conceivably impact on some killifish populations. Dario Valenzano, co-author of the attached report agrees: “I strongly believe that lack, presence, diversity and in general density of large herbivores can be key to killifish survival as a species.”

The killifishes reveal how animals can adapt to extreme environments by evolving extreme lifespans. Research on captive populations of killifish focuses on unlocking the secrets about growing old and, specifically, how to hold back the ageing process.

Full report: From the bush to the bench: the annual Nothobranchius fishes as a new model system in biology. Alessandro Cellerino, Dario R. Valenzano and Martin Reichard. Wiley Online Library.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()