WHY THE HUNTING CONVERSATION HURTS CONSERVATION

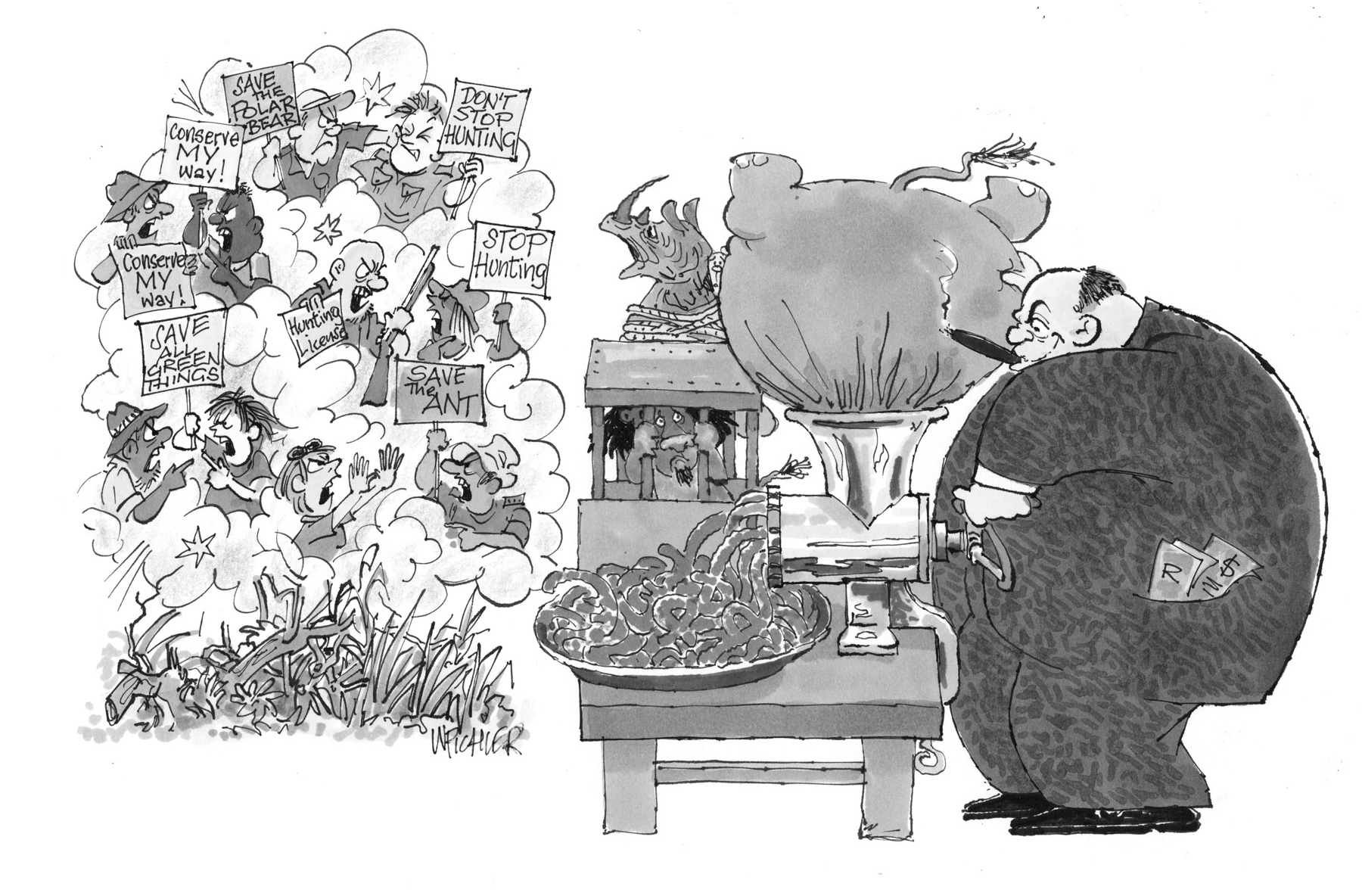

The thing about hunting is that the topic is so polarising that it prevents meaningful discourse between people who probably have more in common than they care to admit. And, while the protagonists battle it out, the grim reapers continue to harvest Africa’s wildlife and other natural resources.

We humans tend to silo information to suit our personal requirements and make enemies out of those who feel differently. We might agree on 99% of things, but the 1% apparently makes us enemies.

Let’s face it, we either hate Kendall Jones or we adore her – there is no middle ground. So the chatter around her tends to be angry, emotional, defensive and meaningless in the greater scheme of things – which is of course what she wants: the more attention she can generate the higher she ranks in the race for social media fame. And while we are distracted by her, the process of turning Africa’s incredible biodiversity into trophies, trinkets, medicine and lifestyle products continues apace. The enemies of conservation are well-resourced, focussed and not distracted by the chatter about who has the moral high ground.

I find myself discussing hunting with people from all walks of life. I make a point of speaking to hunters to try and understand their motivation. In my experience, people are mostly either rabidly for or against hunting – on ideological grounds. This rabid focus results in an inability to see facts or opinions that are not directly in the line of sight, and this kills the opportunity to learn from each other and work together towards a common goal.

Many NGOs that tend towards emotional campaigns and demand-side strategies to solicit donor funding are from the “developed” world. In contrast, many more practical approaches and supply-side campaigns come from within Africa. While some “developed” world protagonists call for tourism boycotts on African countries that offer trophy hunting, they tend to ignore the fact that it’s largely their fellow countrymen who are doing the hunting and that damaging the tourism industry via boycotts will remove livelihoods, reduce protected areas and drive more people and resources into hunting. Try explaining that to a rabid anti-hunting campaigner.

Tourism boycotts on countries that offer trophy hunting cause more harm than good

I find the act of killing animals for pleasure or ego unconscionable, and it’s sad that many trophy hunters resort to the default argument that killing animals is good for conservation. There are indeed examples where community-based hunting programs in remote unfenced areas that are not suitable for tourism do provide meaningful funding for communities and, ironically, lead to the recovery of the targeted species. Namibia has a few such examples, but this is by no means the norm. And many trophy hunters get upset when it is suggested that these examples are few and far between and that the overall picture is not as pretty as they portray.

One of the problems with hunting as a topic is that people are, by and large lazy, so little research is done outside of a narrow range of personal interests. And yet hunting is a complex topic that requires research. There are so many types of hunting, and each has its own set of implications. Examples include subsistence hunting by communities on their land, hunting on fenced private farms that choose wildlife over livestock, canned hunting and trophy hunting in unfenced areas near national parks. And there are moral/ethical considerations to weigh with the conservation implications. In my view, you shouldn’t lump all hunting debate into one pot and stir; instead, you should try to understand each situation and then debate based on its merits. In that way, you avoid generalising and insulting large groups of people (on both sides of the debate).

I was recently asked to attend the preview of a rhino horn pro-trade documentary film and to provide constructive feedback. The documentary was put together by a group of experienced, respected people (some of whom I know personally and have great respect for), and I was one of an audience of about 50. The documentary makes a passionate plea for CITES to permit the trade in rhino horn – and some of the content is compelling. Unfortunately, the documentary came across as one-sided, with some claims being made that were rather ambitious and others that were simply inaccurate. For example, it claimed that Kenya’s wildlife has been decimated since the ban on trophy hunting in 1977, and that hunting is, therefore, essential for the survival of African wildlife. I pointed out to those gathered that Tanzania and Mozambique have ongoing hunting industries, yet their wildlife has also been decimated. Therefore, the attempt to position hunting as the cure for poaching was disingenuous and did not cater to the situation’s complexity. I was hoping for intelligent debate, but sadly the panel of experts shied away from the issue, folding their arms and avoiding eye contact. Even the chairman tried to move me away from my question. It was awkward. I stood my ground and requested clarity on the issue. A well-known hunter who remained silent that evening subsequently described me on social media as an “animal rightest” – I think he meant it as an insult. And therein lies the problem – when intelligent probing questions result in insults, censorship and cessation of discussions, what chance does conservation stand?

TeamAG has to deal with ongoing attacks from people on both sides of the hunting debate – alternatively describing us as ‘bunny-huggers’ or ‘right-wing hunting promoters’, depending on the nature of the content on that day. We suffer insults, profanities and even death threats. Our mission is to educate and inspire people to celebrate Africa and do good for the continent. As difficult as some of it is to stomach, we are determined to bring you content that meets that objective.

The only thing separating him and me in our respective pursuits was the act of killing

In my discussions with hunters, I find that the reasons they commonly give for pursuing their passion just don’t add up as being exclusive to hunting. They relate to being outdoors, the bush skills required, the thrill of being close to danger etc. – all of which I get in spades when I walk in remote areas and track wild animals to observe their natural behaviour. During one recent fireside discussion, a hunter called me “ignorant and stupid” for doing all that without a gun. He had no knowledge of my bushveld experience. When I suggested that the only thing separating him and me in our respective pursuits was the act of killing, he became defensive and insulting. But after a while, he admitted that it was the act of killing that gave him the ultimate rush and that my strategy of bushwalking without weapons just can’t measure up in that regard. I respect him for coming clean on that issue and suspect that it was a cathartic discussion for him – it certainly was for me.

On the other hand, in my discussions with anti-hunters, I have found that many have the same knee-jerk response and laager mentality. It seems impossible to get them to accept that there are examples where hunting does work to keep communities gainfully employed and relatively free from animal-human conflict and that sometimes the target species even recovers and grows in numbers. The anti-hunting lobby seems to rely largely on emotion to win votes, and contradicting facts seem to be an inconvenience.

Lets take on the threats as a united force and face the real enemies

It’s a complex situation, but the facts deserve to be considered. The Kruger National Park, South Africa’s flagship conservation and tourism drawcard is a classic example of the complex situation, but the facts are compelling. Afrikaner “Voortrekkers” moved into the Kruger area in the mid-1800s, utilising the wildlife to survive – there seemed to be no limit to the available wildlife. The arrival of gold prospectors also put pressure on wildlife, with active trade in horns, skin and meat, and the arrival of “sportsmen” (trophy hunters) from Europe finally resulted in the decimation of most of the wildlife by the early 1900s. The government at the time tried to implement a series of laws to regulate hunting, none of which were successful. Eventually, some game reserves were proclaimed, the beginnings of what is now the Kruger National Park (KNP). Today some private farms sharing unfenced borders with KNP – the Greater Kruger – offer hunting. Much of the Kruger wildlife can migrate into these areas, putting them at risk, but not as much risk as they face on nearby livestock and citrus farms with little tolerance for wild animals. And so the Kruger area has recovered from historical plunder, and there is an uneasy truce between hunting, tourism and conservation. There are examples of foul play, but broadly the system works, and it stands as an example of how things can progress if different groups cooperate for the common good.

My parting thought is to challenge you to get involved in the debate. Whatever your views please try to respect others and their opinions and harness your emotions to fuel your energy and not to override your common sense. Let’s take on the threats to Africa’s biodiversity and wild areas as a united force and face the real enemies.

Keep the passion.

Contributors

SIMON ESPLEY I am a proud African of the digital tribe and am honoured to be Africa Geographic’s CEO. My travels in Africa are searching for wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. I live in South Africa, with my wife, Lizz and 2 Jack Russells. When not travelling or working, I am usually on my mountain bike somewhere out there. I qualified as a chartered accountant but found my calling sharing Africa’s incredibleness with you. My motto is “Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change”.

SIMON ESPLEY I am a proud African of the digital tribe and am honoured to be Africa Geographic’s CEO. My travels in Africa are searching for wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. I live in South Africa, with my wife, Lizz and 2 Jack Russells. When not travelling or working, I am usually on my mountain bike somewhere out there. I qualified as a chartered accountant but found my calling sharing Africa’s incredibleness with you. My motto is “Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change”.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()