Human-wildlife conflict is an ever-growing threat to wildlife (and people) in Africa. Scientists from the Zambia Lion Project at the University of California examining the skulls of lions and leopards have found that simple forensic methods can improve the detection of previous non-lethal injuries from snares and shotguns.

Quantifying the extent of human-wildlife conflict is challenging for conservationists and policymakers, as many incidents go undetected and unreported. Mortality of animals is usually used to estimate its effects on wildlife, but this approach fails to include non-lethal injuries, which are difficult to detect. As a result, the potential for underestimation is high. Notably, this new research found definitive evidence of snare entanglement that greatly surpassed the previous estimates for the Luangwa and Kafue regions in Zambia. The researchers also discovered that nearly a third of the examined male lions had old shotgun-pellet injuries to their skulls.

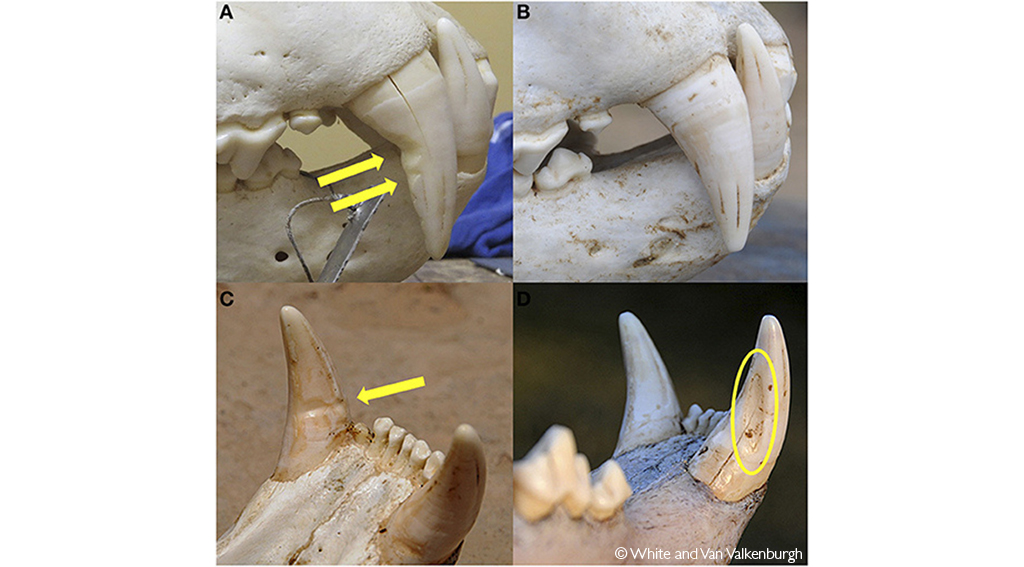

These findings came from the forensic examination of the skulls and teeth of 112 trophy-hunted lions and 45 trophy-hunted leopards that lived in Zambia between 2000 and 2012. Researchers noticed unnatural wear marks on the teeth and, by comparison with evidence from pumas, foxes and coyotes, were able to conclude that these marks were made by biting and pulling on wire snares. The grooves left behind on the teeth are distinctive and distinguishable from natural tooth wear. Snares can have a devastating effect on both individual animals and the ecology of an area due to their indiscriminate nature and capacity for severe injury and suffering. For carnivores, the impact of snares is two-fold: depleting their natural supply of prey and causing potentially lethal injuries.

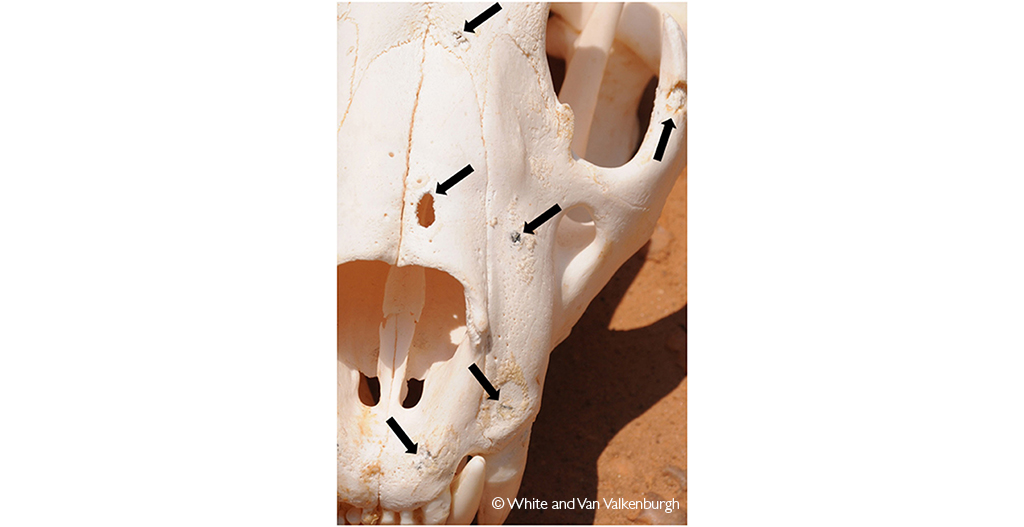

Using this method (along with other physical evidence such as characteristic scarring), the researchers found that 37% of the male lions and 22% of the leopards survived being snared and escaped during their lifetimes. Similarly, close examination of some of the skulls revealed evidence of shotgun injuries. In some cases, the pellets were still embedded in the skulls. In others, characteristic circular indentations, metal marks and bony inflammation associated with lead made these injuries easy to distinguish. 27% of the studied lion skulls had these injuries (none were found in the leopard skulls). While poachers do use shotguns, local community members may also fire shotguns to scare off carnivores without the intention of harming or killing them. However, the buckshot has the potential to cause serious injury and with the added concern of future lead poisoning.

16% of the lions from Kafue National Park and 7% from the Luangwa Valley had previously survived both snares and shotgun injuries. While it is conjecture, the researchers suggest several possible scenarios where one injury may have occasioned the other. For example, a snare injury could compromise a lion’s hunting ability, leading them to seek easier livestock prey and increasing their risk of encountering humans and being hazed with buckshot.

Interestingly, researchers concluded that the incidents of anthropogenic injuries to wild animals were higher in the Kafue region than in Luangwa. They had expected to find the opposite, as Luangwa has higher human population densities than Kafue, and poaching and human-wildlife conflict are generally more prevalent near human settlements. One possible reason is that anti-poaching and incentive programmes were more intensive and widespread in Luangwa, with an increased risk of detection due to anti-poaching programmes and higher tourist densities. However, it shows that human population size is not necessarily an accurate predictor of human-wildlife conflict, and there may be many more complex nuances.

Understanding and quantifying human-wildlife conflict is of vital importance to the survival and well-being of both Africa’s wildlife and people, as well as analysing the effectiveness of mitigation strategies. Through relatively simple forensic techniques, the authors of this new study were able to reveal more “cryptic” poaching and incidents of conflict between people and animals. They recommend that standardised photographs of the skulls and teeth of all live-captured or hunted carnivores be taken as a matter of course to aid scientific investigations.

Resources

The full study can be accessed at: White, PA., Van Valkenburgh, B., (2022) “Low-Cost Forensics Reveal High Rates of Non-lethal Snaring and Shotgun Injuries in Zambia’s Large Carnivores“, Frontiers in Conservation Science, 3.455

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()