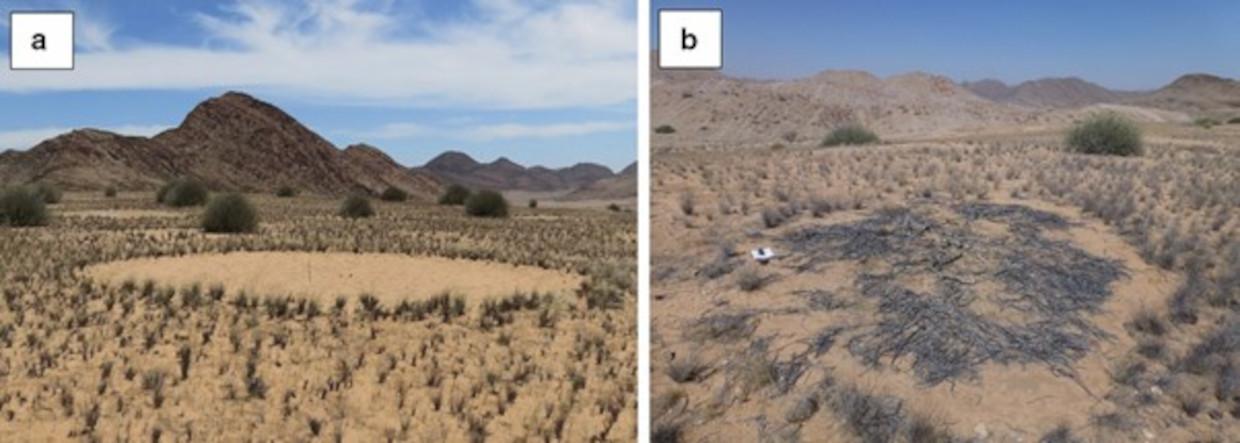

Across the deserts of Namibia and the Northern Cape in South Africa, certain areas are dotted with barren sand patches where nothing seems to grow. These peculiar ‘fairy circles’ have captured the imaginations of scientists and tourists with everything, from termites to UFOs, being mooted as potential causes. A new study from the University of Pretoria, South Africa and ITMO University in Russia indicates that dead Euphorbia plants are the culprits for the famous circles. Or, more accurately, the long-term effects of these toxic succulents on soil properties and chemistry.

The multidisciplinary study began six years ago with researchers investigating the impact of Euphorbia species on the circles’ soil properties. They examined the effects on soil chemistry, germination inhibition and antimicrobial activity on rhizosphere bacteria (which many plants need to ‘fix’ nitrogen in a usable form). The researchers then compared the spatial patterns of the fairy circles with the current growth patterns of Euphorbia species, including E. damarana, E. gummifera and even E. gregaria. All of these roundish succulents contain a highly poisonous, latex-like sap.

The scientists propose that the Euphorbia species colonised the sandy soils when climatic conditions were more favourable. Research indicates that Namibia has experienced periods of significant temperature increase over the past few centuries. In the last three decades, temperatures have increased roughly three times more than the global mean. These high temperatures and increasingly arid conditions would have seen the Euphorbias competing for access to water and nutrients, particularly in soils with a low water-holding capacity. As a result, many would have died.

However, the researchers theorise that while the plants may have died off, their legacies remained deep within the soils. As the dead plants decomposed, the sticky, toxic latex would have soaked into the soils and changed its chemical properties, making it more hydrophobic (repelling water). Other compounds capable of inhibiting plant growth and microbial activity would have entered the soil, trapped around soil particles as the latex solidified. This is an example of allelopathy – where organisms produce biochemicals that inhibit the growth of other organisms.

Their theory was supported by soil analysis which revealed that soil from the fairy circles and soil taken from beneath decomposing Euphorbia plants had very similar phytochemistry (chemicals produced by plants.)

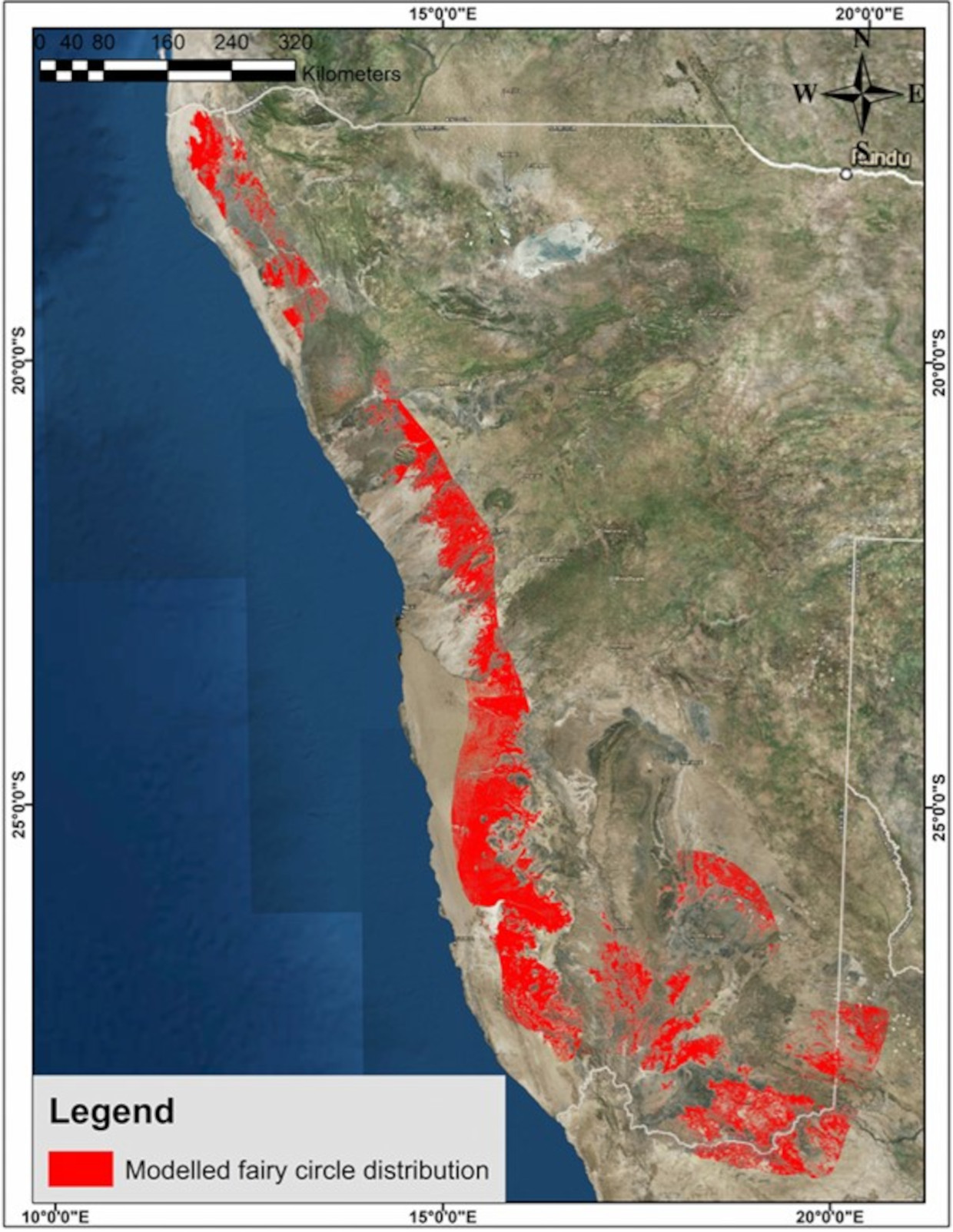

The idea that dead Euphorbias may be behind the formation of the ‘fairy circles’ has been around since the 1970s, when botanists observed the co-occurrence of the plants and fairy circles. Researchers marked dead and decaying E. damarana plants in 1978, and these circles were not covered by grasses when rechecked in 2016. By integrating rainfall, altitude and landcover into a sophisticated suitability model, the researchers in this study were also able to predict where fairy circles would be expected to occur. This model largely overlapped with the distribution of the three Euphorbia species and also resulted in the discovery of more fairy circles in the South African section of the Kalahari Desert.

However, this ‘fairy circle’ explanation has proved contentious, and there are still several scientific theories as to their origins. Sand termites (Psammotermes allocerus) were previously shown to be present in 100% of newly formed fairy circles, leading researchers to theorise that they were responsible. A recent research paper proposed that the circles are natural vegetation patterns that arose due to competition between different grass species.

For a hypothesis on the cause and maintenance of one of nature’s most mysterious phenomena to be accepted, it would have to explain all of the most important properties of the ‘fairy circles’ themselves. These include the mostly circular shape, their unusually high densities, their size and their changing diameter at different latitudes. The new study proposes an explanation of all of these characteristics, particularly given the almost circular shapes of the Euphorbia species.

If this hypothesis is correct, it also means that there is an astounding historical ‘footprint’ of hundreds of thousands of succulent Euphorbias, stretching from Angola in the north to South Africa in the south. It also explains the life-expectancy of the ‘fairy circles’ themselves. As rainfall gradually washes away the hardened latex from the soil particles, the toxins break down and allow for the natural plant succession process.![]()

The full study can be accessed here: “The allelopathic, adhesive, hydrophobic and toxic latex of Euphorbia species is the cause of fairy circles investigated at several locations in Namibia”, Marion Meyer, J. J., et al., (2021), BMC Ecology

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()