Media release from University of Pretoria

A new study from the Conservation Ecology Research Unit (CERU) at the University of Pretoria (UP) set out to unravel migration in the world’s largest terrestrial mammal: the savanna elephant.

Migration, a term often associated with wildebeest in the Serengeti, is more common amongst large mammals than one might think, particularly in species that inhabit highly seasonal environments. A common assumption is that elephants also migrate but until now there has been a lack of evidence to support this notion.

“We know elephants can move long distances and that these movements often coincide with changes in season, but whether or not these movements were migratory was hearsay,” says Professor Rudi van Aarde, supervisor of the study and Chair of CERU.

The study, published last week in Scientific Reports, set out to answer a very simple question: Do elephants migrate? It turns out the answer is a bit more complicated.

Andrew Purdon, lead author of the study explains the findings, “Elephants are a facultative partially migratory species. In other words, only some elephants migrate, and if they are migratory, they may not migrate every year.”

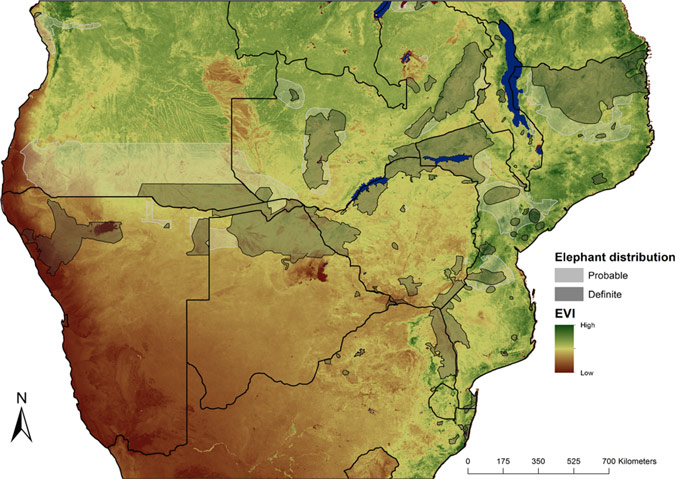

The current study, which is one of the largest studies on elephant movement to date, comprised of movement data collected over 15 years from 139 savanna elephants distributed across seven southern African countries. Of the 139 elephants, only 25 showed migratory movements – to and fro movements between two non-overlapping seasonal ranges. Of these 25 elephants, only six migrated more than once during the period they were tracked.

Although it is unclear as to exactly why these elephants migrate, the theory suggests that benefits for migratory individuals include exploiting changes in food abundance or quality, accessing spatially limited resources, or even escaping competition from other individuals.

Van Aarde elaborates, “It is plausible that during the dry season, elephants are restricted to habitats close to permanent water. At the advent of the rainy season, elephants are less restricted by water and are therefore able to move away from their dry season ranges towards areas that are greener, more productive, and that have fewer elephants.”

These results highlight the adaptive and flexible behaviour of elephants, but also their spatial needs.

Van Aarde continues, “If conditions demand it, elephants are capable of moving long distances to survive, as long as they have access to seasonal resources and the space to exploit it.”

Although few elephants migrated, most of the protected area clusters that were studied harboured migratory individuals. This included elephants in Etosha National Park (Namibia), Chobe National Park (including the Linyanti region) and Moremi Game reserve (Botswana), Hwange (Zimbabwe), Kruger National Park (South Africa), North and South Luangwa (Zambia), and the Quirimbas National Park (Mozambique). However, almost all of the migrations moved beyond National Park boundaries (IUCN category I Parks) and 11 migrations crossed international borders.

According to Michael Mole, a co-author of the paper, “The one thing these protected areas all have in common is that they are large, often buffered by secondary protected areas, and are relatively un-fragmented. Migrations need space, some of these elephants’ travel over 100 km to reach their seasonal ranges.”

“The fact that elephants are still able to move such vast distances and beyond international borders speaks wonders and points to the amazing conservation initiatives employed by many governments and organisations striving to maintain functional space and connectivity between and around national parks.”

Nowhere else is this clearer than in northern Botswana, where 15 elephants migrated. The national parks and surrounding protected areas (or Wildlife Management Areas) form a vast protected and mostly undisturbed heterogeneous landscape.

“At a time when long-distance dispersals are disappearing, this research underscores the importance of northern Botswana’s landscape to support some of the world’s longest large mammal migration,” explains co-author Dr Mike Chase, director and founder of Elephants Without Borders.

Nonetheless, the study begs the question. Are national parks big enough to adequately protect elephants?

Elephants that are moving beyond protected areas are at a higher risk of poaching and increasing human populations and habitat fragmentation are a reality threatening to isolate and fragment protected areas across Africa. So can more be done?

“We can start by gaining a better understanding of the spatial needs of large roaming species. Understanding the spatial requirements of species can help better inform the establishment of functional protected area networks,” Purdon says. “In this way, conservation areas across Africa can be large enough to effectively conserve large scale ecological processes such as migration.”

Full report: Scientific Reports, Andrew Purdon, Michael A. Mole, Michael J. Chase & Rudi J. van Aarde (2018): Partial migration in savanna elephant populations distributed across southern Africa

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()